Jacqueline Woodson (born February 12, 1963)

Jacqueline Woodson (b. 12 February 1963, in Columbus, Ohio) is an American author who writes books targeted at children and adolescents. She is best known for Miracle's Boys which won the Coretta Scott King Award in 2001 and her Newbery Honor titles After Tupac & D Foster, Feathers and Show Way. Her work is filled with strong African American themes, generally aimed at a young adult audience. She is an open lesbian with a lifelong partner and two children, a daughter named Toshi Georgianna and a son named Jackson-Leroi.

Jacqueline Amanda Woodson was born to Jack and Mary Ann Woodson on February 12, 1963. Although she was born in Columbus, Ohio she and her younger brother, who is biracial, grew up moving back and forth between South Carolina and Brooklyn, NY between 1968 and 1973 until her grandmother finally settled in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn. Her mother was not wealthy, but her grandparents were; she felt the economic differences each time she moved from one location to the other. She never felt that she truly belonged in either location, but began to define herself as "outside of the world" even before she reached her teens.

As is the case for many teens, her high school years were confusing. Although she dated a basketball player and had a clique of girls she belonged to, her sexuality was not conforming to the ideas of many of her classmates and she found herself questioning everything. Her political views were crushed when Nixon resigned and Ford was sworn in. The young writer felt that George McGovern should have been the new president, since he had lost the election to Nixon. When teachers couldn't give her acceptable answers to her questions she became a loner, sullen and looking for an outlet for her frustrations. She spent a lot of her time writing poems and songs that expressed her social and political disenchantment. Her college education includes receiving a B.A. in English from Adelphi University in 1985 and studying creative writing at New School for Social Research (now New School University).

Woodson and her partner have known each other since they were young girls. In 2006 Woodson gave birth to a daughter, Toshi Georgianna. The child is named after her godmother, Toshi Seeger, and Woodson's grandmother, Georgianna. She also has a son named Jackson-Leroi.

In addition to her writing, Woodson has also worked as a writing professor at Goddard College, Eugene Lang College, Vermont College as well as a Writer-in-residence for the National Book Foundation. She has also held positions as an editorial assistant and a drama therapist for runaway children in New York, NY.

She lives in Brooklyn, New York in a racially diverse neighborhood.[I wanted] to write about communities that were familiar to me and people that were familiar to me. I wanted to write about communities of color. I wanted to write about girls. I wanted to write about friendship and all of these things that I felt like were missing in a lot of the books that I read as a child.”

After college Woodson went to work for Kirchoff/Wohlberg, a children's packaging company. She helped to write the California standardized reading tests and caught the attention of a Liza Pulitzer-Voges, a children's book agent at the same company. Although the partnership didn't work out, it did get her first manuscript out of a drawer. She then enrolled in Bunny Gable's children's book writing class at the New School where Bebe Willoughby, an editor at Delacorte heard a reading from Last Summer with Maizon and requested the manuscript. Delacorte bought the manuscript, but Willoughby left the company before editing it and so Wendy Lamb took over and saw Woodson's first six books published.

Woodson's youth was split between South Carolina and Brooklyn. In her interview with Jennifer M. Brown she remembered, "The South was so lush and so slow-moving and so much about community. The city was thriving and fast-moving and electric. Brooklyn was so much more diverse: on the block where I grew up, there were German people, people from the Dominican Republic, people from Puerto Rico, African-Americans from the South, Caribbean-Americans, Asians."

When asked to name her literary influences in an interview with journalist Hazel Rochman, Woodson responded, "Two major writers for me are James Baldwin and Virginia Hamilton. It blew me away to find out Virginia Hamilton was a sister like me. Later, Nikki Giovanni had a similar effect on me. I feel that I learned how to write from Baldwin. He was onto some future stuff, writing about race and gender long before people were comfortable with those dialogues. He would cross class lines all over the place, and each of his characters was remarkably believable. I still pull him down from my shelf when I feel stuck."

Other early influences included Toni Morrison's The Bluest Eye and Sula, and the work of Rosa Guy as well as her high school English teacher, Mr. Miller. Louise Meriwether was also named.

Jacqueline Woodson has, in turn, influenced many other writers, including An Na, who credits her as being her first writing teacher. She also teaches teens at the National Book Foundation's summer writing camp where she co-edits the annual anthology of their combined work.

As an author, Woodson is known for the detailed physical landscapes she writes into each of her books. She places boundaries everywhere-social, economic, physical, sexual, racial-then has her characters break through both the physical and pychological boundaries to create a strong and emotional story.

She is also known for her optimism. She has said that she dislikes books that do not offer hope. She has offered the novel Sounder as and example of a 'bleak' and 'hopeless' novel. On the other hand, she enjoyed A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Even though the family was exceptionally poor, the characters experienced "moments of hope and sheer beauty". She uses this philosophy in her own writing, saying, "If you love the people you create, you can see the hope there."

As a writer she consciously writes for a younger audience. There are authors who write about adolescence or from a youths point of view, but their work is intended for adult audiences. Woodson writes about childhood and adolescence with an audience of youth in mind. In an interview on National Public Radio she said, "I'm writing about adolescents for adolescents. And I think the main difference is when you're writing to a particular age group, especially a younger age group, you're - the writing can't be as implicit. You're more in the moment. They don't have the adult experience from which to look back. So you're in the moment of being an adolescent...and the immediacy and the urgency is very much on the page, because that's what it feels like to be an adolescent. Everything is so important, so big, so traumatic. And all of that has to be in place for them."

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacqueline_WoodsonWoodson's prose is like music in this sweet, gently told story of a 14-year-old girl's awakening to the possibility of being gay. The story itself is as lovely and honest as its prose.

Staggerlee, who has given herself the name of a strong and defiant black folk hero, is the daughter of a black father and a white mother. She learned the original Staggerlee's story from a film clip of the last show her vaudevillian grandparents did before they were killed by a bomb while taking part in a civil rights demonstration.

Although she loves solitude and takes long walks with her dog, Staggerlee also longs for friends. She feels that something sets her apart from other girls; is it possible she might be gay? She's still haunted by the memory of a girl she once kissed who later betrayed her. And now, as the book opens, she thinks about the summer before, when her cousin, Trout, came to visit...

That summer, as the two girls get to know each other, Staggerlee feels sure she's found a soulmate who shares her feeling of being different. She and Trout talk about that a little--Trout tells Staggerlee that she's been sent to stay with Staggerlee's family in order to learn how to "be a lady"--and Staggerlee senses that there's a "secret and shameful" feeling growing inside both of them. Later, Staggerlee tells Trout about her disturbing memory of kissing a girl, and Trout says she's kissed a girl, too. Staggerlee speaks of reading a book in which a woman who loved another woman killed herself, and they wonder what all of that means, what it would be like.

A friend of Trout's, Rachel, has called Trout a few times during the summer, and when Staggerlee says she's thought she's Trout's girlfriend, Trout laughs and explains that when Rachel calls she tells Trout about parties she's gone to and the boys who've liked her. Not long after that, she tells Staggerlee that Rachel's arranged a date for her when she's back home, and she's agreed to go, although she doesn't know why, and they talk a bit about having to lie about their true feelings. Staggerlee tells Trout that she doesn't know if she's gay, and Trout writes "Staggerlee and Trout were here today. Maybe they will and maybe they won't be gay" in the dirt.

Summer ends and Trout leaves. Staggeree, who's become more confident, begins to find other friends, and she and Trout continue their friendship via phone. But by the end of October, Trout has stopped calling and doesn't respond to the messages Staggerlee leaves on her answering machine. Finally a letter arrives, a long and loving letter, in which Trout tells Staggerlee that she has a boyfriend, but she wants to go on being close to Staggerlee, "even if we don't have the girl thing in common any more."

Staggerlee rereads the letter often as time goes by, and she thinks about her new friends and Trout and wonders who she and Trout both really were and are. And finally she concludes that "They were both waiting. Waiting for this moment, this season, these years to pass....Who would they become?"

The House You Pass on the Way is the second novel in this genre to show a very young main character openly wonderng about his or her sexual orientation, and the first one in which that character is a girl. The first, the late John Donovan's I'll Get There. It Better Be Worth the Trip, was published by Harper and Row way back in 1969. It's focused on a friendship between two young boys, and the ending, like the ending of The House You Pass on the Way, leaves open the possibility that the kids may or may not end up being gay, and through the characters concludes that either way, it's okay. Donovan's was an appropriate conclusion for a book in 1969 about very young teens, as, I think, is the conclusion of Woodson's beautiful and subtle book nearly thirty years later. -- Nancy Garden

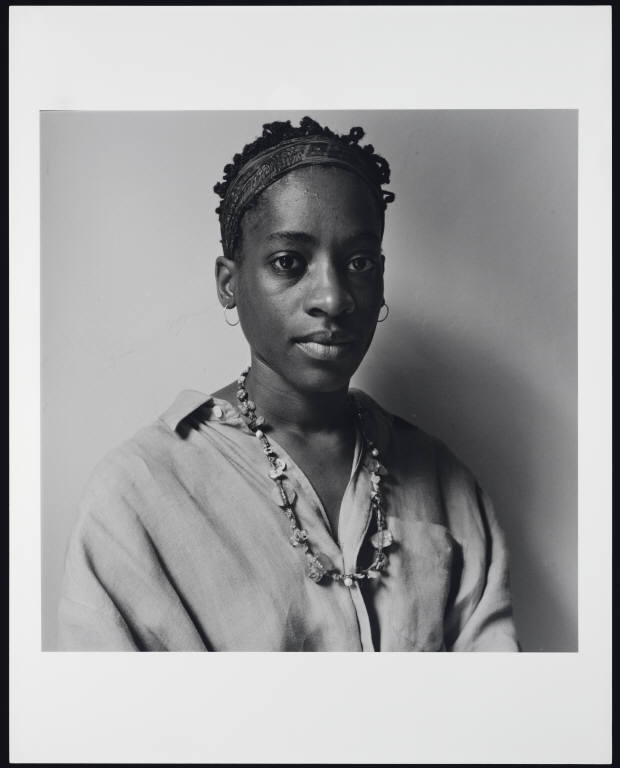

Jacqueline Woodson, 1992, by Robert Giard (http://beinecke.library.yale.edu/dl_crosscollex/brbldl_getrec.asp?fld=img&id=1125734)American photographer Robert Giard is renowned for his portraits of American poets and writers; his particular focus was on gay and lesbian writers. Some of his photographs of the American gay and lesbian literary community appear in his groundbreaking book Particular Voices: Portraits of Gay and Lesbian Writers, published by MIT Press in 1997. Giard’s stated mission was to define the literary history and cultural identity of gays and lesbians for the mainstream of American society, which perceived them as disparate, marginal individuals possessing neither. In all, he photographed more than 600 writers. (http://beinecke.library.yale.edu/digitallibrary/giard.html)

Further Readings:

From the Notebooks of Melanin Sun by Jacqueline Woodson

Age Range: 12 and up

Grade Level: 7 and up

Library Binding: 176 pages

Publisher: Turtleback (July 8, 2010)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0606145974

ISBN-13: 978-0606145978

Amazon: From the Notebooks of Melanin Sun

Amazon Kindle: From the Notebooks of Melanin Sun

Fourteen-year-old Melanin Sun's comfortable, quiet life is shattered when his mother reveals she has fallen in love with a woman.

More Particular Voices at my website: http://www.elisarolle.com/, My Ramblings/Particular Voices

This journal is friends only. This entry was originally posted at http://reviews-and-ramblings.dreamwidth.org/3446683.html. If you are not friends on this journal, Please comment there using OpenID.