Saturn's Coolest #2: Enceladus

Like almost all of Saturn's moons, Enceladus keeps one face toward Saturn. (I just talked yesterday about the interesting exception.) That's for good reason - the closer you are to an object, the stronger the "slope" of its gravitational pull (and Enceladus orbits very close to Saturn: second closest world after Mimas). Because the planet's gravity is getting stronger quickly as you move towards it, the front side of a moon orbiting Saturn is pulled toward Saturn harder than the back of the moon. If it started out rotating, this tidal force slowed its rotation down - and given hundreds of millions or billions of years, the rotation stops, and the moon winds up facing the same side toward its planet.

But that happens to all the moons. (Our moon keeps one face toward the Earth for the same reason.) But because Enceladus is so close to Saturn, the tides have a much more interesting effect.

What is the effect? Well, how tides work, the front of the moon, being permanently closer to Saturn, "wants" to be in a lower orbit than the back of the moon - this creates a constant pressure to pull the moon apart. And when you have constant pressure like that on a world, the world creaks and groans. The parts shift against each other, and flex back and forth. In other words, it's seismically active.

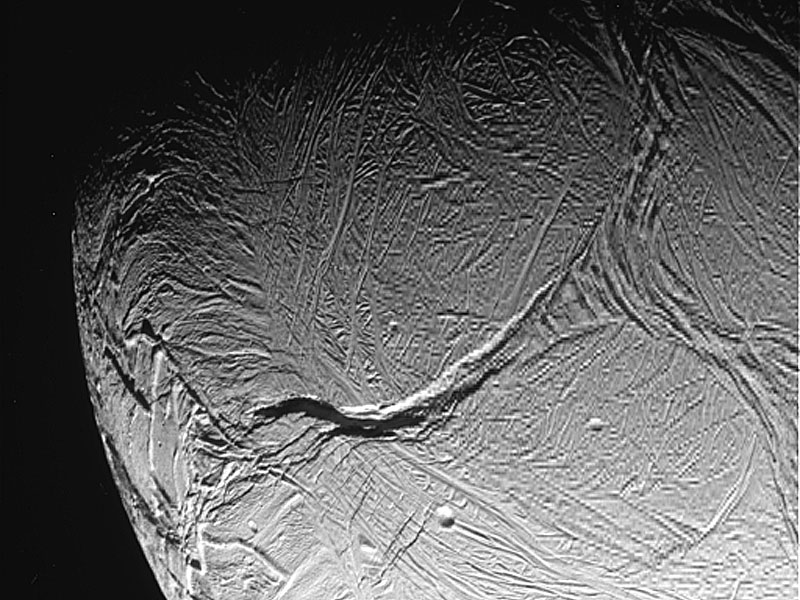

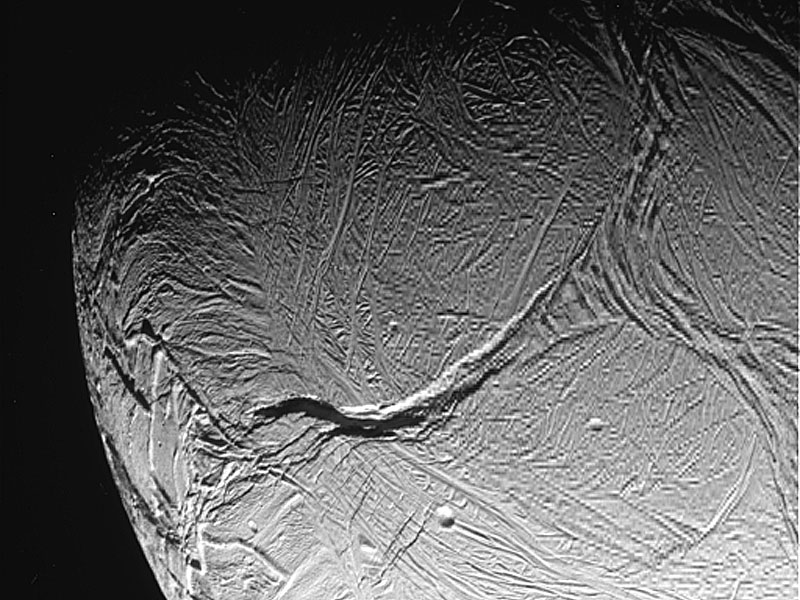

Jupiter has a dramatic example of that effect with Io - Io is covered in volcanoes and gets continually covered over by fresh lava. Seismic activity causes subsurface heat - and Enceladus, while it has some rock in its core, is largely a ball of ice. At Saturn's distance, that ice behaves just like any other rock - and this tidal flexing causes enough heat to melt the ice. Enceladus, under its surface, has a liquid water ocean - and its surface, instead of being old and cratered, is bright, cracked ice.

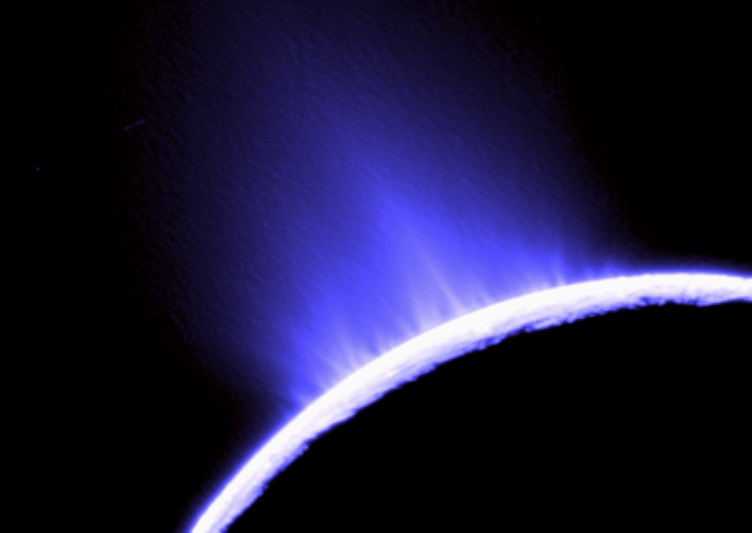

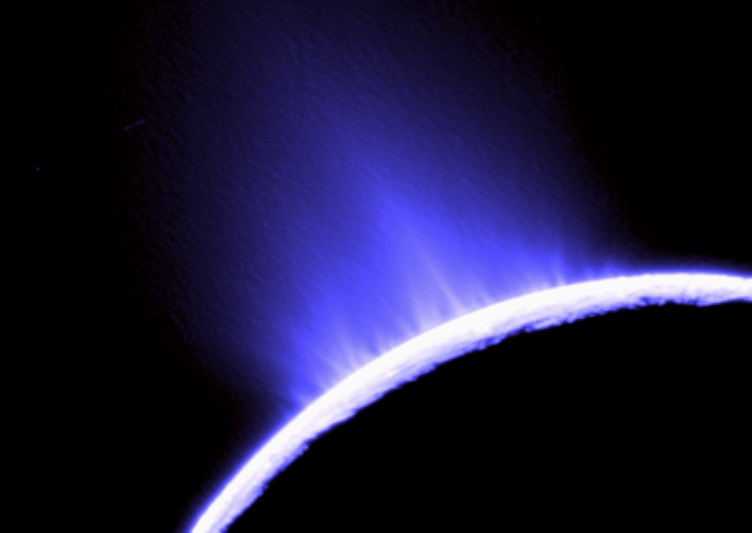

Now that part isn't unique either. Jupiter's moon Europa also has a subsurface ocean and bright surface ice, for the same reason. But Enceladus (with a 300 mile diameter) is way smaller than either Io or Europa (which are about the same size as our Moon - about 2000 miles across). Enceladus combines the effects of Io and Europa - it has a subsurface ocean, *and* volcanoes (of ice water) - in this much smaller package. And since Enceladus is so tiny and has so very little gravity, the volcanoes erupt at escape velocity. The water ice that leaves Enceladus does not come back.

So where does it go? It keeps orbiting Saturn. What do you call lots and lots of ice crystals orbiting Saturn? Rings.

Not all of them, not just from Enceladus. We do know this much for sure: while most of Saturn's rings are inside of Mimas' orbit (we talked about the F ring, between Prometheus and Pandora, at the beginning of this list, and the main rings are inside of that), there's another ring - a fat, faint, diffuse ring, that starts at Mimas' orbit and extends out past Tethys and Dione - the E ring. And from its shape and density around Enceladus' orbit, we can tell it is created by Enceladus, which has been spewing out ice crystals into Saturn's system for billions of years.

Enceladus' geysers cause the E ring. Methone - orbiting inside its densest area - gets its bizarre perfectly smooth snow blanket from Enceladus.

And this material might - we don't know, but it might - also be the source of some of the material in the main rings. Enceladus may be the other part (with pieces of what Hyperion used to be) of why Saturn is what it is. Probably not the majority of it, unless Enceladus started out a lot bigger - there's a lot of material in the rings, and the breakup of something really big explains it better, given what we know now. But we don't know the full extent of Enceladus' contribution, and I'd very much like to.

Of course, more exciting than how much the geysers contribute to Saturn's rings is the fact that Enceladus is made of liquid water. Water in liquid form is the one thing that is definitely required for biochemistry (as we understand it) to happen. We have no idea whether biochemistry happens on Enceladus (or whether it happens under the surface of the much larger Europa - or for that matter in any of the other places where liquid water exists, deep below surfaces, like Triton, and some spots on Mars, and maybe other places too.) But if you told me there was life in the Solar System other than Earth, Enceladus would be one of the first places I'd look.

So the big stories of the Saturn system all seem to gather into moons #3 and #2 on my list. Hyperion brings together the core of the mystery of the grand destruction that cratered Mimas and Tethys, strewed debris through the system, and created the rings; and Enceladus provides the snow that coats Methone and creates one of the rings - and it may have life on it.

What's left?

The most Earthlike place in the Solar System outside of Earth, that's what. See you tomorrow.

But that happens to all the moons. (Our moon keeps one face toward the Earth for the same reason.) But because Enceladus is so close to Saturn, the tides have a much more interesting effect.

What is the effect? Well, how tides work, the front of the moon, being permanently closer to Saturn, "wants" to be in a lower orbit than the back of the moon - this creates a constant pressure to pull the moon apart. And when you have constant pressure like that on a world, the world creaks and groans. The parts shift against each other, and flex back and forth. In other words, it's seismically active.

Jupiter has a dramatic example of that effect with Io - Io is covered in volcanoes and gets continually covered over by fresh lava. Seismic activity causes subsurface heat - and Enceladus, while it has some rock in its core, is largely a ball of ice. At Saturn's distance, that ice behaves just like any other rock - and this tidal flexing causes enough heat to melt the ice. Enceladus, under its surface, has a liquid water ocean - and its surface, instead of being old and cratered, is bright, cracked ice.

Now that part isn't unique either. Jupiter's moon Europa also has a subsurface ocean and bright surface ice, for the same reason. But Enceladus (with a 300 mile diameter) is way smaller than either Io or Europa (which are about the same size as our Moon - about 2000 miles across). Enceladus combines the effects of Io and Europa - it has a subsurface ocean, *and* volcanoes (of ice water) - in this much smaller package. And since Enceladus is so tiny and has so very little gravity, the volcanoes erupt at escape velocity. The water ice that leaves Enceladus does not come back.

So where does it go? It keeps orbiting Saturn. What do you call lots and lots of ice crystals orbiting Saturn? Rings.

Not all of them, not just from Enceladus. We do know this much for sure: while most of Saturn's rings are inside of Mimas' orbit (we talked about the F ring, between Prometheus and Pandora, at the beginning of this list, and the main rings are inside of that), there's another ring - a fat, faint, diffuse ring, that starts at Mimas' orbit and extends out past Tethys and Dione - the E ring. And from its shape and density around Enceladus' orbit, we can tell it is created by Enceladus, which has been spewing out ice crystals into Saturn's system for billions of years.

Enceladus' geysers cause the E ring. Methone - orbiting inside its densest area - gets its bizarre perfectly smooth snow blanket from Enceladus.

And this material might - we don't know, but it might - also be the source of some of the material in the main rings. Enceladus may be the other part (with pieces of what Hyperion used to be) of why Saturn is what it is. Probably not the majority of it, unless Enceladus started out a lot bigger - there's a lot of material in the rings, and the breakup of something really big explains it better, given what we know now. But we don't know the full extent of Enceladus' contribution, and I'd very much like to.

Of course, more exciting than how much the geysers contribute to Saturn's rings is the fact that Enceladus is made of liquid water. Water in liquid form is the one thing that is definitely required for biochemistry (as we understand it) to happen. We have no idea whether biochemistry happens on Enceladus (or whether it happens under the surface of the much larger Europa - or for that matter in any of the other places where liquid water exists, deep below surfaces, like Triton, and some spots on Mars, and maybe other places too.) But if you told me there was life in the Solar System other than Earth, Enceladus would be one of the first places I'd look.

So the big stories of the Saturn system all seem to gather into moons #3 and #2 on my list. Hyperion brings together the core of the mystery of the grand destruction that cratered Mimas and Tethys, strewed debris through the system, and created the rings; and Enceladus provides the snow that coats Methone and creates one of the rings - and it may have life on it.

What's left?

The most Earthlike place in the Solar System outside of Earth, that's what. See you tomorrow.