What a manuscript looks like

(A sequel to my previous post)

ILLBETYOUWISHYOUHADNTGIVENUPDIVINATIONNOWDONTYOUHERMIONEASKEDPARVATISMIRKINGITWASBREAKFASTTIMEAFEWDAYSAFTERTHESACKINGOFPROFESSORTRELAWNEYANDPARVATIWASCURLINGHEREYELASHESAROUNDHERWANDANDEXAMININGTHEEFFECTINTHEBACKOFHERSPOONTHEYWERETOHAVETHEIRFIRSTLESSONWITHFIRENZETHATMORNINGNOTREALLYSAIDHERMIONEINDIFFERENTLYWHOWASREADINGTHEDAILYPROPHETIVENEVERREALLYLIKEDHORSES

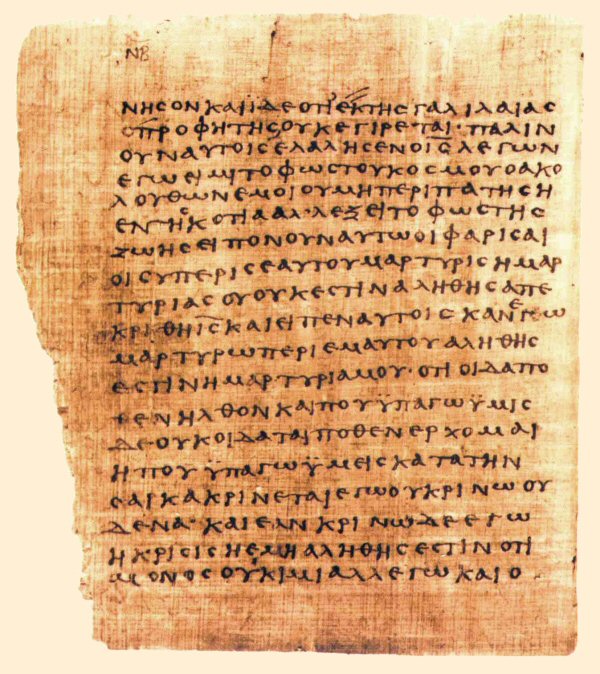

Even worse than this, there might be numerous abbreviations to save even more space and time. Copying manuscripts by hand took a long time and paper was absurdly expensive in the ancient world. A single scroll might cost a year's salary.

Another difficulty is that you have to read the copyist's handwriting, which may be of lesser or greater legibility.

Fortunately, most of us leave the reading of manuscripts to the specialists (called textual critics), who will compare the various manuscripts (a daunting task in the case of Scripture since there are thousands of them) to try to establish as best as they can, through careful reading, what the original text most likely said (no two manuscripts are ever identical since it's impossible to copy something by hand without making mistakes, let alone the changes scribes made deliberately for various reasons). Then they can publish that text with upper and lower case letters, spaces between words, paragraphs, and punctuation (plus a "critical apparatus" that tells you what the more important variant readings are).

Below is a scan of a leaf of Papyrus 66, made around the end of the second century A.D. (making it one of the oldest manuscripts in existence), which contains most of the Gospel of John.

ILLBETYOUWISHYOUHADNTGIVENUPDIVINATIONNOWDONTYOUHERMIONEASKEDPARVATISMIRKINGITWASBREAKFASTTIMEAFEWDAYSAFTERTHESACKINGOFPROFESSORTRELAWNEYANDPARVATIWASCURLINGHEREYELASHESAROUNDHERWANDANDEXAMININGTHEEFFECTINTHEBACKOFHERSPOONTHEYWERETOHAVETHEIRFIRSTLESSONWITHFIRENZETHATMORNINGNOTREALLYSAIDHERMIONEINDIFFERENTLYWHOWASREADINGTHEDAILYPROPHETIVENEVERREALLYLIKEDHORSES

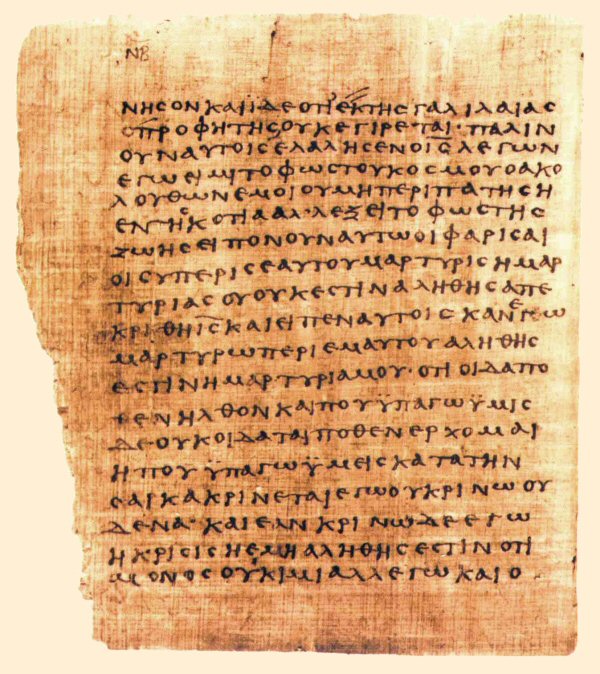

Even worse than this, there might be numerous abbreviations to save even more space and time. Copying manuscripts by hand took a long time and paper was absurdly expensive in the ancient world. A single scroll might cost a year's salary.

Another difficulty is that you have to read the copyist's handwriting, which may be of lesser or greater legibility.

Fortunately, most of us leave the reading of manuscripts to the specialists (called textual critics), who will compare the various manuscripts (a daunting task in the case of Scripture since there are thousands of them) to try to establish as best as they can, through careful reading, what the original text most likely said (no two manuscripts are ever identical since it's impossible to copy something by hand without making mistakes, let alone the changes scribes made deliberately for various reasons). Then they can publish that text with upper and lower case letters, spaces between words, paragraphs, and punctuation (plus a "critical apparatus" that tells you what the more important variant readings are).

Below is a scan of a leaf of Papyrus 66, made around the end of the second century A.D. (making it one of the oldest manuscripts in existence), which contains most of the Gospel of John.