Noloholo, Day 51: Impressions

Through the whispering grasses we drive, the afternoon sun browning us to the color of everything else touched by those rays in this landscape, until we too dry and murmur like the rushes in the wind. We’re headed toward Lorkimon, the ridge that rises like a fish’s spine above the Steppe in the distant north. The day had been an unlucky one - one of our staff stepped on a rake and it split his forehead open in a six-stiches wound, Laly tripped and sprained her hand and knee, Paolo broke a toe, Christy’s computer crashed from a virus, we got word of a sick elephant near town, and I’d clumsily shattered both a mug and a water glass on the ground. But by afternoon we are all calmer, and so six of us set off for the ridge. It is a lovely afternoon. We pass by an abandoned boma, the buildings’ mud walls flaking off, the roofs black with mold and disuse and stop for a moment, watching while two jackals trot away from us, their backs black as coal against a pelt of dark honey, their stride keen and graceful. No cattle here, only these lean and lithe wild animals. Then the tsetses are descending and we flee before their drill-bit proboscis can pierce our clothing and flesh. Nonetheless, one gets me, and I know I will itch tomorrow.

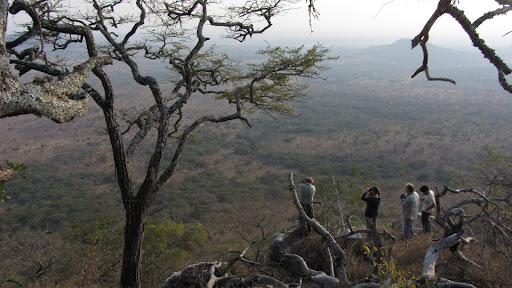

We make the difficult climb up the saddle of Lorkimon in the Land Rover, only needing to get out and push once. I had never before seen a car climb a mountain, and I was amazed when we reached the low ridge of the saddle, finally walking the last hundred feet to our vista point. The view is hazy but all around us are peaks lower than ourselves, rising like gray teeth from the flat jawbones of the earth. The acacias around us have cool, rutted bark; their fingers descend to catch at our skin and clothes. For long moments, the only sound is the breeze setting dead, unfallen leaves against each other.

We sit on the edge of the ridge, dangling our feet into open air and looking outward. The rocks there sparkled with white quartz, marred only with dark soil and prehistoric fungus. Drinking a bottle of rose out of green and white aluminum mugs, we spot wildlife and reminisce. The sun sinks in haze, a scarlet eye casting pink and purple light toward the clouds above. The blanket below us is mottled in shades of washed out green and brown, dusted here and there by the lemon-yellow of a blossoming tree or the bright shade of a fever tree.

It would have been unwise to linger until nightfall, so we pack up and head back just before the sun sinks all the way on Tarangire National Park. The ride down is perhaps more rugged as the one up, thanks to the pull of gravity. As a parallel, imagine the shaking of the Indiana Jones ride at Disneyland, only with less near-death escapes and wild music. Laly points out the wheel tracks we left on our way up. I recall a friend from two years ago, who asked me once while we were hiking, “Do you ever gaze out into the wilderness and see just one subtle trail that you can’t help but follow?” I remember looking at him quizzically, and he tried again, “It’s instinct that draws you forward, because if you look really carefully you don’t really don’t see anything.” Of course, my friend and I were lost at the time, so I doubted his instincts then. We were not lost, as we drove in the dark Tanzanian bush, and I wondered if Laly and Buddy have that instinct that he spoke of.

Anyway, I am following the stars and the setting crescent moon’s cold smile. At one point we startle a herd of impala, who sprang one way and then the other in confusion, as the right-left of our car’s own path crosses them with headlights again and again. In the end they stand still and watch us grumble past them. The rest of the drive to Noloholo, once we reach wheeltracks, is swift and quiet, all of us lost to our own thoughts.

We make the difficult climb up the saddle of Lorkimon in the Land Rover, only needing to get out and push once. I had never before seen a car climb a mountain, and I was amazed when we reached the low ridge of the saddle, finally walking the last hundred feet to our vista point. The view is hazy but all around us are peaks lower than ourselves, rising like gray teeth from the flat jawbones of the earth. The acacias around us have cool, rutted bark; their fingers descend to catch at our skin and clothes. For long moments, the only sound is the breeze setting dead, unfallen leaves against each other.

We sit on the edge of the ridge, dangling our feet into open air and looking outward. The rocks there sparkled with white quartz, marred only with dark soil and prehistoric fungus. Drinking a bottle of rose out of green and white aluminum mugs, we spot wildlife and reminisce. The sun sinks in haze, a scarlet eye casting pink and purple light toward the clouds above. The blanket below us is mottled in shades of washed out green and brown, dusted here and there by the lemon-yellow of a blossoming tree or the bright shade of a fever tree.

It would have been unwise to linger until nightfall, so we pack up and head back just before the sun sinks all the way on Tarangire National Park. The ride down is perhaps more rugged as the one up, thanks to the pull of gravity. As a parallel, imagine the shaking of the Indiana Jones ride at Disneyland, only with less near-death escapes and wild music. Laly points out the wheel tracks we left on our way up. I recall a friend from two years ago, who asked me once while we were hiking, “Do you ever gaze out into the wilderness and see just one subtle trail that you can’t help but follow?” I remember looking at him quizzically, and he tried again, “It’s instinct that draws you forward, because if you look really carefully you don’t really don’t see anything.” Of course, my friend and I were lost at the time, so I doubted his instincts then. We were not lost, as we drove in the dark Tanzanian bush, and I wondered if Laly and Buddy have that instinct that he spoke of.

Anyway, I am following the stars and the setting crescent moon’s cold smile. At one point we startle a herd of impala, who sprang one way and then the other in confusion, as the right-left of our car’s own path crosses them with headlights again and again. In the end they stand still and watch us grumble past them. The rest of the drive to Noloholo, once we reach wheeltracks, is swift and quiet, all of us lost to our own thoughts.