One man's gift eases a struggle

For Cape Verde, he built a school

BRIDGEWATER -- While the chickens scratched and the sweet potatoes grew in the tropical sun of the tiny Cape Verdean farm where Jack Moreira spent much of his childhood, his grandmother taught him how to work, and how to save.

''Djunta tcheu," the grandmother would tell him in her native Criollo. ''Gather a lot."

So he did, as a young man putting away money to come to America. He worked as a new immigrant, working in an East Boston mattress factory. He worked as a janitor on two jobs, depositing the few dollars left over at the end of each week.

He didn't smoke or drink. Both habits might have cost money that could otherwise be saved.

For 34 years in this country, Moreira worked hard. He raised a family. And he never got rich.

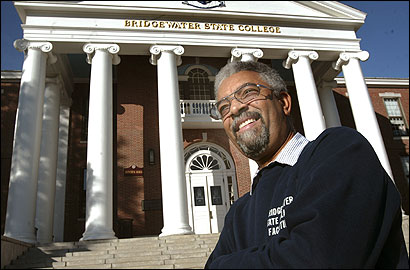

But today, Moreira will receive from Bridgewater State College, where he has been a janitor for 20 years, one of the school's highest honors, its Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Distinguished Service Award.

Amid the struggles of Moreira's life, he did something school officials deemed extraordinary.

Moreira quietly raised money for, and helped to oversee, the construction of a school in the poor town of his youth, to provide education for children who almost certainly wouldn't have had it otherwise.

''It's incredible to have someone who is a maintainer -- not somebody who is wealthy or has access to wealth -- to be able to commit himself to go out and work with others to raise that type of money," said the college president, Dana Mohler-Faria, who is of Cape Verdean descent.

Moreira, 59, is quick to say how good his life has been; he thanks God for what he has. But it could not have been easy.

His mother died before he turned 6. His father worked every day. His grandmother took care of him and two sisters. He went to grammar school, but didn't attend high school because it was on another island in the small nation off the coast of Senagal in West Africa. You had to be rich to take a boat there every day or pay for room and board.

Back then, Jack was Joaquim.

Joaquim worked on the farm to help the family until he turned 20, when he went to Dakar, Senegal, and got work on an oil tanker that traveled to Iraq then to Germany and back.

He saved during the 45-day trips. Eventually, he had enough for a three-month vacation to New England, where he came in 1972 to visit a cousin and uncle. It was a taste of what he could accomplish a bit at a time.

''You want to do something?" said Moreira, in lilting English. ''You got to save your money. ''Djunta tcheu. A little bit here. A little bit there."

Three days after arriving at his Uncle Rio's New Bedford home, Moreira ran into a high school-aged girl named Candida from his island in Cape Verde.

He had seen her back home, but they'd never really talked. For their first date, he brought her a rose and took her to the movies.

When the three months of his vacation were up, he decided he couldn't live without her and resolved to stay. He would marry her two years later.

Moreira at first worked in East Boston, earning $1.80 stuffing mattresses. He lived in an apartment with two others. But it was too far from Candida, so he got a job in Brockton, at the Plymouth Rubber Company, where for 12 years he ran machinery that stirred vats of plastic.

Eventually, Moreira took a janitorial job at Bridgewater State College. It was a friendly place and close to New Bedford, which was home to hundreds of Cape Verdeans. He bought Candida a house in Berkley and applied for US citizenship. He changed his name to Jack to make it easier for his colleagues to pronounce.

At Bridgewater, now, he oversees a small staff of janitors and has daily rounds cleaning; he flicks the lights, checks the trash. He'll go to his tiny basement office and eat a home-packed lunch of rice and beans. It's good work, he said. And it pays for a life that was unattainable in his home country.

''I work with my hands every single day," he said. ''I don't mind. It keeps me busy."

In 1999, Moreira went back to his hometown in Cape Verde.

Much had changed. But he was saddened by some of the things he saw.

''I see all the kids in the streets, barefoot," said Moreira. ''They say they're not in school because it's too far away. They say, 'I can't go because I don't have shoes.' "

It made Moreira think of his first days in America, when he had come home from work exhausted and watched television before bed. Sometimes replays of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s speeches were on.

''I like the way he talks, the way he's walking the street, how he's doing for blacks and African-Americans," he said. ''He changed a lot."

Moreira wanted to change something to. ''I like to do something with my life. I'd like to do something to help my country and my people. Some people say, 'Maybe you'll die hungry,' and that's OK. But if I eat, I like for everybody to eat and be happy."

He thought about it on the six-hour return flight to Boston. He talked to Candida. She suggested a school and a name: Escola Materna Nossa Senhora da Graca.

Moreira talked about it with friends. They threw house parties in Providence and New Bedford.

They charged $120 for a series of four parties in a year and sold plastic bracelets for $5 each. They knocked on the doors of people who hailed from Moreira's home island of Brava.

The group hired a government contractor in Cape Verde. They also hired a Cape Verde lawyer. A pastor whose church is near the school was tapped to supervise the facility after it is built. Relatives and friends in Cape Verde have kept an eye on construction and sent photographs.

The outer shell of the three-story building is complete. American-made windows, doors, and a stove are being shipped this month via cargo ship from Boston.

The group still needs more money to complete the interior and hire administrators and teachers; they are hoping for an Aug. 15 opening.

''We want to give the kids a nice little start in life," said Gabriel N. DaRosa, 60, of North Dartmouth, a Brava native and president of the association. ''We buy the land and start from scratch. We have to buy everything down to the silverware."

The school is fashioned after a category of educational facilities in Cape Verde called Escola Materna.

It will start taking prekindergarteners, and eventually will take children up to 14 years old.

It is a much-needed facility, said Gunga Tavares, an official at the Cape Verdean Consulate.

''The Escola Maternal started as a school to support orphan children," Tavares said. ''Then it grew into a second home with kids who had no home. It's not a school from the public system, but it is recognized. This is obviously a help."

Many of the students at Bridgewater State College are Cape Verdean. So are many employees.

College president Mohler-Faria heard of what Moreira was doing only after running into him in the hallway one day.

''One evening as I was leaving, I stopped to chat with him, and in the course of conversation he told me about this project that I'd followed in the community," said Mohler-Faria, who has now donated to the cause. ''I can attest to the level of poverty there. . . . What this means for them is something absolutely incredible."

Mohler-Faria and others eventually nominated Moreira for the distinguished service award. The school is in the midst of a push to help Cape Verdean students, school officials said.

Moreira's fund-raising seemed to complement that effort.

''We felt like this was a major undertaking and that's why we picked Jack," said Alan Comedy, an award committee member who also oversees affirmative action program efforts at Bridgewater State College.

Moreira gets his award today, during a special breakfast at the school. He maintains he hasn't done anything special.

''It's simple. You have to make do for your country," Moreira said. By Adrienne P. Samuels, Globe Staff | January 16, 2006

Adrienne P. Samuels can be reached at asamuels@globe.com

**I found this interesting and inspirational. We all have to find a way to do our part in each of our communities.**

BRIDGEWATER -- While the chickens scratched and the sweet potatoes grew in the tropical sun of the tiny Cape Verdean farm where Jack Moreira spent much of his childhood, his grandmother taught him how to work, and how to save.

''Djunta tcheu," the grandmother would tell him in her native Criollo. ''Gather a lot."

So he did, as a young man putting away money to come to America. He worked as a new immigrant, working in an East Boston mattress factory. He worked as a janitor on two jobs, depositing the few dollars left over at the end of each week.

He didn't smoke or drink. Both habits might have cost money that could otherwise be saved.

For 34 years in this country, Moreira worked hard. He raised a family. And he never got rich.

But today, Moreira will receive from Bridgewater State College, where he has been a janitor for 20 years, one of the school's highest honors, its Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Distinguished Service Award.

Amid the struggles of Moreira's life, he did something school officials deemed extraordinary.

Moreira quietly raised money for, and helped to oversee, the construction of a school in the poor town of his youth, to provide education for children who almost certainly wouldn't have had it otherwise.

''It's incredible to have someone who is a maintainer -- not somebody who is wealthy or has access to wealth -- to be able to commit himself to go out and work with others to raise that type of money," said the college president, Dana Mohler-Faria, who is of Cape Verdean descent.

Moreira, 59, is quick to say how good his life has been; he thanks God for what he has. But it could not have been easy.

His mother died before he turned 6. His father worked every day. His grandmother took care of him and two sisters. He went to grammar school, but didn't attend high school because it was on another island in the small nation off the coast of Senagal in West Africa. You had to be rich to take a boat there every day or pay for room and board.

Back then, Jack was Joaquim.

Joaquim worked on the farm to help the family until he turned 20, when he went to Dakar, Senegal, and got work on an oil tanker that traveled to Iraq then to Germany and back.

He saved during the 45-day trips. Eventually, he had enough for a three-month vacation to New England, where he came in 1972 to visit a cousin and uncle. It was a taste of what he could accomplish a bit at a time.

''You want to do something?" said Moreira, in lilting English. ''You got to save your money. ''Djunta tcheu. A little bit here. A little bit there."

Three days after arriving at his Uncle Rio's New Bedford home, Moreira ran into a high school-aged girl named Candida from his island in Cape Verde.

He had seen her back home, but they'd never really talked. For their first date, he brought her a rose and took her to the movies.

When the three months of his vacation were up, he decided he couldn't live without her and resolved to stay. He would marry her two years later.

Moreira at first worked in East Boston, earning $1.80 stuffing mattresses. He lived in an apartment with two others. But it was too far from Candida, so he got a job in Brockton, at the Plymouth Rubber Company, where for 12 years he ran machinery that stirred vats of plastic.

Eventually, Moreira took a janitorial job at Bridgewater State College. It was a friendly place and close to New Bedford, which was home to hundreds of Cape Verdeans. He bought Candida a house in Berkley and applied for US citizenship. He changed his name to Jack to make it easier for his colleagues to pronounce.

At Bridgewater, now, he oversees a small staff of janitors and has daily rounds cleaning; he flicks the lights, checks the trash. He'll go to his tiny basement office and eat a home-packed lunch of rice and beans. It's good work, he said. And it pays for a life that was unattainable in his home country.

''I work with my hands every single day," he said. ''I don't mind. It keeps me busy."

In 1999, Moreira went back to his hometown in Cape Verde.

Much had changed. But he was saddened by some of the things he saw.

''I see all the kids in the streets, barefoot," said Moreira. ''They say they're not in school because it's too far away. They say, 'I can't go because I don't have shoes.' "

It made Moreira think of his first days in America, when he had come home from work exhausted and watched television before bed. Sometimes replays of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s speeches were on.

''I like the way he talks, the way he's walking the street, how he's doing for blacks and African-Americans," he said. ''He changed a lot."

Moreira wanted to change something to. ''I like to do something with my life. I'd like to do something to help my country and my people. Some people say, 'Maybe you'll die hungry,' and that's OK. But if I eat, I like for everybody to eat and be happy."

He thought about it on the six-hour return flight to Boston. He talked to Candida. She suggested a school and a name: Escola Materna Nossa Senhora da Graca.

Moreira talked about it with friends. They threw house parties in Providence and New Bedford.

They charged $120 for a series of four parties in a year and sold plastic bracelets for $5 each. They knocked on the doors of people who hailed from Moreira's home island of Brava.

The group hired a government contractor in Cape Verde. They also hired a Cape Verde lawyer. A pastor whose church is near the school was tapped to supervise the facility after it is built. Relatives and friends in Cape Verde have kept an eye on construction and sent photographs.

The outer shell of the three-story building is complete. American-made windows, doors, and a stove are being shipped this month via cargo ship from Boston.

The group still needs more money to complete the interior and hire administrators and teachers; they are hoping for an Aug. 15 opening.

''We want to give the kids a nice little start in life," said Gabriel N. DaRosa, 60, of North Dartmouth, a Brava native and president of the association. ''We buy the land and start from scratch. We have to buy everything down to the silverware."

The school is fashioned after a category of educational facilities in Cape Verde called Escola Materna.

It will start taking prekindergarteners, and eventually will take children up to 14 years old.

It is a much-needed facility, said Gunga Tavares, an official at the Cape Verdean Consulate.

''The Escola Maternal started as a school to support orphan children," Tavares said. ''Then it grew into a second home with kids who had no home. It's not a school from the public system, but it is recognized. This is obviously a help."

Many of the students at Bridgewater State College are Cape Verdean. So are many employees.

College president Mohler-Faria heard of what Moreira was doing only after running into him in the hallway one day.

''One evening as I was leaving, I stopped to chat with him, and in the course of conversation he told me about this project that I'd followed in the community," said Mohler-Faria, who has now donated to the cause. ''I can attest to the level of poverty there. . . . What this means for them is something absolutely incredible."

Mohler-Faria and others eventually nominated Moreira for the distinguished service award. The school is in the midst of a push to help Cape Verdean students, school officials said.

Moreira's fund-raising seemed to complement that effort.

''We felt like this was a major undertaking and that's why we picked Jack," said Alan Comedy, an award committee member who also oversees affirmative action program efforts at Bridgewater State College.

Moreira gets his award today, during a special breakfast at the school. He maintains he hasn't done anything special.

''It's simple. You have to make do for your country," Moreira said. By Adrienne P. Samuels, Globe Staff | January 16, 2006

Adrienne P. Samuels can be reached at asamuels@globe.com

**I found this interesting and inspirational. We all have to find a way to do our part in each of our communities.**