25 Years Ago: My Visit to Neptune

It's been twenty-five years this week since Voyager 2 performed the first-- and, so far, only-- flyby of the planet Neptune.

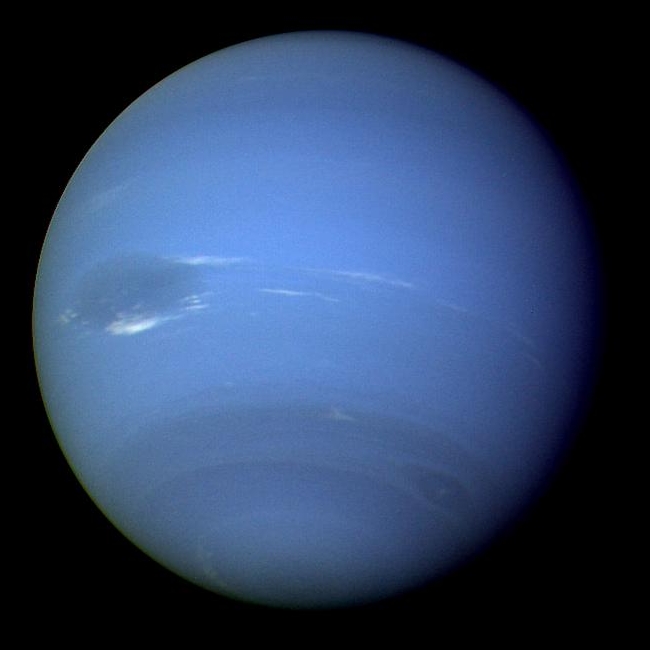

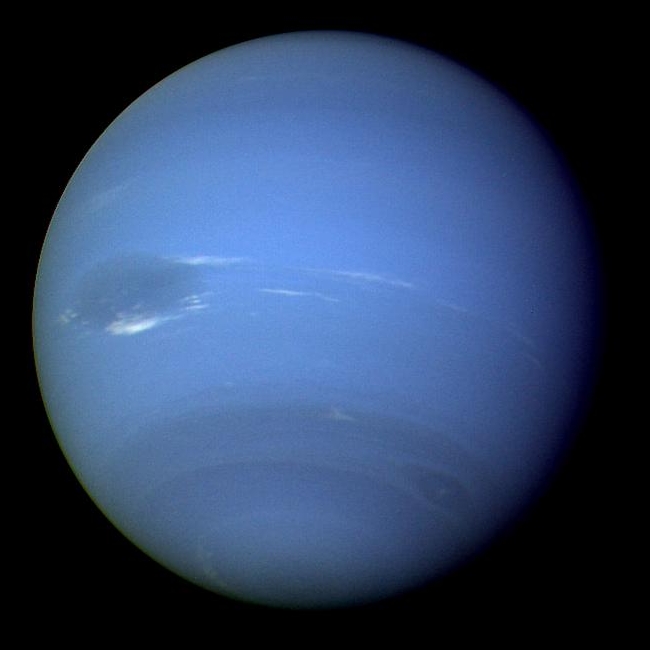

Neptune, with Great Dark Spot and Lesser Dark Spot.

That week I was in Pasadena, playing journalist for a very peculiar news service. It was one of the greatest adventures of my life. Shortly after the encounter, I described my Neptune week in an article entitled I Was a 900-Number Bimbo from Outer Space "Phone Call from a Turquoise Giant."

Diagram of Voyager 2's Neptune and Triton flyby trajectory.

The entire article is long, but I'll give you a few excerpts in the voice of 1989's William S. Higgins.

I'd convinced the people running the National Space Society's Dial-A-Shuttle service that I could absorb NASA's scientific briefings and (quickly!) create clear and concise summaries for the benefit of eager space enthusiasts. I suppose I sounded convincing, because they added me to their team.

Every time a Shuttle mission lifts off (unless it's classified), a team of NSS announcers is ready at the Johnson Space Center in Houston to keep the phone lines hot with information. When there is space-to-ground chatter, callers can hear it live. When astronauts are asleep or busy, or the spacecraft is out of tracking range, Dial-A-Shuttle plays a variety of short taped features which explain aspects of the mission or report on its latest progress. The announcer breaks in every now and then to identify Dial-A-Shuttle, plug NSS, or provide live commentary. Dial-A-Shuttle has been going since STS-7, and has developed a following among space enthusiasts who rely on (900)909-NASA for fresher information and more detail than other news media give. It made sense to try covering the Neptune encounter. But, of course, there are differences. Voyager has no "voice," so there would be no live audio coming from the spacecraft. On the other hand, we could expect much of scientific novelty to be pouring down the data stream in the three days we planned to operate. It's the nature of a flyby mission to report a lot in a short time, so we could provide a service by telling callers about the latest results in the "quick look" science.

Clouds high in Neptune's atmosphere cast shadows on lower layers.

Thursday: The tape wasn't properly recording the press conference, so we had to rely on our own summaries rather than recorded quotes. I was taking notes furiously all through the press conference, and as soon as it was over I started scribbling out a few paragraphs of highlights copy. As I finished a page of copy, I would tear it off my pad and hand it to Peter Kappesser, who would read it in between tapes. Pretty exciting.

By Thursday morning Voyager had not yet passed the "bow shock" of the magnetosphere , somewhat to the surprise of experimenters. I was only vaguely aware of what a bow shock was, but I was about to learn. The frustrated imaging people studying Neptune's clouds were having a lot of trouble measuring wind speeds, because they couldn't find a cloud feature they were sure kept its identity from picture to picture. They were able to see shadows cast by the high white clouds on the lower blue layer, and measured their height to be about 50 kilometers above the blue haze. (Rip. Hand to Peter.) The outer ring had been photographed (well, "imaged") along 90 percent of its length now, and looked indeed like it was a complete 360-degree ring. Two new satellites (1989 N5, 90-kilometer radius, 50,000 kilometers orbital radius, and 1989 N6, 50-kilometer radius, 48,200 kilometers from Neptune's center) were announced. (Rip.) The "old" moon 1989 N1, known for a couple of weeks now, was dark, mottled, and 400 kilometers in diameter, awfully big-bigger than Nereid!-- for something that's so irregular in shape. You expect big objects to be spherical, but N1 is rather heart-shaped.(In case you're wondering, it takes a couple of years to think up names for new satellites, then get the blessing of the International Astronomical Union.) Triton (I suppose you might have called it 1846 N1) still didn't look like much, but we could see a bright pinkish area covering much of the southern hemisphere, and a darker, more bluish area further north. We knew the best was yet to come. (Rip. )

Color mosaic of Triton.

The next day... Sure enough, Friday's images showed that there had once been a lot of activity on the surface of Triton. These were not the best pictures Voyager had taken-recorded color and high-resolution images would be beamed back late Saturday-but they were the first to show a lot of detail. And the detail was spectacular.

Triton's bright region turned out to be a southern polar cap that reflects about 90% of the sunlight reaching it. It covered a variety of terrain, some flat, some rough, and showed mysterious elongated streaks of darker material here and there. The ragged edges of the icecap are being eaten away as Triton enters its summer, and patches of darker surface beneath showed through.

Saturday: Back at the Dial-A-Planet studios, I did more editing, gradually getting better at picking good quotes out of the interview and press-conference tapes and writing introductions for them. I spent a while operating the board, too. I would play a few tapes, then read the ID's: "You're listening to Dial-A-Planet, a service of the National Space Society, coming to you from studios at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. Dial-A-Planet is two dollars for the first minute, and forty-five cents for each minute thereafter." It got easier with practice, and certainly was getting to be fun.

This first appeared in an NSS chapter publication called Spacewatch. It was reprinted in 2011. To celebrate the first Neptunian year since its 1846 discovery, Steven H Silver published an all-Neptune issue of his fanzine Argentus, which included my Turquoise Giant piece.

Neptune, with Great Dark Spot and Lesser Dark Spot.

That week I was in Pasadena, playing journalist for a very peculiar news service. It was one of the greatest adventures of my life. Shortly after the encounter, I described my Neptune week in an article entitled I Was a 900-Number Bimbo from Outer Space "Phone Call from a Turquoise Giant."

Diagram of Voyager 2's Neptune and Triton flyby trajectory.

The entire article is long, but I'll give you a few excerpts in the voice of 1989's William S. Higgins.

I'd convinced the people running the National Space Society's Dial-A-Shuttle service that I could absorb NASA's scientific briefings and (quickly!) create clear and concise summaries for the benefit of eager space enthusiasts. I suppose I sounded convincing, because they added me to their team.

Every time a Shuttle mission lifts off (unless it's classified), a team of NSS announcers is ready at the Johnson Space Center in Houston to keep the phone lines hot with information. When there is space-to-ground chatter, callers can hear it live. When astronauts are asleep or busy, or the spacecraft is out of tracking range, Dial-A-Shuttle plays a variety of short taped features which explain aspects of the mission or report on its latest progress. The announcer breaks in every now and then to identify Dial-A-Shuttle, plug NSS, or provide live commentary. Dial-A-Shuttle has been going since STS-7, and has developed a following among space enthusiasts who rely on (900)909-NASA for fresher information and more detail than other news media give. It made sense to try covering the Neptune encounter. But, of course, there are differences. Voyager has no "voice," so there would be no live audio coming from the spacecraft. On the other hand, we could expect much of scientific novelty to be pouring down the data stream in the three days we planned to operate. It's the nature of a flyby mission to report a lot in a short time, so we could provide a service by telling callers about the latest results in the "quick look" science.

Clouds high in Neptune's atmosphere cast shadows on lower layers.

Thursday: The tape wasn't properly recording the press conference, so we had to rely on our own summaries rather than recorded quotes. I was taking notes furiously all through the press conference, and as soon as it was over I started scribbling out a few paragraphs of highlights copy. As I finished a page of copy, I would tear it off my pad and hand it to Peter Kappesser, who would read it in between tapes. Pretty exciting.

By Thursday morning Voyager had not yet passed the "bow shock" of the magnetosphere , somewhat to the surprise of experimenters. I was only vaguely aware of what a bow shock was, but I was about to learn. The frustrated imaging people studying Neptune's clouds were having a lot of trouble measuring wind speeds, because they couldn't find a cloud feature they were sure kept its identity from picture to picture. They were able to see shadows cast by the high white clouds on the lower blue layer, and measured their height to be about 50 kilometers above the blue haze. (Rip. Hand to Peter.) The outer ring had been photographed (well, "imaged") along 90 percent of its length now, and looked indeed like it was a complete 360-degree ring. Two new satellites (1989 N5, 90-kilometer radius, 50,000 kilometers orbital radius, and 1989 N6, 50-kilometer radius, 48,200 kilometers from Neptune's center) were announced. (Rip.) The "old" moon 1989 N1, known for a couple of weeks now, was dark, mottled, and 400 kilometers in diameter, awfully big-bigger than Nereid!-- for something that's so irregular in shape. You expect big objects to be spherical, but N1 is rather heart-shaped.(In case you're wondering, it takes a couple of years to think up names for new satellites, then get the blessing of the International Astronomical Union.) Triton (I suppose you might have called it 1846 N1) still didn't look like much, but we could see a bright pinkish area covering much of the southern hemisphere, and a darker, more bluish area further north. We knew the best was yet to come. (Rip. )

Color mosaic of Triton.

The next day... Sure enough, Friday's images showed that there had once been a lot of activity on the surface of Triton. These were not the best pictures Voyager had taken-recorded color and high-resolution images would be beamed back late Saturday-but they were the first to show a lot of detail. And the detail was spectacular.

Triton's bright region turned out to be a southern polar cap that reflects about 90% of the sunlight reaching it. It covered a variety of terrain, some flat, some rough, and showed mysterious elongated streaks of darker material here and there. The ragged edges of the icecap are being eaten away as Triton enters its summer, and patches of darker surface beneath showed through.

Saturday: Back at the Dial-A-Planet studios, I did more editing, gradually getting better at picking good quotes out of the interview and press-conference tapes and writing introductions for them. I spent a while operating the board, too. I would play a few tapes, then read the ID's: "You're listening to Dial-A-Planet, a service of the National Space Society, coming to you from studios at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. Dial-A-Planet is two dollars for the first minute, and forty-five cents for each minute thereafter." It got easier with practice, and certainly was getting to be fun.

This first appeared in an NSS chapter publication called Spacewatch. It was reprinted in 2011. To celebrate the first Neptunian year since its 1846 discovery, Steven H Silver published an all-Neptune issue of his fanzine Argentus, which included my Turquoise Giant piece.