Process Art; Viscera.

John Cage.

I once asked Arragon, the historian, how history was written. He said, "You have to invent it." When I wish as now to tell of critical incidents, persons, and events that have influenced my life and work, the true answer is all of the incidents were critical, all of the people influenced me, everything that happened and that is still happening influences me.

My father was an inventor. He was able to find solutions for problems of various kinds, in the fields of electrical engineering, medicine, submarine travel, seeing through fog, and travel in space without the use of fuel. He told me that if someone says "can't" that shows you what to do. He also told me that my mother was always right even when she was wrong...

...I dropped out after two years. Thinking I was going to be a writer, I told Mother and Dad I should travel to Europe and have experiences rather than continue in school. I was shocked at college to see one hundred of my classmates in the library all reading copies of the same book. Instead of doing as they did, I went into the stacks and read the first book written by an author whose name began with Z. I received the highest grade in the class. That convinced me that the institution was not being run correctly. I left...

...When I asked Schoenberg to teach me, he said, "You probably can't afford my price." I said, "Don't mention it; I don't have any money." He said, "Will you devote your life to music?" This time I said "Yes." He said he would teach me free of charge. I gave up painting and concentrated on music. After two years it became clear to both of us that I had no feeling for harmony. For Schoenberg, harmony was not just coloristic: it was structural. It was the means one used to distinguish one part of a composition from another. Therefore he said I'd never be able to write music. "Why not?" "You'll come to a wall and won't be able to get through." "Then I'll spend my life knocking my head against that wall."

...It was there that I discovered what I called micro-macrocosmic rhythmic structure. The large parts of a composition had the same proportion as the phrases of a single unit. Thus an entire piece had that number of measures that had a square root. This rhythmic structure could be expressed with any sounds, including noises, or it could be expressed not as sound and silence but as stillness and movement in dance. It was my response to Schoenberg's structural harmony. It was also at the Cornish School that I became aware of Zen Buddhism, which later, as part of oriental philosophy, took the place for me of psychoanalysis. I was disturbed both in my private life and in my public life as a composer. I could not accept the academic idea that the purpose of music was communication, because I noticed that when I conscientiously wrote something sad, people and critics were often apt to laugh. I determined to give up composition unless I could find a better reason for doing it than communication. I found this answer from Gira Sarabhai, an Indian singer and tabla player: The purpose of music is to sober and quiet the mind, thus making it susceptible to divine influences. I also found in the writings of Ananda K. Coomaraswammy that the responsibility of the artist is to imitate nature in her manner of operation. I became less disturbed and went back to work.

...When I was young and still writing an unstructured music, albeit methodical and not improvised, one of my teachers, Adolph Weiss, used to complain that no sooner had I started a piece than I brought it to an end. I introduced silence. I was a ground, so to speak, in which emptiness could grow.

In the late forties I found out by experiment (I went into the anechoic chamber at Harvard University) that silence is not acoustic. It is a change of mind, a turning around. I devoted my music to it. My work became an exploration of non-intention. To carry it out faithfully I have developed a complicated composing means using I Ching chance operations, making my responsibility that of asking questions instead of making choices.

The Buddhist texts to which I often return are the Huang-Po Doctrine of Universal Mind (in Chu Ch'an's first translation, published by the London Buddhist Society in 1947), Neti Neti by L. C. Beckett of which (as I say in the introduction to my Norton Lectures at Harvard) my life could be described as an illustration, and the Ten Oxherding Pictures (in the version that ends with the return to the village bearing gifts of a smiling and somewhat heavy monk, one who had experienced Nothingness). Apart from Buddhism and earlier I had read the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna. Ramakrishna it was who said all religions are the same, like a lake to which people who are thirsty come from different directions, calling its water by different names. Furthermore this water has many different tastes. The taste of Zen for me comes from the admixture of humor, intransigence, and detachment. It makes me think of Marcel Duchamp, though for him we would have to add the erotic.

...My music now makes use of time-brackets, sometimes flexible, sometimes not. There are no scores, no fixed relation of parts. Sometimes the parts are fully written out, sometimes not. The title of my Norton lectures is a reference to a brought-up-to-date version of Compositions in Retrospect:

MethodStructureIntentionDisciplineNotationIndeterminacy

InterpenetrationImitationDevotionCircumstancesVariableStructure

NonunderstandingContingencyInconsistencyPerformance(I-VI).

When it is published, for commercial convenience, it will just be called IVI.

*

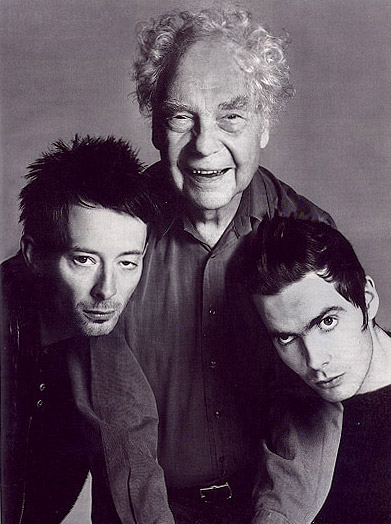

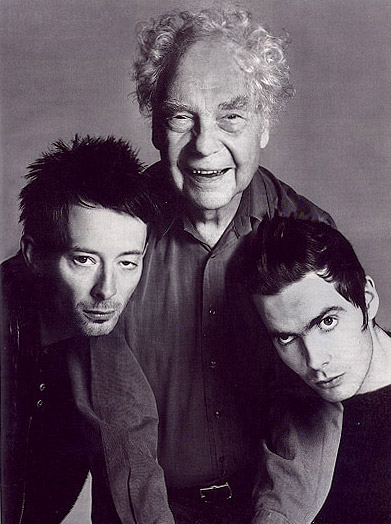

Thom Yorke, Merce Cunningham, Jon Thor Birgisson

Spot the symmetry in this photograph. Seriously.

*

...It was at Black Mountain College that I made what is sometimes said to be the first happening. The audience was seated in four isometric triangular sections, the apexes of which touched a small square performance area that they faced and that led through the aisles between them to the large performance area that surrounded them. Disparate activities, dancing by Merce Cunningham, the exhibition of paintings and the playing of a Victrola by Robert Rauschenberg, the reading of his poetry by Charles Olsen or hers by M. C. Richards from the top of a ladder outside the audience, the piano playing of David Tudor, my own reading of a lecture that included silences from the top of another ladder outside the audience, all took place within chance-determined periods of time within the over-all time of my lecture. It was later that summer that I was delighted to find in America's first synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, that the congregation was seated in the same way, facing itself.

From Rhode Island I went on to Cambridge and in the anechoic chamber at Harvard University heard that silence was not the absence of sound but was the unintended operation of my nervous system and the circulation of my blood. It was this experience and the white paintings of Rauschenberg that led me to compose 4'33", which I had described in a lecture at Vassar College some years before when I was in the flush of my studies with Suzuki (A Composer's Confessions, 1948), my silent piece.

...Just as my notion of rhythmic structure followed Schoenberg's structural harmony, and my silent piece followed Robert Rauschenberg's white paintings, so my Music of Changes, composed by means of I Ching chance operations, followed Morton Feldman's graph music, music written with numbers for any pitches, the pitches notated only as high, middle, or low. Not immediately, but a few years later, I was to move from structure to process, from music as an object having parts, to music without beginning, middle, or end, music as weather. In our collaborations Merce Cunningham's choreographies are not supported by my musical accompaniments. Music and dance are independent but coexistant...

*

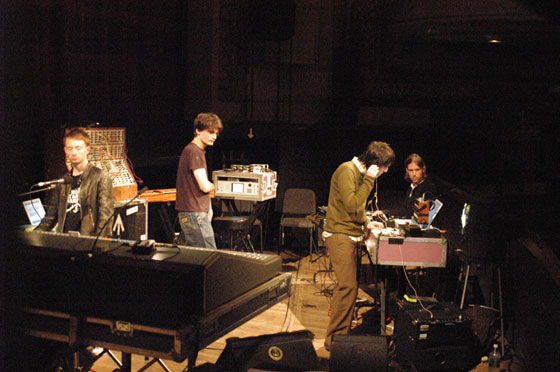

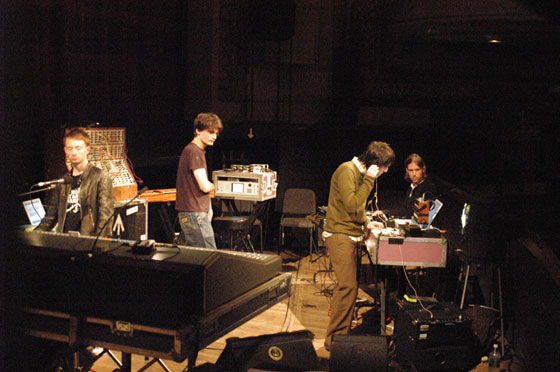

this ambient 20 minute song is split into three individual tracks and derives its puzzling title from the only spoken sounds uttered in the piece. it is composed of four primary instruments: piano, music box, miked-up ballet shoes and electronic playback. the song was written for merce cunningham's dance piece 'split sides' which was premiered october 14th 2003 in the brooklyn academy of music. the music and choreography of split sides were composed independently of each other and were first introduced to one another on the premiere night, leaving the musicians a window of opporunity for improvisation. sigur rós left room for interaction with the choreography when composing the song and watched the dancers' movements closely as they turned their music boxes and tapped their ballet shoes.

the song's final chapter, di do, features cut-up samples of choreographer merce cunningham's voice, which foreground the rhythm of the song's crescendo. at this point in the premiere performance of split sides, a stunning coincidental synchronisation occurred between the dancers' movements and the music. [sigur ros' ba ba ti ki di do]

I am listening to The Eraser.

*

It was in the fifties that I left the city and went to the country. There I found Guy Nearing, who guided me in my study of mushrooms and other wild edible plants. With three other friends we founded the New York Mycological Society. Nearing helped us also with the lichen about which he had written and printed a book. When the weather was dry and the mushrooms weren't growing we spent our time with the lichen.

In the sixties the publication of both my music and my writings began. Whatever I do in the society is made available for use. An experience I had in Hawaii turned my attention to the work of Buckminster Fuller and the work of Marshall McLuhan. Above the tunnel that connects the southern part of Oahu with the northern there are crenelations at the top of the mountain range as on a medieval castle. When I asked about them, I was told they had been used for self-protection while shooting poisoned arrows on the enemy below. Now both sides share the same utilities. Little more than a hundred years ago the island was a battlefield divided by a mountain range. Fuller's world map shows that we live on a single island. Global village (McLuhan), Spaceship Earth (Fuller). Make an equation between human needs and world resources (Fuller). I began my Diary: How to Improve the World: You Will Only Make Matters Worse. Mother said, "How dare you!"

I don't know when it began. But at Edwin Denby's loft on 21st Street, not at the time but about the place, I wrote my first mesostic. It was a regular paragraph with the letters of his name capitalized. Since then I have written them as poems, the capitals going down the middle, to celebrate whatever, to support whatever, to fulfill requests, to initiate my thinking or my nonthinking (Themes and Variations is the first of a series of mesostic works: to find a way of writing that, though coming from ideas, is not about them but produces them). I have found a variety of ways of writing mesostics: Writings through a source: Rengas (a mix of a plurality of source mesostics), autokus, mesostics limited to the words of the mesostic itself, and "globally," letting the words come from here and there through chance operations in a source text.

I was invited by Irwin Hollander to make lithographs. Actually it was an idea Alice Weston had (Duchamp had died. I had been asked to say something about him. Jasper Johns was also asked to do this. He said, "I don't want to say anything about Marcel." I made Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel: eight plexigrams and two lithographs. Whether this brought about the invitation or not, I do not know. I was invited by Kathan Brown to the Crown Point Press, then in Oakland, California, to make etchings. I accepted the invitation because years before I had not accepted one from Gira Sarabhai to walk with her in the Himalayas. I had something else to do.

Once Kathan Brown said, "You wouldn't just sit down and draw." Now I do: drawings around stones, stones placed on a grid at chance determined points. These drawings have also made musical notation: Renga, Score and Twenty-three Parts, and Ryoanji (but drawing from left to right, halfway around a stone). Ray Kass, an artist who teaches watercolor at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, became interested in my graphic work with chance operations. With his aid and that of students he enlisted I have made fifty-two watercolors. And those have led me to aquatints, brushes, acids, and their combination with fire, smoke, and stones with etchings.

These experiences led me in one instance to compose music in the way I had found to make a series of prints called On the Surface. I discovered that a horizontal line that determined graphic changes, to correspond, had to become a vertical line in the notation of music (Thirty Pieces for Five Orchestras). Time instead of space.

Thinking of orchestra not just as musicians but as people I have made different translations of people to people in different pieces. In Etcetera to being with the orchestra as soloists, letting them volunteer their services from time to time to any one of three conductors. In Etcetera 2/4 Orchestras to begin with four conductors, letting orchestra members from time to time leave the group and play as soloists. In Atlas Eclipticalis and Concert for Piano and Orchestra the conductor is not a governing agent but a utility, providing the time. In Quartet no more than four musicians play at a time, which four constantly changing. Each musician is a soloist. To bring to orchestral society the devotion to music that characterizes chamber music. To build a society one by one. To bring chamber music to the size of orchestra. Music for -----. So far I have written eighteen parts, any of which can be played together or omitted. Flexible time-brackets. Variable structure. A music so to speak that's earthquake proof. Another series without an underlying idea is the group that began with Two, continued with One, Five, Seven, Twenty-three, 1O1, Four, Two2, One2, Three, Fourteen, and Seven2. For each of these works I look for something I haven't yet found. My favorite music is the music I haven't yet heard. I don't hear the music I write. I write in order to hear the music I haven't yet heard.

We are living in a period in which many people have changed their mind about what the use of music is or could be for them. Something that doesn't speak or talk like a human being, that doesn't know its definition in the dictionary or its theory in the schools, that expresses itself simply by the fact of its vibrations. People paying attention to vibratory activity, not in reaction to a fixed ideal performance, but each time attentively to how it happens to be this time, not necessarily two times the same. A music that transports the listener to the moment where he is.

I once asked Arragon, the historian, how history was written. He said, "You have to invent it." When I wish as now to tell of critical incidents, persons, and events that have influenced my life and work, the true answer is all of the incidents were critical, all of the people influenced me, everything that happened and that is still happening influences me.

My father was an inventor. He was able to find solutions for problems of various kinds, in the fields of electrical engineering, medicine, submarine travel, seeing through fog, and travel in space without the use of fuel. He told me that if someone says "can't" that shows you what to do. He also told me that my mother was always right even when she was wrong...

...I dropped out after two years. Thinking I was going to be a writer, I told Mother and Dad I should travel to Europe and have experiences rather than continue in school. I was shocked at college to see one hundred of my classmates in the library all reading copies of the same book. Instead of doing as they did, I went into the stacks and read the first book written by an author whose name began with Z. I received the highest grade in the class. That convinced me that the institution was not being run correctly. I left...

...When I asked Schoenberg to teach me, he said, "You probably can't afford my price." I said, "Don't mention it; I don't have any money." He said, "Will you devote your life to music?" This time I said "Yes." He said he would teach me free of charge. I gave up painting and concentrated on music. After two years it became clear to both of us that I had no feeling for harmony. For Schoenberg, harmony was not just coloristic: it was structural. It was the means one used to distinguish one part of a composition from another. Therefore he said I'd never be able to write music. "Why not?" "You'll come to a wall and won't be able to get through." "Then I'll spend my life knocking my head against that wall."

...It was there that I discovered what I called micro-macrocosmic rhythmic structure. The large parts of a composition had the same proportion as the phrases of a single unit. Thus an entire piece had that number of measures that had a square root. This rhythmic structure could be expressed with any sounds, including noises, or it could be expressed not as sound and silence but as stillness and movement in dance. It was my response to Schoenberg's structural harmony. It was also at the Cornish School that I became aware of Zen Buddhism, which later, as part of oriental philosophy, took the place for me of psychoanalysis. I was disturbed both in my private life and in my public life as a composer. I could not accept the academic idea that the purpose of music was communication, because I noticed that when I conscientiously wrote something sad, people and critics were often apt to laugh. I determined to give up composition unless I could find a better reason for doing it than communication. I found this answer from Gira Sarabhai, an Indian singer and tabla player: The purpose of music is to sober and quiet the mind, thus making it susceptible to divine influences. I also found in the writings of Ananda K. Coomaraswammy that the responsibility of the artist is to imitate nature in her manner of operation. I became less disturbed and went back to work.

...When I was young and still writing an unstructured music, albeit methodical and not improvised, one of my teachers, Adolph Weiss, used to complain that no sooner had I started a piece than I brought it to an end. I introduced silence. I was a ground, so to speak, in which emptiness could grow.

In the late forties I found out by experiment (I went into the anechoic chamber at Harvard University) that silence is not acoustic. It is a change of mind, a turning around. I devoted my music to it. My work became an exploration of non-intention. To carry it out faithfully I have developed a complicated composing means using I Ching chance operations, making my responsibility that of asking questions instead of making choices.

The Buddhist texts to which I often return are the Huang-Po Doctrine of Universal Mind (in Chu Ch'an's first translation, published by the London Buddhist Society in 1947), Neti Neti by L. C. Beckett of which (as I say in the introduction to my Norton Lectures at Harvard) my life could be described as an illustration, and the Ten Oxherding Pictures (in the version that ends with the return to the village bearing gifts of a smiling and somewhat heavy monk, one who had experienced Nothingness). Apart from Buddhism and earlier I had read the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna. Ramakrishna it was who said all religions are the same, like a lake to which people who are thirsty come from different directions, calling its water by different names. Furthermore this water has many different tastes. The taste of Zen for me comes from the admixture of humor, intransigence, and detachment. It makes me think of Marcel Duchamp, though for him we would have to add the erotic.

...My music now makes use of time-brackets, sometimes flexible, sometimes not. There are no scores, no fixed relation of parts. Sometimes the parts are fully written out, sometimes not. The title of my Norton lectures is a reference to a brought-up-to-date version of Compositions in Retrospect:

MethodStructureIntentionDisciplineNotationIndeterminacy

InterpenetrationImitationDevotionCircumstancesVariableStructure

NonunderstandingContingencyInconsistencyPerformance(I-VI).

When it is published, for commercial convenience, it will just be called IVI.

*

Thom Yorke, Merce Cunningham, Jon Thor Birgisson

Spot the symmetry in this photograph. Seriously.

*

...It was at Black Mountain College that I made what is sometimes said to be the first happening. The audience was seated in four isometric triangular sections, the apexes of which touched a small square performance area that they faced and that led through the aisles between them to the large performance area that surrounded them. Disparate activities, dancing by Merce Cunningham, the exhibition of paintings and the playing of a Victrola by Robert Rauschenberg, the reading of his poetry by Charles Olsen or hers by M. C. Richards from the top of a ladder outside the audience, the piano playing of David Tudor, my own reading of a lecture that included silences from the top of another ladder outside the audience, all took place within chance-determined periods of time within the over-all time of my lecture. It was later that summer that I was delighted to find in America's first synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, that the congregation was seated in the same way, facing itself.

From Rhode Island I went on to Cambridge and in the anechoic chamber at Harvard University heard that silence was not the absence of sound but was the unintended operation of my nervous system and the circulation of my blood. It was this experience and the white paintings of Rauschenberg that led me to compose 4'33", which I had described in a lecture at Vassar College some years before when I was in the flush of my studies with Suzuki (A Composer's Confessions, 1948), my silent piece.

...Just as my notion of rhythmic structure followed Schoenberg's structural harmony, and my silent piece followed Robert Rauschenberg's white paintings, so my Music of Changes, composed by means of I Ching chance operations, followed Morton Feldman's graph music, music written with numbers for any pitches, the pitches notated only as high, middle, or low. Not immediately, but a few years later, I was to move from structure to process, from music as an object having parts, to music without beginning, middle, or end, music as weather. In our collaborations Merce Cunningham's choreographies are not supported by my musical accompaniments. Music and dance are independent but coexistant...

*

this ambient 20 minute song is split into three individual tracks and derives its puzzling title from the only spoken sounds uttered in the piece. it is composed of four primary instruments: piano, music box, miked-up ballet shoes and electronic playback. the song was written for merce cunningham's dance piece 'split sides' which was premiered october 14th 2003 in the brooklyn academy of music. the music and choreography of split sides were composed independently of each other and were first introduced to one another on the premiere night, leaving the musicians a window of opporunity for improvisation. sigur rós left room for interaction with the choreography when composing the song and watched the dancers' movements closely as they turned their music boxes and tapped their ballet shoes.

the song's final chapter, di do, features cut-up samples of choreographer merce cunningham's voice, which foreground the rhythm of the song's crescendo. at this point in the premiere performance of split sides, a stunning coincidental synchronisation occurred between the dancers' movements and the music. [sigur ros' ba ba ti ki di do]

I am listening to The Eraser.

*

It was in the fifties that I left the city and went to the country. There I found Guy Nearing, who guided me in my study of mushrooms and other wild edible plants. With three other friends we founded the New York Mycological Society. Nearing helped us also with the lichen about which he had written and printed a book. When the weather was dry and the mushrooms weren't growing we spent our time with the lichen.

In the sixties the publication of both my music and my writings began. Whatever I do in the society is made available for use. An experience I had in Hawaii turned my attention to the work of Buckminster Fuller and the work of Marshall McLuhan. Above the tunnel that connects the southern part of Oahu with the northern there are crenelations at the top of the mountain range as on a medieval castle. When I asked about them, I was told they had been used for self-protection while shooting poisoned arrows on the enemy below. Now both sides share the same utilities. Little more than a hundred years ago the island was a battlefield divided by a mountain range. Fuller's world map shows that we live on a single island. Global village (McLuhan), Spaceship Earth (Fuller). Make an equation between human needs and world resources (Fuller). I began my Diary: How to Improve the World: You Will Only Make Matters Worse. Mother said, "How dare you!"

I don't know when it began. But at Edwin Denby's loft on 21st Street, not at the time but about the place, I wrote my first mesostic. It was a regular paragraph with the letters of his name capitalized. Since then I have written them as poems, the capitals going down the middle, to celebrate whatever, to support whatever, to fulfill requests, to initiate my thinking or my nonthinking (Themes and Variations is the first of a series of mesostic works: to find a way of writing that, though coming from ideas, is not about them but produces them). I have found a variety of ways of writing mesostics: Writings through a source: Rengas (a mix of a plurality of source mesostics), autokus, mesostics limited to the words of the mesostic itself, and "globally," letting the words come from here and there through chance operations in a source text.

I was invited by Irwin Hollander to make lithographs. Actually it was an idea Alice Weston had (Duchamp had died. I had been asked to say something about him. Jasper Johns was also asked to do this. He said, "I don't want to say anything about Marcel." I made Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel: eight plexigrams and two lithographs. Whether this brought about the invitation or not, I do not know. I was invited by Kathan Brown to the Crown Point Press, then in Oakland, California, to make etchings. I accepted the invitation because years before I had not accepted one from Gira Sarabhai to walk with her in the Himalayas. I had something else to do.

Once Kathan Brown said, "You wouldn't just sit down and draw." Now I do: drawings around stones, stones placed on a grid at chance determined points. These drawings have also made musical notation: Renga, Score and Twenty-three Parts, and Ryoanji (but drawing from left to right, halfway around a stone). Ray Kass, an artist who teaches watercolor at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, became interested in my graphic work with chance operations. With his aid and that of students he enlisted I have made fifty-two watercolors. And those have led me to aquatints, brushes, acids, and their combination with fire, smoke, and stones with etchings.

These experiences led me in one instance to compose music in the way I had found to make a series of prints called On the Surface. I discovered that a horizontal line that determined graphic changes, to correspond, had to become a vertical line in the notation of music (Thirty Pieces for Five Orchestras). Time instead of space.

Thinking of orchestra not just as musicians but as people I have made different translations of people to people in different pieces. In Etcetera to being with the orchestra as soloists, letting them volunteer their services from time to time to any one of three conductors. In Etcetera 2/4 Orchestras to begin with four conductors, letting orchestra members from time to time leave the group and play as soloists. In Atlas Eclipticalis and Concert for Piano and Orchestra the conductor is not a governing agent but a utility, providing the time. In Quartet no more than four musicians play at a time, which four constantly changing. Each musician is a soloist. To bring to orchestral society the devotion to music that characterizes chamber music. To build a society one by one. To bring chamber music to the size of orchestra. Music for -----. So far I have written eighteen parts, any of which can be played together or omitted. Flexible time-brackets. Variable structure. A music so to speak that's earthquake proof. Another series without an underlying idea is the group that began with Two, continued with One, Five, Seven, Twenty-three, 1O1, Four, Two2, One2, Three, Fourteen, and Seven2. For each of these works I look for something I haven't yet found. My favorite music is the music I haven't yet heard. I don't hear the music I write. I write in order to hear the music I haven't yet heard.

We are living in a period in which many people have changed their mind about what the use of music is or could be for them. Something that doesn't speak or talk like a human being, that doesn't know its definition in the dictionary or its theory in the schools, that expresses itself simply by the fact of its vibrations. People paying attention to vibratory activity, not in reaction to a fixed ideal performance, but each time attentively to how it happens to be this time, not necessarily two times the same. A music that transports the listener to the moment where he is.