Queen Ragnhild's dreams...

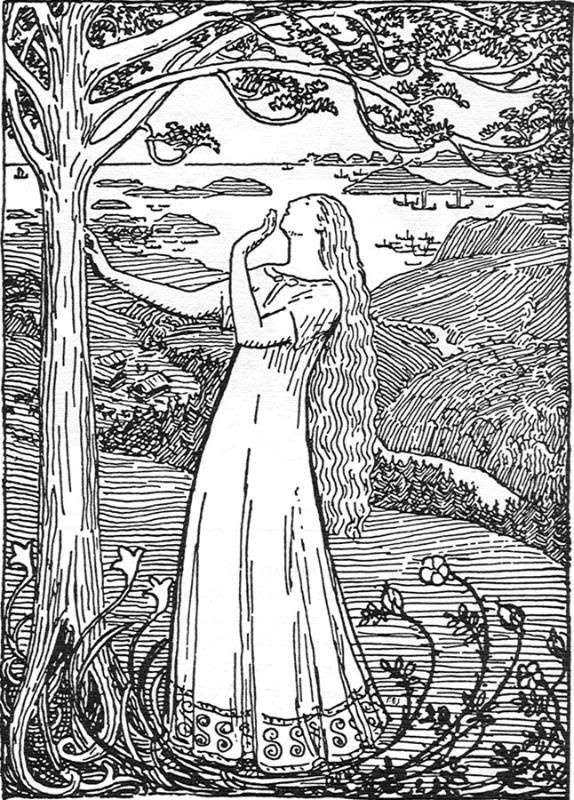

The Sagas tells it like this: The Queen Ragnhild had great dreams, she was a wise woman. Once she dreamt that she was in her garden, and pulled a thorn from her dress. The thorn fell to the ground and a tree started sprouting. At the roots the tree was blood red, the trunk and lower branches were green, but the upper branches were white. The tree was so great and large that it seemed to the Queen it stretched out over all over Norway.

That story appears in Halvdan the Black's Saga, one of the first sagas in Heimskringla, or kringla heimsins meaning the circle of the world. It was written by Snorri Sturlason around 1230 and is a compilation of the Old Norse Kings' Sagas.

During the peak of the Norwegian independence movement, from around 1890 to cessation from Sweden in 1905 - these old sagas became a focal point in the emerging national sentiment. As a result of that a special edition of the saga was published - lavishly illustrated by the who's who of Norwegian artists at the time.

Queen Ragnhild's dream was illustrated by Erik Werenskiold (1855-1936), who was best known for his Realist paintings - but his illustrations for the sagas as well as for the collection of Norwegian fairytales in previous years, has ensured that Werenskiold is best known today as a illustrator of the historical and fantastical.

The story of Ragnhild's dream was pivotal, as the tale was from Snorri intended to be prophetic of the future line of the kings of Norway. The tree that Ragnhild dreams about is a metaphor for the coming royal line - a line she will start by being the mother of Harald the Fairhair, the first king of Norway. But most importantly for Snorri -a devout Christian - this line of kings would lead to St. Olav, the patron saint of Norway and the king.

But whereas Ragnhild's dream is depicted with flowing lines and a clear reference to its Jugend-style aspirations, the saga's darker episodes were also graphically rendered.

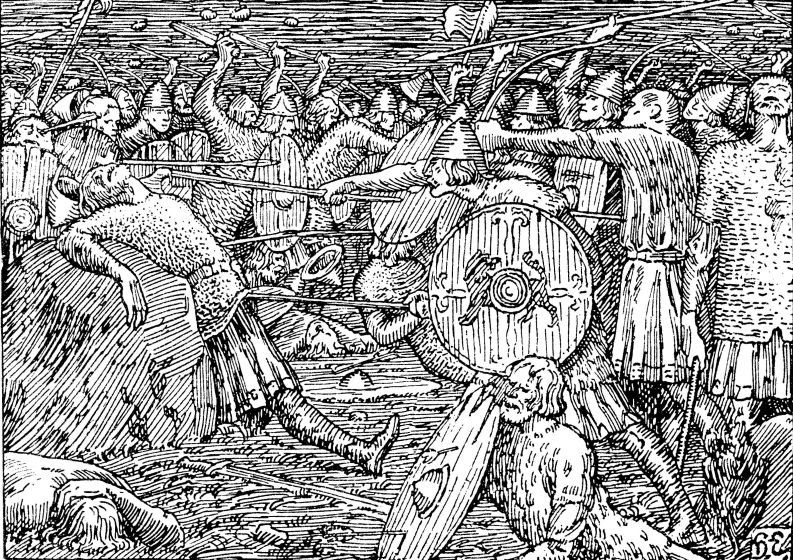

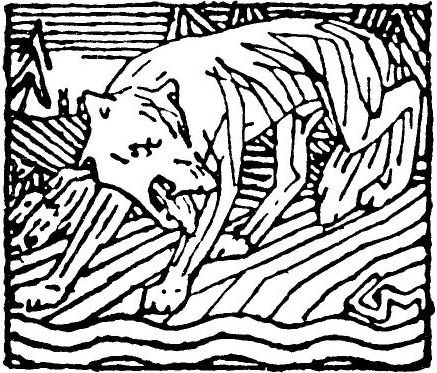

The first saga is the Ynglingatal, and tells of the line of Kings, earls and great men that were the forfathers to the Norse kings. Several of the stories tells of human sacrifice, such as this one of Domalde being bled to death. Or as Snorri recounts it, quoting the older saga created by Tjodolv:

It has happened oft ere now,

That foeman's weapon has laid low

The crowned head, where battle plain,

Was miry red with the blood-rain.

But Domald dies by bloody arms,

Raised not by foes in war's alarms

Raised by his Swedish liegemen's hand,

To bring good seasons to the land

When I was a child this image both scared me and fascinated me at the same time. It is by Erik Werenskiold as well. Another image that has burned itself into my memory was the execution of the seidmenn from Olav Trygvason's saga

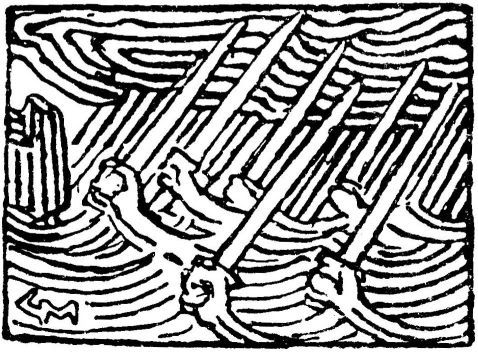

The seidemenn were practitioners of the old Norse religion and used a particular form of magic - seid. This was outlawed by the Christian king, and subsequently the seidemen were put to death - by being tied to poles out on the reefs and left there to drown when the tide came in. That is what this scene by Halfdan Egedius (1877-1899) depicts. Egedius has create a scene that is almost surreal and where it is hard to separate the lines of the ocean with the lines of the sky - in fact they seem to merge, as they would have done for the condemned men gasping ever more for air.

Egedius also made this illustration, which shows the death of Olav Haraldson who will later become St. Olav. He is the one draped across the rock with the spear thrust into his abdomen. Any similarities to Christ on the cross being stabbed by a spear are absolutely intentional.

Another of the artists was Christian Krogh (1852-1925), who did this image from Olav Trygvason's saga, called Gunhild alone on the Orkney Isles after her sons have died. Krogh is considered one of the greatest of Norwegian painters, and was known for his Realist style and his Bohemian way of life.

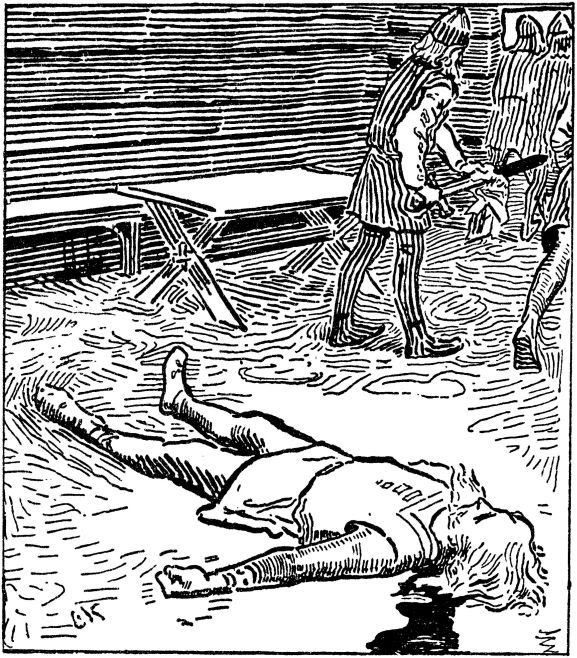

He also illustrated the murder of King Erling from The saga of Earl Haakon. I've always been fascinated by the casual way the murderer wipes of his sword.

But by far my favourite of the bunch was the eccentric Gerhard Munthe (1849-1929), who was highly passionate about the Norse sagas, as well as old folksongs and stories - and who was given the task of creating the chapter headlines, the chapter initials and all the smaller illustrations in the book.

These two wolves are from one of the first saga's, The saga of Harald the Fairhair - so called because he refused to cut his hair before he had united all of Norway under his rule. According to the sagas he managed to do so in 872, and subsequently became Harald I. But Harald was a pagan, and the wolves are Munthe's way of showing the savage, un-Christian times he lived in.

These are from the Saga of Eirik's sons, meaning the story of the sons of Eirik Bloodaxe - himself son of Harald the Fairhair.

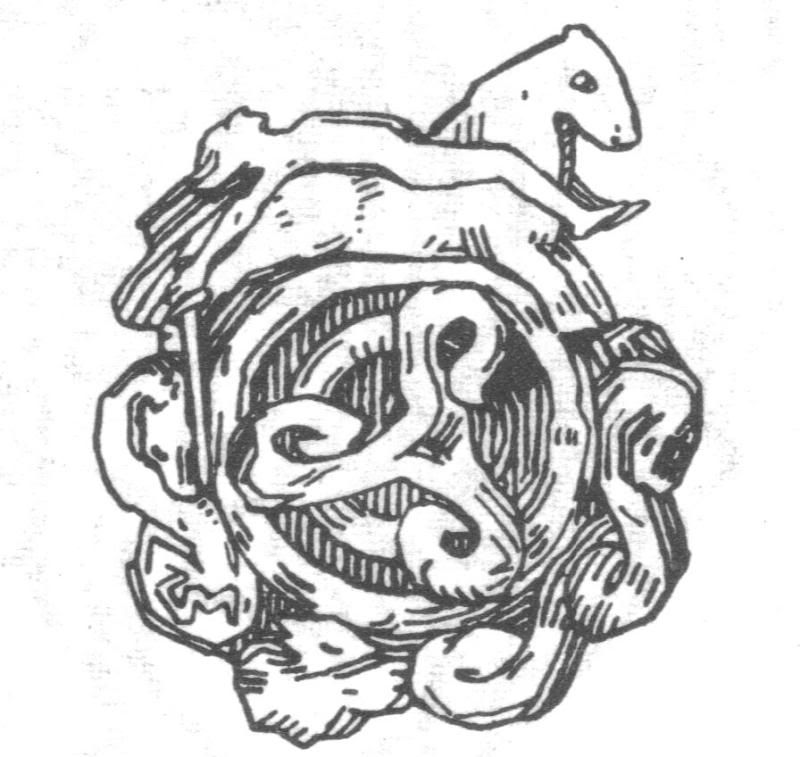

My favourite work of Munthe in connection to the sagas are the illustration of the Ynglingatal, or the first saga. The material in this saga is mythical, with Odin and other gods being referenced constantly.

Munthe wanted to capture what he saw s that saga's archaic and dark feel, and so he created illustrations that were damn near esoteric in their depiction. Gone is the clear realism of Krogh and Werenskiold, and instead the illustrations are small ornamental puzzles.

This is Munthe's chapter header to Ynglingatal, notice again the wolves. The illustrated Old Norse saga became a huge success, breaking all the records and ensuring the sagas a predominate place in Norwegian culture. In fact the illustrations were such a hit, that even today more than a hundred years later all Norwegian editions of these sagas are printed with these illustrations.

In fact the predominance of these illustrations have become so great that they influence everything from dresses, commercials, tourist signs and films. In some way they have, similar to Ragnhild's tree, expanded and covered all of the land.