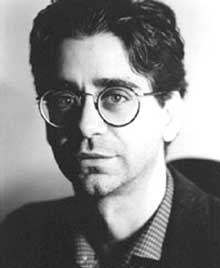

Eminent Outlaws: Aaron Copland (November 14, 1900 - December 2, 1990)

Aaron Copland (November 14, 1900 - December 2, 1990) was an American composer, composition teacher, writer, and later in his career a conductor of his own and other American music. He was instrumental in forging a distinctly American style of composition, and is often referred to as "the Dean of American Composers". He is best known to the public for the works he wrote in the 1930s and 40s in a deliberately more accessible style than his earlier pieces, including the ballets Appalachian Spring, Billy the Kid, Rodeo and his Fanfare for the Common Man. The open, slowly changing harmonies of many of his works are archetypical of what many people consider to be the sound of American music, evoking the vast American landscape and pioneer spirit. However, he wrote music in different styles at different periods of his life: his early works incorporated jazz or avant-garde elements whereas his later music incorporated serial techniques. In addition to his ballets and orchestral works he produced music in many other genres including chamber music, vocal works, opera and film scores.

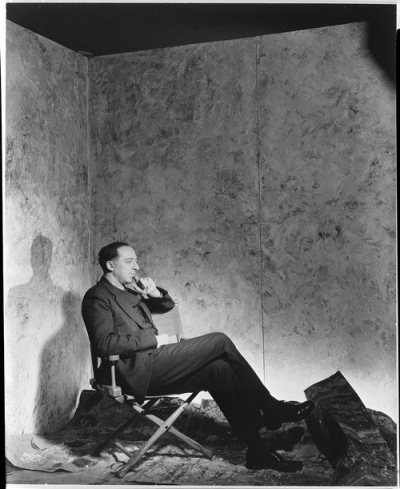

by George Platt Lynes

Aaron Copland and Victor Kraft

Aaron Copland was born in Brooklyn of Lithuanian Jewish descent, the last of five children, on November 14, 1900. Before emigrating from Russia to the United States, Copland's father, Harris Morris Copland, Anglicized his surname "Kaplan" to "Copland" while waiting in Scotland en route to America. Throughout his childhood, Copland and his family lived above his parents' Brooklyn shop, H.M. Copland's, at 628 Washington Avenue (which Aaron would later describe as "a kind of neighborhood Macy's"), on the corner of Dean Street and Washington Avenue, and most of the children helped out in the store. His father was a staunch Democrat. The family members were active in Congregation Baith Israel Anshei Emes, where Aaron celebrated his Bar Mitzvah. Not especially athletic, the sensitive young man became an avid reader and often read Horatio Alger stories on his front steps.

Copland's father had no musical interest at all, but his mother, Sarah Mittenthal Copland, sang and played the piano, and arranged for music lessons for her children. Of his siblings, oldest brother Ralph was the most advanced musically, proficient on the violin, while his sister Laurine had the strongest connection with Aaron, giving him his first piano lessons, promoting his musical education, and supporting him in his musical career. She attended the Metropolitan Opera School and was a frequent opera goer. She often brought home libretti for Aaron to study. Copland attended Boys' High School and in the summer went to various camps. Most of his early exposure to music was at Jewish weddings and ceremonies, and occasional family musicales.

At the age of eleven, Copland devised an opera scenario he called Zenatello, which included seven bars of music, his first notated melody. From 1913 to 1917 he took music lessons with Leopold Wolfsohn, who taught him the standard classical fare. Copland's first public music performance was at a Wanamaker recital.

By the age of 15, after attending a concert by composer-pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Copland decided to become a composer. After attempts to further his music study from a correspondence course, Copland took formal lessons in harmony, theory, and composition from Rubin Goldmark, a noted teacher and composer of American music (who had given George Gershwin three lessons). Goldmark gave the young Copland a solid foundation, especially in the Germanic tradition, as he stated later: "This was a stroke of luck for me. I was spared the floundering that so many musicians have suffered through incompetent teaching." But Copland also commented that the maestro had "little sympathy for the advanced musical idioms of the day" and his "approved" composers ended with Richard Strauss.

Copland's graduation piece from his studies with Goldmark was a three-movement piano sonata in a Romantic style. But he had also composed more original and daring pieces which he did not share with his teacher. In addition to regularly attending the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Symphony, where he heard the standard classical repertory, Copland continued his musical development through an expanding circle of musical friends. After graduating from high school, Copland played in dance bands. Continuing his musical education, he received further piano lessons from Victor Wittgenstein, who found his student to be "quiet, shy, well-mannered, and gracious in accepting criticism." Copland's fascination with the Russian Revolution and its promise for freeing the lower classes drew a rebuke from his father and uncles. In spite of that, in his early adult life Copland would develop friendships with people with socialist and communist leanings.

From 1917 to 1921, Copland composed juvenile works of short piano pieces and art songs. Copland's passion for the latest European music, plus glowing letters from his friend Aaron Schaffer, inspired him to go to Paris for further study. His father wanted him to go to college, but his mother's vote in the family conference allowed him to give Paris a try. On arriving in France, he studied at the Fontainebleau School of Music with noted pianist and pedagogue Isidor Philipp and with Paul Vidal. But finding Vidal too much like Goldmark, Copland switched to famed teacher Nadia Boulanger, then aged thirty-four. He had initial reservations: "No one to my knowledge had ever before thought of studying with a woman." She interviewed him, and recalled later: "One could tell his talent immediately."

Boulanger had as many as forty students at once and employed a formal regimen that Copland had to follow, too. Copland found her incisive mind much to his liking and stated: "This intellectual Amazon is not only professor at the Conservatoire, is not only familiar with all music from Bach to Stravinsky, but is prepared for anything worse in the way of dissonance. But make no mistake...A more charming womanly woman never lived." Though he planned on only one year abroad, he studied with her for three years, finding her eclectic approach inspired his own broad musical taste.

Adding to the heady cultural atmosphere of the early 1920s in Paris was the presence of expatriate American writers Paul Bowles, Ernest Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound, as well as artists like Picasso, Chagall, and Modigliani. Also influential on the new music were the French intellectuals Marcel Proust, Paul Valéry, Sartre, and André Gide, the latter cited by Copland as being his personal favorite and most read. Travels to Italy, Austria, and Germany rounded out Copland's musical education. During his stay in Paris, Copland began writing musical critiques, the first on Gabriel Fauré, which helped spread his fame and stature in the music community. Instead of wallowing in self-pity and self-destruction like many of the expatriate members of the Lost Generation, Copland returned to America optimistic and enthusiastic about the future.

Upon returning to the US, Copland was determined to make his way as a full-time composer. He rented a studio apartment on New York City's Upper West Side, which kept him close to Carnegie Hall and other musical venues and publishers. He remained in that area for the next thirty years, later moving to Westchester County, New York. Copland lived frugally and survived financially with help from two $2,500 Guggenheim Fellowships-one in 1925 and one in 1926. Lecture-recitals, awards, appointments, and small commissions, plus some teaching, writing, and personal loans kept him afloat in the subsequent years through World War II. Also important were wealthy patrons who supported the arts community during the Depression, underwriting performances, publication, and promotion of musical events and composers.

Copland's compositions in the early 1920s reflected the prevailing "modernist" attitude among intellectuals: that they were a small vanguard leading the way for the masses, who would only come to appreciate their efforts over time. In this view, music and the other arts need be accessible to only a select cadre of the enlightened. Toward this end, Copland formed the Young Composer's Group, modeled after France's "Six", gathering together promising young composers, acting as their guiding spirit.

Soon after his return, Copland was introduced to the artistic circle of Alfred Stieglitz and met many of the leading artists of that time. Stieglitz's conviction that the American artist should reflect "the ideas of American Democracy" influenced Copland and a whole generation of artists and photographers, including Paul Strand, Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, Georgia O'Keeffe, and Walker Evans. Evans' photographs inspired portions of Copland's opera The Tender Land.

In his quest to take up Stieglitz's challenge, Copland had few established American contemporaries to emulate apart from Carl Ruggles and the reclusive Charles Ives, although the 1920s were Golden Years for American popular music and jazz, with George Gershwin, Bessie Smith, and Louis Armstrong leading the way. Later, however, Copland joined up with his younger contemporaries and formed a group termed the "commando unit," which included Roger Sessions, Roy Harris, Virgil Thomson, and Walter Piston. They collaborated in joint concerts showcasing their work to new audiences.

Copland's relationship with the "commando unit" was one of both support and rivalry, and he played a key role in keeping them together. The five young American composers helped promote each other and their works but also had testy exchanges, inflamed by the assertion of the press that Copland was the "truly American" composer. Going beyond the five, Copland was generous with his time with nearly every American young composer he met during his life, later earning the title the "Dean of American Music."

Mounting troubles with the Symphonic Ode (1929) and Short Symphony (1933) caused him to rethink the paradigm of composing orchestral music for a select group, as it was a financially contradictory approach, particularly in the Depression. In many ways, this shift mirrored the German idea of Gebrauchsmusik ("music for use"), as composers sought to create music that could serve a utilitarian as well as artistic purpose. This approach encompassed two trends: first, music that students could easily learn, and second, music which would have wider appeal, such as incidental music for plays, movies, radio, etc. Copland undertook both goals, starting in the mid 1930s.

Perhaps motivated by the plight of children during the Depression, around 1935 Copland began to compose musical pieces for young audiences, in accordance with the first goal of American Gebrauchsmusik. These works included piano pieces (The Young Pioneers) and an opera (The Second Hurricane).

During the Depression years, Copland traveled extensively to Europe, Africa, and Mexico. He formed an important friendship with Mexican composer Carlos Chávez and would return often to Mexico for working vacations conducting engagements During his initial visit to Mexico, Copland began composing the first of his signature works, El Salón México, which he completed four years later in 1936. This and other incidental commissions fulfilled the second goal of American Gebrauchsmusik, creating music of wide appeal.

During this time, he composed (for radio broadcast) "Prairie Journal," one of his first pieces to convey the landscape of the American West. Branching out into theater, Copland also played an important role providing musical advice and inspiration to The Group Theater-Stella Adler's and Lee Strasberg's "method" acting school. The Group Theater followed Copland's musical agenda and focused on plays that illuminated the American experience. After Hitler and Mussolini's attacks on Spain in 1936, leftist parties had united in a Popular Front against Fascism. Many Group Theater members were influenced by Marxism and other progressive philosophies, and several had joined the Communist Party, including Elia Kazan and Clifford Odets. Copland also had contact later with other major American playwrights, including Thorton Wilder, William Inge, Arthur Miller, and Edward Albee, and considered projects with all of them. During the 1930s, Copland wrote incidental music for several plays, including Irwin Shaw's "Quiet City" (1939), considered one of his most personal and poignant scores.

In 1939, Copland completed his first two Hollywood film scores, for Of Mice and Men and Our Town, and received sizable commissions. In the same year, he composed the radio score "John Henry", based on the folk ballad. But it wasn’t until the worldwide market for classical recordings boomed after World War II that he achieved economic security. Even after securing a comfortable income, he continued to write, teach, lecture, and, eventually, conduct.

Demonstrating his broad range, Copland in the 1930s began composing music for ballet, including his highly successful Billy the Kid (1939), the second of four ballets he scored (after Hear Ye! Hear Ye! (1934)). Copland's ballet music established him as an authentic composer of American music much as Stravinsky's ballet scores established him with Russian music. Copland's timing was excellent; he helped fill a vacuum for the American choreographers who needed suitable music to score their own nationalistic dance repertory.

In keeping with the wartime period, Copland's "Piano Sonata" (1941) was a piece characterized as "grim, nervous, elegiac, with pervasive bell-like tolling of alarm and mourning." It was later adapted to "Day on Earth," a landmark American dance by Doris Humphrey.

Copland started to publish some of his lectures in the 1930s, "What to Listen for in Music" being one of the most notable of his writings. He also took a leadership role in the American Composers Alliance, whose mission was "to regularize and collect all fees pertaining to performance of their copyrighted music" and "to stimulate interest in the performance of American music." Copland eventually moved over to rival ASCAP. Through royalties and with his great success from 1940 on, Copland amassed a multi-million dollar fortune by the time of his death.

The decade of the 1940s was arguably Copland's most productive, and it firmly established his worldwide fame. His two ballet scores for Rodeo (1942) and Appalachian Spring (1944) were huge successes. His pieces Lincoln Portrait and Fanfare for the Common Man have become patriotic standards (See Popular works, below). Also important was the Third Symphony. Composed in a two-year period from 1944 to 1946, it became the most popular American symphony of the 20th Century.

In 1945, Copland contributed to Jubilee Variation, a work commissioned by the Cincinnati Symphony in which ten American composers collaborated, but the piece is seldom heard in the concert hall. Copland's In the Beginning (1947) is a choral work using the first chapter and the first seven verses of the second chapter of Genesis from the King James Version of the Bible and is a masterpiece of the choral repertory.

Copland's Clarinet Concerto (1948), scored for solo clarinet, strings, harp, and piano, was a commission piece for bandleader and clarinetist Benny Goodman and a complement to Copland's earlier jazz-influenced work, the Piano Concerto (1926). His "Four Piano Blues" is an introspective composition with a jazz influence.

Copland finished the 1940s with two film scores, one for William Wyler's 1949 film The Heiress and one for the film adaptation of John Steinbeck's novel The Red Pony.

In 1949, he returned to Europe to find Pierre Boulez dominating the group of post-War radical musicians. He also met with the proponents of the twelve-tone school (Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and Alban Berg) and found himself having greater sympathy for them than he did for the French, whom he felt were drifting too far from classical principles to suit his taste.

In 1950, Copland received a Fulbright scholarship to study in Rome, which he did the following year. Around this time, he also composed his Piano Quartet, adopting Schoenberg's twelve-tone method of composition, and Old American Songs (1950), premiered by William Warfield.

Because of the political climate of that era, A Lincoln Portrait was withdrawn from the 1953 inaugural concert for President Eisenhower. That same year, Copland was called before Congress, where he testified that he was never a communist.

Despite the difficulties that his suspected Communist sympathies posed, Copland nonetheless traveled extensively during the 1950s and early 1960s, observing the avant-garde styles of Europe while experiencing the new school of Soviet music. In addition, he was rather taken with the work of Toru Takemitsu while in Japan and began a correspondence with him that would last over the next decade. Copland wrote of the Japanese composer: "He has the 'pure gold' touch, he chooses his notes carefully and meaningfully." Copland also gained exposure to the latest musical trends in Poland and Scandinavia. In observing these new musical forms, Copland revised his text "The New Music" with comments on the styles that he encountered. In particular, while Copland explained the importance of the work of John Cage and others (in his chapter titled "The Music of Chance"), he found that these radical trends in music which appealed to those "who enjoy teetering on the edge of chaos" were less likely to gain the appreciation of a wider audience "who envisage art as a bulwark against the irrationality of man's nature." As he summarized: "I’ve spent most of my life trying to get the right note in the right place. Just throwing it open to chance seems to go against my natural instincts."

In 1954, Copland received a commission from Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein to create music for the opera The Tender Land, based on James Agee's Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Copland had been wary of writing an opera, being especially aware of the pitfalls of that form, including weak libretti and demanding production values. Nevertheless, Copland decided to try his hand at "la forme fatale," especially as the 1950s were boom times for American playwrights, with Arthur Miller, Clifford Odets and Thorton Wilder doing some of their best work. Originally two acts, The Tender Land was later expanded to three. As Copland feared, critics found the libretto to be the opera's weakness, and he later stated: "I admit that if I have one regret it is that I never did write a 'grand opera'." In spite of its flaws, the opera has established itself as one of the few American operas in the standard repertory.

Copland exerted a major influence on the compositional style of an entire generation of American composers, including his friend and protégé Leonard Bernstein. Bernstein was considered the finest conductor of Copland's works and cites Copland's "aesthetic, simplicity with originality" as being his strongest and most influential traits.

From the 1960s onward, Copland's activities turned more from composing to conducting. Though not enamored with the prospect, he found himself without new ideas for composition, saying: "It was exactly as if someone had simply turned off a faucet." Copland was a frequent guest conductor of orchestras in the US and the UK. He made a series of recordings of his music, primarily for Columbia Records. In 1960, RCA Victor released Copland's recordings with the Boston Symphony Orchestra of the orchestral suites from Appalachian Spring and The Tender Land; these recordings were later reissued on CD, as were most of Copland's Columbia recordings (by Sony).

From 1960 to his death, he resided at Cortlandt Manor, New York. His home, known as Rock Hill, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2003. It was further designated a National Historic Landmark in 2008. Copland's health deteriorated through the 1980s, and he died of Alzheimer's disease and respiratory failure on December 2, 1990, in North Tarrytown, New York (now Sleepy Hollow). Much of his large estate was bequeathed to the creation of the Aaron Copland Fund for Composers, which bestows over $600,000 per year to performing groups.

Copland was a calm, affable, modest, and mild-mannered man, who masked his feelings. Even friends found it hard to crack his façade. Although shy, he preferred to be in a crowd rather than alone. He lived simply and approached composing in the same manner. He was an avid reader. He always remained thrifty, even after he achieved substantial wealth. In company, Copland could be "almost devilishly droll" and fun-loving. His tact served him well in his private life and in his public life as a moderator, committee man, and teacher. Copland was a constant and diligent worker and a night owl, who composed primarily at the piano and at a relatively slow pace. He was careful in assembling and storing his documents and scores, so he could later find and re-use earlier ideas and themes.

Deciding not to follow the example of his father, a solid Democrat, Copland never enrolled as a member of any political party, but he espoused a general progressive view and had strong ties with numerous colleagues and friends in the Popular Front, including Odets. Copland supported the Communist Party USA ticket during the 1936 presidential election, at the height of his involvement with The Group Theater, and remained a committed opponent of militarism and the Cold War, which he regarded as having been instigated by the United States. He condemned it as, "almost worse for art than the real thing". Throw the artist "into a mood of suspicion, ill-will, and dread that typifies the cold war attitude and he'll create nothing". In keeping with these attitudes, Copland was a strong supporter of the Presidential candidacy of Henry A. Wallace on the Progressive Party ticket. As a result, he was later investigated by the FBI during the Red scare of the 1950s and found himself blacklisted. Copland was included on an FBI list of 151 artists thought to have Communist associations. Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn questioned Copland about his lecturing abroad, neglecting completely Copland's works which made a virtue of American values. Outraged by the accusations, many members of the musical community held up Copland's music as a banner of his patriotism. The investigations ceased in 1955 and were closed in 1975. Though taxing of his time, energy, and emotional state, Copland's career and international artistic reputation were not seriously affected by the McCarthy probes. In any case, beginning in 1950, Copland, who had been appalled at Stalin's persecution of Shostakovich and other artists, began resigning from participation in leftist groups. He decried the lack of artistic freedom in the Soviet Union, and in his 1954 Norton lecture he asserted that loss of freedom under Soviet Communism deprived artists of "the immemorial right of the artist to be wrong." He began to vote Democratic, first for Stevenson and then for Kennedy.

Copland is documented as a gay man in author Howard Pollack's biography, Aaron Copland: The Life and Work of an Uncommon Man. Like many of his contemporaries he guarded his privacy, especially in regard to his homosexuality, providing very few written details about his private life. However, he was one of the few composers of his stature to live openly and travel with his lovers, most of whom were talented, much younger men. Among Copland's love affairs, most of which lasted for only a few years yet became enduring friendships, were ones with photographer Victor Kraft, artist Alvin Ross, pianist Paul Moor, dancer Erik Johns, and composer John Brodbin Kennedy.

Burial: Cremated, Ashes scattered in a bower at the Tanglewood Music Center in Berkshire County, Massachusetts

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aaron_CoplandShortly before the war, a young Harvard undergraduate named Leonard Bernstein made one of his first visit to Manhattan. On November 14, 1937, Aaron Copland, the great gay American composer, invited the budding musician to a birthday party at his New York loft on West 63d Street. The room was filled with gay and bisexual intellectuals, including Paul Bowles (then known only as a composer) and Virgil Thomson. When Copland learned that Bernstein loved his Piano Variations, he dared the Harvard boy to play them. "It'll ruin the party", said Bernstein. "Not this party", Copland replied, and the guests were mesmerized by Bernstein's performance.

During the next decade, Copland would become an important father figure for Bernstein, as well as his composition adviser. One of Bernstein's biographers, Humphrey Burton, believes Bernstein and Copland may also have been lovers. "He taught me a tremendous amount about taste, style and consistency in music", Bernstein said of his mentor. --The Gay Metropolis: The Landmark History of Gay Life in America by Charles Kaiser

Further Readings:

Aaron Copland: THE LIFE AND WORK OF AN UNCOMMON MAN (Music in American Life) by Howard Pollack

Paperback: 728 pages

Publisher: University of Illinois Press (March 8, 2000)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0252069005

ISBN-13: 978-0252069000

Amazon: Aaron Copland: THE LIFE AND WORK OF AN UNCOMMON MAN

One of America's most beloved and accomplished composers, Aaron Copland played a crucial role in the coming of age of American music. This substantial biography is the first full-length scholarly study of Copland's life and work. A conductor, music critic, and teacher who wrote clearly and accessibly about music, Copland composed some of the twentieth century's most familiar works - Billy the Kid, Rodeo, Appalachian Spring, Fanfare for the Common Man - in addition to a wealth of music for opera, ballet, chorus, orchestra, chamber ensemble, band, radio, and film. Howard Pollack's expansive and detailed biography examines Copland's musical development, his political sympathies, his personal life, and his tireless encouragement of younger composers, presenting a balanced and skillfully wrought portrait of an American original.

The Selected Correspondence of Aaron Copland

Hardcover: 288 pages

Publisher: Yale University Press; annotated edition edition (April 26, 2006)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0300111215

ISBN-13: 978-0300111217

Amazon: The Selected Correspondence of Aaron Copland

This is the first book devoted to the correspondence of composer Aaron Copland, covering his life from age eight to eighty-seven. The chronologically arranged collection includes letters to many significant figures in American twentieth-century music as well as Copland’s friends, family, teachers, and colleagues. Selected for readability, interest, and the light they cast upon the composer’s thoughts and career, the letters are carefully annotated and each published in its entirety.

Copland was a gifted and natural letter writer who revealed much more about himself in his letters than in formal writings in which he was conscious of his position as spokesman for modern music. The collected letters offer insights into his music, personality, and ideas, along with fascinating glimpses into the lives of such other well-known musicians as Leonard Bernstein, Carlos Chávez, William Schuman, and Virgil Thomson.

Aaron Copland and His World (Bard Music Festival) by Carol J. Oja & Judith Tick

Paperback: 568 pages

Publisher: Princeton University Press (August 1, 2005)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0691124701

ISBN-13: 978-0691124704

Amazon: Aaron Copland and His World

Aaron Copland and His World reassesses the legacy of one of America's best-loved composers at a pivotal moment--as his life and work shift from the realm of personal memory to that of history. This collection of seventeen essays by distinguished scholars of American music explores the stages of cultural change on which Copland's long life (1900 to 1990) unfolded: from the modernist experiments of the 1920s, through the progressive populism of the Great Depression and the urgencies of World War II, to postwar political backlash and the rise of serialism in the 1950s and the cultural turbulence of the 1960s.

Continually responding to an ever-changing political and cultural panorama, Copland kept a firm focus on both his private muse and the public he served. No self-absorbed recluse, he was very much a public figure who devoted his career to building support systems to help composers function productively in America. This book critiques Copland's work in these shifting contexts.

The topics include Copland's role in shaping an American school of modern dance; his relationship with Leonard Bernstein; his homosexuality, especially as influenced by the writings of Andr Gide; and explorations of cultural nationalism. Copland's rich correspondence with the composer and critic Arthur Berger, who helped set the parameters of Copland's reception, is published here in its entirety, edited by Wayne Shirley. The contributors include Emily Abrams, Paul Anderson, Elliott Antokoletz, Leon Botstein, Martin Brody, Elizabeth Crist, Morris Dickstein, Lynn Garafola, Melissa de Graaf, Neil Lerner, Gail Levin, Beth Levy, Vivian Perlis, Howard Pollack, and Larry Starr.

The Queer Composition of America's Sound: Gay Modernists, American Music, and National Identity by Nadine Hubbs

Paperback: 293 pages

Publisher: University of California Press; 1 edition (October 18, 2004)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0520241851

ISBN-13: 978-0520241855

Amazon: The Queer Composition of America's Sound: Gay Modernists, American Music, and National Identity

In this vibrant and pioneering book, Nadine Hubbs shows how a gifted group of Manhattan-based gay composers were pivotal in creating a distinctive "American sound" and in the process served as architects of modern American identity. Focusing on a talented circle that included Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, Leonard Bernstein, Marc Blitzstein, Paul Bowles, David Diamond, and Ned Rorem, The Queer Composition of America's Sound homes in on the role of these artists' self-identification--especially with tonal music, French culture, and homosexuality--in the creation of a musical idiom that even today signifies "America" in commercials, movies, radio and television, and the concert hall.