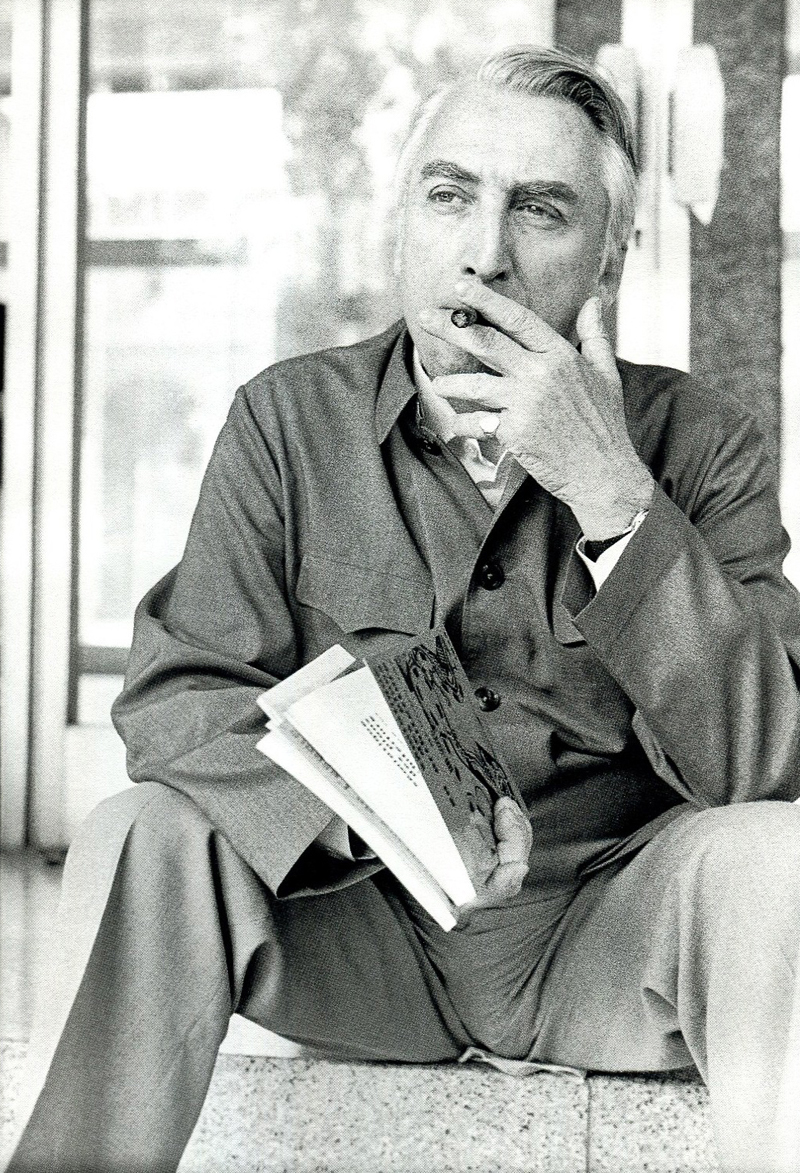

Roland Barthes (November 12, 1915 - March 25, 1980)

Like André Gide and Marcel Proust, two of his favorite writers, Roland Barthes, a semiotician many "queer theorists" find inspiring, occupied an extremely marginal position in French society. He was Protestant. (France is predominantly Catholic.) He was left-handed. (France is, of course, predominantly right-handed.) He was déclassé. (Barthes's father, a naval officer, died in the First World War, and his mother had to work as a bookbinder.) He was consumptive. (Barthes spent several years in sanatoria.) And he was expatriate. (Barthes spent the 1950s in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, working for cultural services.)

Barthes also occupied a marginal position within the French academy. Having failed to sit the agrégation exam that would have led to an orthodox career, but having already published extensively, he was forty-four when he began teaching at the École Pratique des Hautes Études, a lackluster post, and sixty when he was elected to a chair in the Collège de France, a prestigious one.

If a single factor, however, can be said to have alienated Barthes from the bourgeois culture he came to distrust and felt compelled to demystify--a deterministic approach Barthes himself rejected--it would be his "perverse" sexuality. Like Proust, if not like Gide, who saw himself as a pederast, Barthes was homosexual. And like Remembrance of Things Past, a work in which everyone except the narrator (who may or may not be named "Marcel") turns out to be gay, Barthes's critical texts--including ones that concern "text"--are best understood in relation to this sexual marginality.

Barthes preferred the notion of "text," which posits writing as open and derivative, to that of "work," which posits it as closed and sui generis. In fact, texts are so open--to playful ("ludic") interpretation and abysmal contextualization--as to be completely meaningless in any conventional sense of the word. Barthes, however, has an unconventional--and appreciative--sense of meaninglessness.

He sees meaninglessness, or "exemption from meaning," as a way of displacing conventional wisdom and dominant ideology. "What is difficult," Barthes writes, "is not to liberate sexuality according to a more or less libertarian project but to release it from meaning, including from transgression as meaning." Meaningless text, for example, displaces the conventional stereotypes (such as sexual "inversion") that pertain to gay male identity.

Because Barthes sees homosexuality, and for that matter any transgressive and eccentric "perversion," as unclassifiable, he takes the classification "inversion" to be inaccurate--a notion that will come as a surprise to gays and lesbians who see themselves as "inverts," but that, contrary to popular belief and to conventional critical wisdom, came as no surprise to Proust.

If he had to characterize--to "predicate"--gays and lesbians, Barthes might have chosen the term noninvert. Noninvert has two advantages: It is both imprecise and paradoxical. Like Oscar Wilde, whom he does not appear to have read attentively, Barthes conceives of truth as antithetical: "A Doxa (a popular opinion) is posited, intolerable; to free myself of it, I postulate a paradox; then this paradox turns bad, becomes a new concretion, itself becomes a new Doxa, and I must seek for a new paradox."

He also conceives of truth as orgasmic: "Paradox is an ecstasy, then a loss--one of the most intense." (Like Wilde, Barthes tends to think in terms of bodily pleasure.) Unfortunately, paradoxical formulae are not quite meaningless because, as Barthes himself realizes, "both sides of the paradigm [doxa/paradoxa] are glued together in [a] complicitous fashion." Noninvert, when all is said and done, means noninvert.

Oddly enough, Barthes does not reject every gay male stereotype in an attempt to exempt (homo)sexuality from meaning. Barthes rejects sexual inversion, but embraces "tricking" and "cruising," activities that he claims represent true sexual liberation. (Not that they did so for Barthes himself; his autobiographical texts suggest he had an unhappy love life.)

People who "trick," he writes, neither "are" nor "aren't" homosexual. They refuse "to proclaim [themselves] something . . . at the behest of a vengeful Other, to enter into his discourse, to argue with him, to seek from him a scrap of identity." Rather, they are "nothing, or, more precisely, [they are] something [that is] provisional, revocable, insignificant."

People who "cruise" avoid repetition and therefore evade stereotypology: Whereas repetition is a "baleful" theme for Barthes ("stereotype, the same old thing, naturalness as repetition"), cruising, he writes, is "anti-natural, anti-repetition."

It may be that Barthes is simply "protecting" his sexuality here (something he feels all writers do), or at least the macho ("phallocentric") part of his sexuality because whereas sexual inversion feminizes gay men, cruising for tricks is a rather manly (and purportedly desirable) thing to do.

Barthes sees tricking and cruising as senseless in another sense as well. The trick, he writes, "is homogenous to the amorous progression; it is a virtual love, deliberately stopped short on each side, by contract." Likewise, men cruise with "the invincible idea that one will find someone with whom to be in love."

Some gays (who cruise for sex, not love) will find these descriptions unrealistic. Barthes, however, feels that sentimentality, in an age such as ours in which love doesn't make too much sense, is essentially--and even nonparadoxically--insignificant. He finds that love is now "perverse" (meaningless) enough to liberate sexuality beyond any possibility of recuperation, and in a thorough estrangement of the category states that the sentimentality of love as an "alien," and therefore radically transgressive, strength that sexual freedom fighters would do well to deploy.

The reintroduction into sexuality of even "a touch of sentimentality," he writes, would be "the ultimate transgression . . . the transgression of transgression itself . . . [the return of] love . . . but in another place."

Although many theorists support this ludic and loving project, others find it ineffective. They find Barthes far too utopian and apolitical, and believe that true sexual liberation will depend upon "materialist" (Marxist) scholarship. Barthes, however, sees Marxism as ideological, and hence both problematic (part of a futile "war of meanings") and counterrevolutionary. This is why he promulgates--and politicizes--the idea of "semioclasm." According to Barthes, "it is Western discourse as such"--discourse that marginalizes and stereotypes gays and lesbians--"that we must now try to break apart."

Citation Information

Author: Kopelson, Kevin

Entry Title: Barthes, Roland

General Editor: Claude J. Summers

Publication Name: glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture

Publication Date: 2002

Date Last Updated April 14, 2006

Web Address www.glbtq.com/literature/barthes_r.html

Publisher glbtq, Inc.

1130 West Adams

Chicago, IL 60607

Today's Date March 25, 2013

Encyclopedia Copyright: © 2002-2006, glbtq, Inc.

Entry Copyright © 1995, 2002 New England Publishing Associates

Further Readings:

Opacity and the Closet: Queer Tactics in Foucault, Barthes, and Warhol by Nicholas de Villiers

Paperback: 224 pages

Publisher: Univ Of Minnesota Press (April 16, 2012)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0816675716

ISBN-13: 978-0816675715

Amazon: Opacity and the Closet: Queer Tactics in Foucault, Barthes, and Warhol

Amazon Kindle: Opacity and the Closet: Queer Tactics in Foucault, Barthes, and Warhol

Opacity and the Closet interrogates the viability of the metaphor of “the closet” when applied to three important queer figures in postwar American and French culture: the philosopher Michel Foucault, the literary critic Roland Barthes, and the pop artist Andy Warhol. Nicholas de Villiers proposes a new approach to these cultural icons that accounts for the queerness of their works and public personas.

Rather than reading their self-presentations as “closeted,” de Villiers suggests that they invent and deploy productive strategies of “opacity” that resist the closet and the confessional discourse associated with it. Deconstructing binaries linked with the closet that have continued to influence both gay and straight receptions of these intellectual and pop celebrities, de Villiers illuminates the philosophical implications of this displacement for queer theory and introduces new ways to think about the space they make for queerness.

Using the works of Foucault, Barthes, and Warhol to engage each other while exploring their shared historical context, de Villiers also shows their queer appropriations of the interview, the autobiography, the diary, and the documentary-forms typically linked to truth telling and authenticity.

More LGBT History at my website: www.elisarolle.com/, My Ramblings/Gay Classics

This journal is friends only. This entry was originally posted at http://reviews-and-ramblings.dreamwidth.org/3518361.html. If you are not friends on this journal, Please comment there using OpenID.