Last post of the year on Daily Kos

Food Fight! Thoughts on liberalism and conservativism inspired by the Preface to Food, Inc.

As some of you may know, I'm a college professor who usually teaches science courses such as biology, environmental science, and geology. This upcoming semester, I will be stretching myself by teaching a course called "The Global Politics of Food." I won't be alone in this; there is a political science professor teaching this course with me. Still, it will be the first non-science course I've taught since I was a substitute teacher ten years ago, so it's going to be an experience.

For the textbooks, the other professor and I picked out Karl Weber's "Food, Inc.," the companion guide to the movie, and Raj Patel's "Stuffed and Starved." Today, I began re-reading "Food, Inc.," As I did, my thoughts wandered to the nature of progressivism, liberalism, and conservativism, and how these ideas relate to the current food fight between ex-Governor Sarah Palin and First Lady Michelle Obama.

Follow me over the fold for those thoughts.

In the midst of reading editor Karl Weber's description of his experience attending the Slow Food Nation conference in San Francisco over Labor Day Weekend 2008, a paradox struck me. The entire point of the Slow Food Movement is to protect traditional ways of agriculture and food preparation against a massive change to a new way of eating--the American fast food restaurant and the industrial food system that supports it. Isn't defending tradition supposed to be a conservative act, while promoting modernizing change is supposed to be a liberal or progressive act? Yet at least some progressives are lining up behind the Slow Food Movement and related initiatives, while conservatives are attacking the efforts. What's going on here?

Maybe we should step back for a moment and consider exactly what motivates people to be conservative or liberal. I offer two possibilities, one from a conservative's perspective and one from a progressive's perspective.

The conservative position comes from Jerry Pournelle, a science fiction author who Kossack David Brin shakes his head over from time to time.

Why should any Kossack take a conservative science fiction writer who describes his politics as "somewhere to the right of Genghis Khan" seriously? One does if the conservative in question has a Ph.D. in political science and wrote a dissertation entitled "The American political continuum; an examination of the validity of the left-right model as an instrument for studying contemporary American political "isms.""

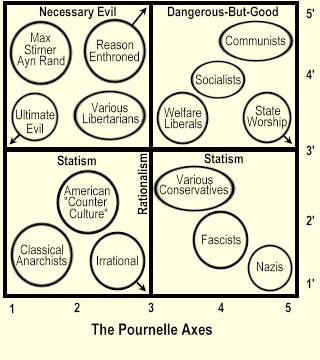

In his disseration, Pournelle came up with the following chart, which is now eponymously termed the Pournelle Chart.

According to Pournelle, the key difference between liberals and conservatives is not the role of government; both groups deep down believe in the power of government. Instead, what separates them is the belief that social problems can be solved by use of reason, which Pournelle calls "rationality." Liberals believe that rationality can be used to perfect society, while conservatives are skeptical of its power. Pournelle, himself a conservative, thus labels conservatives as "irrational" or "anti-rational." Keep this point in mind; it makes for a useful frame to understand the opposition.

Just so that I don’t exclude any Libertarians reading this diary, I’ll add that Pournelle shows that they have a different basis for their political beliefs. They are strongly rational, but have a low belief in state power. So, what would ever unite them with traditional conservatives, who are more irrational and believe in state power? Put the two of them together, and one gets a group of people who display a negative correlation between state power and belief in the usefulness of rationality. Liberals and others on the Left, including the anarchists, on the other hand, show a positive correlation between use of state power and effectiveness of rationality.

According to the Wikipedia article, what Pournelle's chart means is that "those at the top of this axis would tend to discard a traditional custom if they do not understand what purpose it serves (considering it antiquated and probably useless), while those at the bottom would tend to keep the custom (considering it time-tested and probably useful)." Although that might be true for conservatives and progressives in general, it certainly isn't what's going on here. As I pointed out, the progressives are promoting tradition, while the conservatives are supporting changes that are, from the perspectives of efficiency, productivity, and profits (what Joel Salatin, the owner of Polyface Farms calls "bigger, fatter, faster, cheaper"), rational modernizations. Obviously, something else is at play.

For that "something else," I refer you to Michael Alexander, who used to blog on Daily Kos, for the progressive position. In his book Cycles in American Politics: how political, economic and cultural trends have shaped the nation (full disclosure--I was his proofreader for this book and two others), he defines a liberal event or policy as one that satisfies either or both of two criteria. First, it increases partipation in politics and society (the repeal of Don't Ask, Don't Tell and the DREAM Act qualify as liberal here). Second, it improves the economic lot of the "common citizen" or average person (the Lily Ledbetter Act and the Affordable Care Act fit under this criterion). Keep these criteria in mind as another frame to help people understand progressivism.

In contrast, conservativism protects the status quo. It maintains, if not increases, restrictions on political and social participation, and works to the benefit of the already wealthy and against the interests of the poor. Interpreted in this light, the "Food Fight" between the ex-Governor of Alaska and the First Lady makes perfect sense.

And when you look a little deeper, it's not surprising that a crusade seemingly beyond questioning would become a political battle. Interests that might feel threatened by Let's Move include the fast-food industry, agribusiness, soft-drink manufacturers, real estate developers (because suburban sprawl is implicated), broadcasters and their advertisers (of sugary cereals and the like), and the oil-and-gas and automotive sectors (because people ought to walk more and drive less).

Throw in connections to the health-care debate (because preventive services will be key to controlling the epidemic), race (because of differential patterns of obesity) and red state-blue state hostilities (the reddest states tend to be the fattest), and it turns out there are few landmines that Michelle Obama didn't trip by asking us all to shed a few pounds.

The conservatives are indeed protecting the status quo and supporting the already wealthy and powerful.

So, how do these criteria apply to traditions? Progressives will certainly oppose traditions if they impede the political, social, and economic empowerment of common people, while conservatives will uphold traditions that protect the interests of the wealthy and powerful. But as we have seen, the shoes are on the other feet when replacing tradition with rational change. When it comes to change versus tradition, progressives will uphold tradition if it improves the lot of the common person, while conservatives will enact change if it increases the wealth and power of those who already have plenty of both.

Now, how does one synthesize Pournelle and Alexander? For the purposes of argument, I'll accept Pournelle's contention that liberals are greater believers in rationality and progress than conservatives. After all, there is a reason why progressives proudly claimed the term "reality-based community," which was originally meant as an insult. Liberals are also compassionate, and that's what unites Alexander's two criteria for a liberal action. Compassion, displayed as a desire for fairness and harm reduction, is what drives us to increase participation in society and government and improve the lot of our fellow human beings.

A synthesis of the two concepts of liberals and conservatives would result in liberals and progressives being compassionate people who use reason to find ways to improve the common good. In the case of the Slow Food Movement, progressives can easily act as small-c conservatives, as it's more important to us to protect the planet and help the "little guy"--family farms and local small businesses--than it is to overturn tradition. Besides, it helps when traditions have reason and compassion on their side.

As for what this synthesis means about conservatives, I'll let you draw your own conclusions and post them in the comments.

Tips for reason and compassion

There are other ways to analyze the differences between progressives and conservatives than what I've presented here. In particular, I recommend The Authoritarians for a discussion of the two types of authoritarian personalities and how these personalities express themselves in politics, and the work of Jonathan Haidt on the differences in the moral psychology of liberals and conservatives. I've embedded Dr. Haidt's TED talk on the subject below.

Any of you with Daily Kos accounts feel free to click on the link to rec and tip the diary.