(no subject)

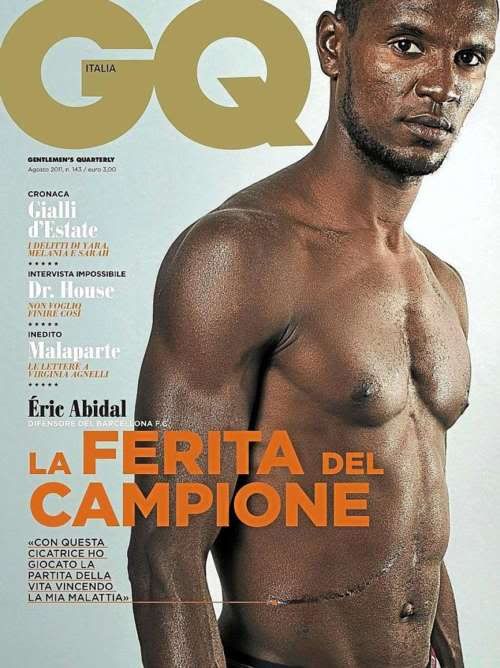

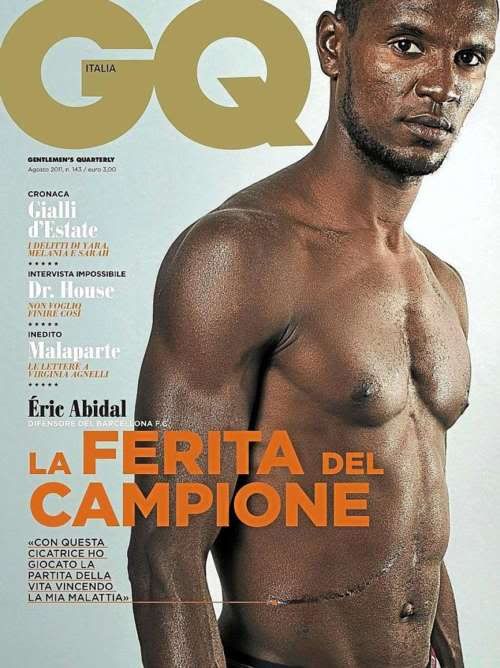

ÉRIC ABIDAL: I AM NOT AFRAID

THE SCAR OF THE WARRIOR

by Riccardo Romani, photos by Antoine Doyen shamelessly downloaded from tumblr cos my scanner sucks

translated by me

Two months ago at Wembley stadium he lifted the Champions League trophy while wearing his Barcelona shirt and the captain’s armband his teammates gave him. Two months before that, he was diagnosed with liver cancer.

This is the story of Dominique Aulanier, the incredible footballer who-should-have-been and whose dream never came true. This is the story of a moment of promised fame that was sucked back into the vortex of anonimity. Dominique was so good, pure talent. But sometimes life doesn't work itself out smoothly, destiny can change course in the blink of an eye, and you find yourself passing through a station where you thought your train would stop. Dominique Alanier waited and waited for the right train, until he became an average, common midfielder fit for a French third division team.

It was Springtime in Lyone, in the year 1999. Half the scouts in Europe were there to observe Dominique, who played for Niece at the time. Claude Puel was there, the manager of AS Monaco. He was studying the young talent like a farmer inspects cattle, trying to gauge every possible flaw.

Niece were up against Lyon-La Duchére, a fourth division team: it ended 4-0. Not in Dominique's favor. The great champion-that-should-have-been, and Puel had lost interest 13 minutes into the first half: his eye caught sight of a 19-year-old kid whose grandparents came from Martinique.

"What's his name?" he asked. He had to wait a while to get an answer. His name was Éric, Éric Abidal. In that moment in time, a metaphorical neon sign appeared, saying "Sorry Alanier, tough luck".

Éric Abidal is sitting across from me, reminiscing about that afternoon as if it were yesterday. He’s eating sliced fruit and drinking tea. Small pieces of whole wheat bread, some vegetables, then tea again. Two months ago at Wembley stadium he lifted the Champions League trophy while wearing his Barcelona shirt and the captain’s armband his teammates gave him. Two months before that, he was diagnosed with liver cancer.

It was Éric who has beg tun the interview by telling me the story of Dominique Aulanier, the would-be superstar. “It’s destiny,” he explains. “There is a divine plan that we must accept. Had I not played that game, eleven years ago, because of a cold or the flu or whatever, no one would know who I am today. I would be walking around Lyone painting walls or building parquets. When you’re nineteen you’re still dreaming about catching your big break, but you’re getting a little too old. That’s why I learned a profession, my mother had insisted upon it: she didn’t want me to be disappointed if I didn’t make it in the world of football. Everybody was there to watch Aulanier that day, and yet it was me who made it to AS Monaco the next year, in First Division. It could have been any one of my teammates who are now struggling with different jobs in Lyone. But it happened to me: today I’m famous, I play for a great club. But if you need your living room re-painted, I can come over and happily do the job for you, proudly so.”

WHY ME? On a cold Winter’s day in 2011, Éric was struck hard by the unmovable force of destiny. Cristiano Ronaldo is running in your direction and you don’t know which way you should go up against him? Something like that. Sudden thoughts rushing through your mind at super speed. “You have cancer, liver cancer. I have to operate.” The head of the Barcelona medical staff, Josep Fuster Obregon, used those precise words, like he was diagnosing him with dermatitis or something. You’re 31, in your prime physically, at the top of the world football-wise, you’re living the dream, and suddenly you have liver cancer.

“Fear. At first there was only fear,” he explains. “But then emerged the fighter in me. You’ve been fighting your whole life. To rise out of your neighborhood, to find a job, to find yourself a place within the team, to hold on to that place, to win the Champions League. This was no different. I immediately told my wife: “I’m not giving up, I’m gonna fight this. Don’t worry.” Doctor Fuster told me: “I’ll operate next week.” “No,” I told him. “No, tomorrow. First thing tomorrow. I don’t want time to think it over. Remove that tumor.”

Éric himself probably doesn’t realize what he just went through, and out of modesty he doesn’t even try to define it. A mystical experience? A voyage into the heart and spiritual core of things? A brutal rite of passage? Probably all of the above, and more besides. Since that day, everyday Éric meets people, common people, normal people: and everyone has a word of encouragement, a look of comfort to spare him. He is not only a superstar now, he is also a normal man. Éric, hospital patient. “I’ve been touring hospitals for years, with FCB, visiting the the ill, visiting orphans. It’s an obligation for us to bring a smile to people who are out of luck. For years I spoke the same words of comfort to other people that they are now telling me. In a way, I was prepared. I knew what to say, and what to do. I had to explain it to my wife. She was under an incredible pressure: she received hundreds of calls of people who wanted to know how I was but were scared of the answer. I told her to keep calm, that it would be okay. “We’ve met so many people who survived cancer and are ok”".

He also comforted a seventeen-year-old kid who shared the same room with him at the hospital. “I comforted him because it was a way to keep strong, you know. Afraid? There was no time to be afraid. You have no idea how people treated me: FCB supporters, teammates. They were fantastic. I realized that everybody has a friend, a relative or a neighbor who’s been through all of this. I learned that it’s something normal, that that’s ilfe. It can happen to anyone. No one is safe from it. I never once thought “why me”, it would have been dishonest. The day Puel came to see me play, I didn’t think “why me”: there is no difference. Life: it can take from you, and then g. Yoive back to you the next day. You just have to accept that, and give thanks every single day.”

INSHALLAH. Éric is a Muslim born to Christian parents. He converted when he reached adulthood, it was a conscious decision. Religion is really important to him: “I have read the Bible, and I have read the Quran. In the end, I chose the right path for me. My best friends in Lyone are Muslims, so it was a natural choice for me. My mother is a practicing Catholic, she goes to church every day. When I told her, she was perfectly okay with it. She told me “Éric, the important thing is that you are a good person, that you pray every day and that you remember that you only answer to God for your choices.” Nothing has changed between them, of course. “I don’t know if my religion helped me. I know that to me, faith is an advantage: knowing there’s a place we can go to after death, it helps you keep strong. It’s not a means to fight cancer, but it is a crutch. Death? I hope it’ll come when I’m much older. I had no thoughts to spare on death. To be honest, I didn’t even think I would get to play the end of the season. Not to mention the CL final!”

WEMBLEY. The world of football showed his kinder face to Abidal. When news began to circulate about his illness, there was a campaign of solidarity rarely seen before. From Totti to Beckham, from Eto’o to Rooney. Four months full of messages, whispering in the streets, hope, and finally joy, happiness. Of these four months, two things stand out to Abidal: “The love I felt during the darkest hours really surprised me. Everybody always told me I’m a nice person: those who were sincere stood by me all the way. I think I’m a good person. At work, I’m the one they come to when they need advice or help. Especially the younger teammates: they held my opinion in high regard. And so I thanked them, but in a way I knew they would be supportive. The thing that really surprised me, was the ones who should have called, visited, texted me, but didn’t. I’m not gonna name names, that person knows who they are. The first words that come to mind, are Doctor Fuster’s words: I’d just awoken from the anesthesia and he told me “My dear Éric, see you at Wembley. I’m gonna be there, and I know you’re going to be there, too.” I thought he was crazy.”

CAPTAIN. It was crazy, we were only at the quarter finals, but like Éric states, dramatic turns-of-events are always welcome. An hour before the game against Manchester United started, he didn’t know yet he was going to play. “Guardiola showed us the last videos, gave some last-minute advice, read out loud the players’ shortlist. No one looked surprised. No one but me, obviously. I sought Puyol out, I walked up to him and asked “Why aren’t you playing? Did you know he was going to leave you out?” He looked me in the eyes and said “I’m not important right now. You are what matters; don’t worry about me.” Do you have any idea what a fucking badass we have as captain? Do you? Champions League final, they tell him he’ll be warming the bench, and he’s the one comforting me! This is Barcelona. And of course I didn’t know I would be the one to lift the cup, everything happened in a blur, I could hardly grasp what was going on. Do you have any idea…? I had cancer, I had surgery, I played the CL final, and I lifted the cup, all in the span of three months. What more could I ask?”

From an outsider’s point of view, it’s hard to tell what’s gluing them all together. There is something in the basic philosophy of the Catalan club, of which Guardiola is a perfect incarnation. “The club, the team, our teammates come before everything else. We earn a lot of money, but we still train with the eagerness we had as kids. I’ve seen so many footballers who become rich and every sentence they utter begins with “I, I, me..”. Well, no one at Barça is like that. We make sure we remind each other this: it’s a game, they’re paying us to do something beautiful, let’s do it seriously but without taking each other too seriously. It’s a fact, some footballers are real snobs. It gets tiresome sometimes. I know, you want me to talk about Mourinho: he’s exasperating, but in his case, it’s all part of the strategy to reach victory. I’ve taken his side more than once in the past: this year though, to be honest, I hardly ever did.

BERLIN, 2006. Éric laughs out loud when I mention the World Cup they lost at the penalties. “You Italians are incredible… always making excuses!” he says. But I am merely using the example to introduce my next point: pain. Different kinds of pain, but pain nonetheless: facing cancer, losing a World Cup final like that, not being able to play the CL final in Rome in 2009 because of a suspension. He shakes his head. “You’re wrong. You feel no pain when you lose a World Cup, not individually anyway, because you win and you lose as a team. That is what I’ve been taught. When I got a red card against Chelsea, I lost the chance to play, but Barcelona as a team didn’t. This is important. I was sitting on the stands in Rome and I was happy. There’s nothing painful about that. When you have cancer, it’s kind of the same. It’s not a one-man game, it’s teamwork. Without the support of my family, of my supporters, of everyday people, of my fellow patients, and of my teammates of course, I wouldn’t have won against cancer.”

FAREWELL ASTON MARTIN. Manuel Estiarte, former water polo champion with Italy and today’s FC Barcelona PR manager, warned me about it: “Abi is special.” It’s true. There is no empty rhetoric in Éric’s words, he’s fighting hard against being labeled a “hero”. He’s full of humanity. And there’s that feeling that for him, something has changed forever.

“What did I learn from it all?” he smiles. “To eat. To take better care of my body. Maybe I even learned how to live. I sold my race cars, even my beloved Aston Martin: you can do better things with your money. There are lots of people who have cancer or AIDS who need it, and I try to give my part because I’m a privileged. But I do it quietly. If you give twenty Euro to a beggar on the street, it’s a private affair: between you, him, and God. No one else. Oh, and I have learned not to get too worked up. If my wife is showering me with words and my daughters keep whining at me, it’s okay. Every cloud has a silver lining, there’s something good in everything. What good can there be in cancer, you ask? If it ever happens to me again, I’ll know exactly how to behave. I see things differently now, I’ve matured. Life is full of paths and you have to follow them, accept them, and not complain about it. It’s like getting angry because you screwed up a penalty shot. Pretty stupid, right?”

Source: Vanity Fair Italia, which my beloved sister kindly purchased for me alkdjhfklajhdkfl.

THE SCAR OF THE WARRIOR

by Riccardo Romani, photos by Antoine Doyen shamelessly downloaded from tumblr cos my scanner sucks

translated by me

Two months ago at Wembley stadium he lifted the Champions League trophy while wearing his Barcelona shirt and the captain’s armband his teammates gave him. Two months before that, he was diagnosed with liver cancer.

This is the story of Dominique Aulanier, the incredible footballer who-should-have-been and whose dream never came true. This is the story of a moment of promised fame that was sucked back into the vortex of anonimity. Dominique was so good, pure talent. But sometimes life doesn't work itself out smoothly, destiny can change course in the blink of an eye, and you find yourself passing through a station where you thought your train would stop. Dominique Alanier waited and waited for the right train, until he became an average, common midfielder fit for a French third division team.

It was Springtime in Lyone, in the year 1999. Half the scouts in Europe were there to observe Dominique, who played for Niece at the time. Claude Puel was there, the manager of AS Monaco. He was studying the young talent like a farmer inspects cattle, trying to gauge every possible flaw.

Niece were up against Lyon-La Duchére, a fourth division team: it ended 4-0. Not in Dominique's favor. The great champion-that-should-have-been, and Puel had lost interest 13 minutes into the first half: his eye caught sight of a 19-year-old kid whose grandparents came from Martinique.

"What's his name?" he asked. He had to wait a while to get an answer. His name was Éric, Éric Abidal. In that moment in time, a metaphorical neon sign appeared, saying "Sorry Alanier, tough luck".

Éric Abidal is sitting across from me, reminiscing about that afternoon as if it were yesterday. He’s eating sliced fruit and drinking tea. Small pieces of whole wheat bread, some vegetables, then tea again. Two months ago at Wembley stadium he lifted the Champions League trophy while wearing his Barcelona shirt and the captain’s armband his teammates gave him. Two months before that, he was diagnosed with liver cancer.

It was Éric who has beg tun the interview by telling me the story of Dominique Aulanier, the would-be superstar. “It’s destiny,” he explains. “There is a divine plan that we must accept. Had I not played that game, eleven years ago, because of a cold or the flu or whatever, no one would know who I am today. I would be walking around Lyone painting walls or building parquets. When you’re nineteen you’re still dreaming about catching your big break, but you’re getting a little too old. That’s why I learned a profession, my mother had insisted upon it: she didn’t want me to be disappointed if I didn’t make it in the world of football. Everybody was there to watch Aulanier that day, and yet it was me who made it to AS Monaco the next year, in First Division. It could have been any one of my teammates who are now struggling with different jobs in Lyone. But it happened to me: today I’m famous, I play for a great club. But if you need your living room re-painted, I can come over and happily do the job for you, proudly so.”

WHY ME? On a cold Winter’s day in 2011, Éric was struck hard by the unmovable force of destiny. Cristiano Ronaldo is running in your direction and you don’t know which way you should go up against him? Something like that. Sudden thoughts rushing through your mind at super speed. “You have cancer, liver cancer. I have to operate.” The head of the Barcelona medical staff, Josep Fuster Obregon, used those precise words, like he was diagnosing him with dermatitis or something. You’re 31, in your prime physically, at the top of the world football-wise, you’re living the dream, and suddenly you have liver cancer.

“Fear. At first there was only fear,” he explains. “But then emerged the fighter in me. You’ve been fighting your whole life. To rise out of your neighborhood, to find a job, to find yourself a place within the team, to hold on to that place, to win the Champions League. This was no different. I immediately told my wife: “I’m not giving up, I’m gonna fight this. Don’t worry.” Doctor Fuster told me: “I’ll operate next week.” “No,” I told him. “No, tomorrow. First thing tomorrow. I don’t want time to think it over. Remove that tumor.”

Éric himself probably doesn’t realize what he just went through, and out of modesty he doesn’t even try to define it. A mystical experience? A voyage into the heart and spiritual core of things? A brutal rite of passage? Probably all of the above, and more besides. Since that day, everyday Éric meets people, common people, normal people: and everyone has a word of encouragement, a look of comfort to spare him. He is not only a superstar now, he is also a normal man. Éric, hospital patient. “I’ve been touring hospitals for years, with FCB, visiting the the ill, visiting orphans. It’s an obligation for us to bring a smile to people who are out of luck. For years I spoke the same words of comfort to other people that they are now telling me. In a way, I was prepared. I knew what to say, and what to do. I had to explain it to my wife. She was under an incredible pressure: she received hundreds of calls of people who wanted to know how I was but were scared of the answer. I told her to keep calm, that it would be okay. “We’ve met so many people who survived cancer and are ok”".

He also comforted a seventeen-year-old kid who shared the same room with him at the hospital. “I comforted him because it was a way to keep strong, you know. Afraid? There was no time to be afraid. You have no idea how people treated me: FCB supporters, teammates. They were fantastic. I realized that everybody has a friend, a relative or a neighbor who’s been through all of this. I learned that it’s something normal, that that’s ilfe. It can happen to anyone. No one is safe from it. I never once thought “why me”, it would have been dishonest. The day Puel came to see me play, I didn’t think “why me”: there is no difference. Life: it can take from you, and then g. Yoive back to you the next day. You just have to accept that, and give thanks every single day.”

INSHALLAH. Éric is a Muslim born to Christian parents. He converted when he reached adulthood, it was a conscious decision. Religion is really important to him: “I have read the Bible, and I have read the Quran. In the end, I chose the right path for me. My best friends in Lyone are Muslims, so it was a natural choice for me. My mother is a practicing Catholic, she goes to church every day. When I told her, she was perfectly okay with it. She told me “Éric, the important thing is that you are a good person, that you pray every day and that you remember that you only answer to God for your choices.” Nothing has changed between them, of course. “I don’t know if my religion helped me. I know that to me, faith is an advantage: knowing there’s a place we can go to after death, it helps you keep strong. It’s not a means to fight cancer, but it is a crutch. Death? I hope it’ll come when I’m much older. I had no thoughts to spare on death. To be honest, I didn’t even think I would get to play the end of the season. Not to mention the CL final!”

WEMBLEY. The world of football showed his kinder face to Abidal. When news began to circulate about his illness, there was a campaign of solidarity rarely seen before. From Totti to Beckham, from Eto’o to Rooney. Four months full of messages, whispering in the streets, hope, and finally joy, happiness. Of these four months, two things stand out to Abidal: “The love I felt during the darkest hours really surprised me. Everybody always told me I’m a nice person: those who were sincere stood by me all the way. I think I’m a good person. At work, I’m the one they come to when they need advice or help. Especially the younger teammates: they held my opinion in high regard. And so I thanked them, but in a way I knew they would be supportive. The thing that really surprised me, was the ones who should have called, visited, texted me, but didn’t. I’m not gonna name names, that person knows who they are. The first words that come to mind, are Doctor Fuster’s words: I’d just awoken from the anesthesia and he told me “My dear Éric, see you at Wembley. I’m gonna be there, and I know you’re going to be there, too.” I thought he was crazy.”

CAPTAIN. It was crazy, we were only at the quarter finals, but like Éric states, dramatic turns-of-events are always welcome. An hour before the game against Manchester United started, he didn’t know yet he was going to play. “Guardiola showed us the last videos, gave some last-minute advice, read out loud the players’ shortlist. No one looked surprised. No one but me, obviously. I sought Puyol out, I walked up to him and asked “Why aren’t you playing? Did you know he was going to leave you out?” He looked me in the eyes and said “I’m not important right now. You are what matters; don’t worry about me.” Do you have any idea what a fucking badass we have as captain? Do you? Champions League final, they tell him he’ll be warming the bench, and he’s the one comforting me! This is Barcelona. And of course I didn’t know I would be the one to lift the cup, everything happened in a blur, I could hardly grasp what was going on. Do you have any idea…? I had cancer, I had surgery, I played the CL final, and I lifted the cup, all in the span of three months. What more could I ask?”

From an outsider’s point of view, it’s hard to tell what’s gluing them all together. There is something in the basic philosophy of the Catalan club, of which Guardiola is a perfect incarnation. “The club, the team, our teammates come before everything else. We earn a lot of money, but we still train with the eagerness we had as kids. I’ve seen so many footballers who become rich and every sentence they utter begins with “I, I, me..”. Well, no one at Barça is like that. We make sure we remind each other this: it’s a game, they’re paying us to do something beautiful, let’s do it seriously but without taking each other too seriously. It’s a fact, some footballers are real snobs. It gets tiresome sometimes. I know, you want me to talk about Mourinho: he’s exasperating, but in his case, it’s all part of the strategy to reach victory. I’ve taken his side more than once in the past: this year though, to be honest, I hardly ever did.

BERLIN, 2006. Éric laughs out loud when I mention the World Cup they lost at the penalties. “You Italians are incredible… always making excuses!” he says. But I am merely using the example to introduce my next point: pain. Different kinds of pain, but pain nonetheless: facing cancer, losing a World Cup final like that, not being able to play the CL final in Rome in 2009 because of a suspension. He shakes his head. “You’re wrong. You feel no pain when you lose a World Cup, not individually anyway, because you win and you lose as a team. That is what I’ve been taught. When I got a red card against Chelsea, I lost the chance to play, but Barcelona as a team didn’t. This is important. I was sitting on the stands in Rome and I was happy. There’s nothing painful about that. When you have cancer, it’s kind of the same. It’s not a one-man game, it’s teamwork. Without the support of my family, of my supporters, of everyday people, of my fellow patients, and of my teammates of course, I wouldn’t have won against cancer.”

FAREWELL ASTON MARTIN. Manuel Estiarte, former water polo champion with Italy and today’s FC Barcelona PR manager, warned me about it: “Abi is special.” It’s true. There is no empty rhetoric in Éric’s words, he’s fighting hard against being labeled a “hero”. He’s full of humanity. And there’s that feeling that for him, something has changed forever.

“What did I learn from it all?” he smiles. “To eat. To take better care of my body. Maybe I even learned how to live. I sold my race cars, even my beloved Aston Martin: you can do better things with your money. There are lots of people who have cancer or AIDS who need it, and I try to give my part because I’m a privileged. But I do it quietly. If you give twenty Euro to a beggar on the street, it’s a private affair: between you, him, and God. No one else. Oh, and I have learned not to get too worked up. If my wife is showering me with words and my daughters keep whining at me, it’s okay. Every cloud has a silver lining, there’s something good in everything. What good can there be in cancer, you ask? If it ever happens to me again, I’ll know exactly how to behave. I see things differently now, I’ve matured. Life is full of paths and you have to follow them, accept them, and not complain about it. It’s like getting angry because you screwed up a penalty shot. Pretty stupid, right?”

Source: Vanity Fair Italia, which my beloved sister kindly purchased for me alkdjhfklajhdkfl.