Research Continued - The History of British Education, Part Three

Boy, I’ll bet you’re all regretting asking for this subject by now...

When we left off, British schools had finally achieved the one thing that schools throughout the world have enjoyed for the past two centuries: unpopularity with the voting masses. Yes, indeed: just like schools of today, parents of the early 19th century believed that in order to improve the schools and make them more responsive to popular opinion, they need to turn to....politics.

Which just goes to show you that we haven’t really gotten smarter over the last few centuries.

And what did the politicians do, when the trusting public asked them to solve the schools? Well...not much. Bills were raised in Parliament...Bills were defeated in Parliament. When reform came, it was at the behest of the headmasters of the “great schools” - Eton, Rugby, and the like, and in particular a headmaster at Rugby by the name of Thomas Arnold, who unlike his predecessors, chose to treat his students like...well...humans. Surprisingly, if you treat sixteen-year-old boys like twenty-six-year-old men, they’ll stop acting like six-year-old infants.

Really, the 19th century seems to be a list of the various Acts and Commissions organized or passed by Parliament dealing with education.

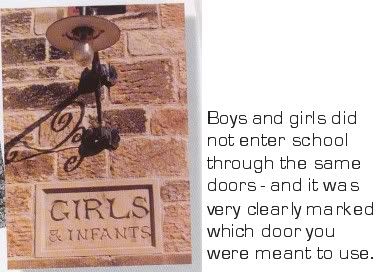

All information was taken from History of Education in Great Britain by S.J. Curtis, 1963. Pictures were taken from various places on the web. I would like to add that apparently, having “Victorian Day” in schools seems to be very popular, as there are lots of sites that exhibit young children wearing pseudo-Victorian garb in an effort to learn what it was like a hundred years ago.

When the government really started paying attention to schools by the mid 19th century, their primary focus was the primary schools: those that gave a basic overview to education. However, in 1861, the Clarendon Commission made a study of higher education and found that while they mainly agreed with the classical education so far available, they felt it lacked flexibility and variety. In short, too few schools taught an acceptable level of mathematics, English, history, geography, or science. The final report written in 1864 stated that on the whole, schools were doing an excellent job of creating a moral fiber in youth, but additional attention to those neglected subjects would not go amiss.

In 1868, the Public Schools Act ignored the entire report and instead focused on administrative matters under the current belief that it really ought to be up to the individual schools to set curriculum. So much for government intervention.

In the end, it didn’t really matter that the government did not press for such reforms; the schools took it upon themselves - at least, those that could manage it - and included courses on French, German, history, physics, chemistry and other such subjects. Additionally, schedules for upper level students became more flexible, allowing those who professed an interest in one subject to take more classes in that vein, and therefore sacrificing subjects in which they perhaps did not do as well.

In 1864, another commission was formed - the Taunton Commission, which was organized to look further into secondary education at a degree with which the earlier commission had not done. What is notable about this commission was that its report - released in 1868 - took into account secondary schools in other countries as well.

The Taunton’s report was not nearly as favorable, particularly in regards to schools in the larger cities. It found that perhaps 5% of the eligible population was attending school at the secondary level, in many cases hampered by the lack of a public school. Half of the secondary schools that did exist were woefully inadequate, being rated as merely superior elementary schools - and further, it was these schools in which girls were admitted. Only one grammar school had managed to retain its superior status and allowed girls to attend, and even then, the girls were kicked out of school at the age of 14, while the boys were kept for another year in preparation for university.

Many of the formerly “free” schools were no longer so, charging for nearly everything, including individual classes. In one case, a commissioner found a school where an entire class of children had not learned to write because their parents had chosen not to pay the writing fee. In another case, he found a class split in two by a sheet hanging down the center of the classroom. On one side were students who paid fees; the other side was for “free” students. The teacher felt it necessary to keep the students separate as the parents of the fee-paying students would complain if their children associated with the others.

A funny tale for those who have dealt with scholarship applications: in 1739, Lady Elizabeth Hastings left an endowment for able students to attend university. “The method of choosing...was curious. Certain rectors and vicars were constituted as examiners and were to meet at the best inn in Aberford, Yorks, before 8am on the Thursday in Whitsun week. The candidates assembled at the same inn the night before, so as to be ready to sit the examination on the following day. The examiners chose the ten best papers and sent them to Queen’s College, where the eight best of the ten were selected. These eight names were written on slips of paper, put into an urn by the Provost, and well shaken up. The first five to be drawn were awarded” the scholarship. Happily, this method was discarded in 1859. (Curtis, 162)

The Commission had drastic suggestions for improvement, but two were the most important. First, they suggested a sort of central authority for each area of England, each with representatives from the community. The authorities would have the power to appoint or dismiss headmasters and wielded control over the school budget. They would also ensure that the schools in their area had distinct purposes - in other words, you wouldn’t find five grammar schools on the eastern half of the county and none on the other.

The second suggestion was an implementation of school fees. After its examination of “free” schools, the commission decided that the concept of free education was obsolete and quite frankly not feasible. They recommended a sliding scale of fees according not to the income of the family, but to the quality of the school. The commission did suggest that a number of scholarships be available, to be awarded by scholarly competition.

The Endowed Schools Act of 1869 put some of these suggestions into operation, and in 1870 some of the first School Boards began to emerge. Some of these were later merged with Charity Commissions in 1874.

But perhaps the biggest immediate influence was the opening of secondary schools to girls - either in brand new complexes for girls only, or by opening slots in existing schools. The benefit of the newly opened schools that while they were modeled on the boys’ grammar schools, they took into account new recommendations for a variety of subjects, and in addition to Latin, Greek, Literature and the rest, they also offered French, history and natural sciences. Many leaders of the day persisted in insisting that girls were equally as intelligent as boys and ought to be allowed to sit the same examinations on the same terms. In 1869 girls were invited to sit the London matriculation exam (although it would be another eleven years before girls were actually admitted as degree candidates). In 1865, girls were first allowed to sit for the Cambridge local examinations, although it wasn’t for another sixty years before girls would be allowed to receive degrees in 1921.

Mind that this period was also when most schools opened officially anyway - and instead of being supported by the church, they were the direct result of the Act of 1869 and thus were funded by the government. These schools were called “council schools” and they remained subject to the whims of the government officials who had implemented the changes that inspired them.

We discussed before how many students were unable to take advantage of school not only because they could not afford it, but because their families could not afford for them not to work. Lord Sandon’s Act of 1876 was one of the first acts to actually discuss this issue by setting a schedule of penalties against parents who did not in some way ensure that their children received an adequate education in the three Rs. It also stated that employers were not allowed to hire children younger than ten, and further that children between ten and fourteen must attend school at least half-time. Of course, there were loopholes; if a child passed a certain standard, he was exempted from further attendance. Mr. Mundella’s Act in 1880 allowed for a child of 13 to quit school entirely based on his or her attendance, and not whether or not she or he could pass a standard.

In 1893, the school leaving age was set at eleven years old. In 1899, it was raised to twelve. Think for a moment now - can you imagine leaving school at the age of eleven or twelve? Yeah, me neither!

A story about teachers in the 1880s shows that teachers then had it just as bad as those today - in very different ways. One head teacher’s diary gives a very clear view of daily life in a rural school:

1884. Feb 1. Mrs. Be called and was exceedingly abusive about her boy being kept back to do his work. She went so far as to threaten personal violence with a dinner fork which she kept in her hand. The boy was suspended till apology was made by mother.

1883. June 1. Organized a systematic cleaning of all dirty boys in the school. 80 cleaned this morning and 60 cleaned this afternoon.

1884. Nov 18. A note was sent enquiring as to the reason for a boy’s absence. The reply was, “Fetching the gin and no boots.”

The 1890s brought further inspection and change within the school system, including a focus on physical education. I don’t know about you all, but I hated P.E. as a child. Of course, physical education was much different when it was first introduced, mostly because it wasn’t all about baseball and football and volleyball and other sorts of ball - in fact, it had nothing to do with ball at all: P.E. was given in the form of military-style marching. Both boys and girls were instructed in military formations and exercises, and the goal was not so much physical development as instilling a sense of discipline and obedience.

There had been a national movement to implement football clubs within the schools since the 1880s, however, and by 1895 every important town had school organizations for both football and cricket. (Note to the Americans, although really you ought to know this anyway: “football”, unless you’re in the U.S., actually is soccer.) Cricket was a little more difficult to organize owing to the lack of appropriate grounds, but most park pitches were set aside for school use on Saturday mornings. Eventually, swimming and rugby (think American football without the pads) were made available as part of a regular school course as well.

Libraries also become more widespread in the 1890s - by 1894 there were sixty-three libraries specifically for children. Many existing libraries set up rooms for youngsters as well, and in some schools, children were required to be reading a library book at all times.

Basic school supplies also made an appearance. Blackboards, wall maps, atlases, and dual desks (as opposed to the earlier long, backless benches) began to appear in classrooms.

(Mind that all of these improvements and revisions dealt only with the average child. Children who had special educational or developmental needs, children who were orphans or too poor to afford the basics of schooling, or children who were delinquents had their own issues which required special attention. And while those attentions were paid, I’m not going to highlight them here.)

The last act we’ll discuss here is the Education Act of 1902, which formally set up Local Education Authorities (commonly abbreviated as L.E.A.s). LEAs were allowed to raise funding for the schools, ensuring that the budget would remain under public control. The LEAs allowed membership for teachers and women as well as men. Finally, the LEAs were given authority to dismiss not only headmasters, but individual teachers as well.

The act also set that religious instruction in council schools should be non-denominational, and that parents were given the ability to keep their children out of religious instruction without any penalty. At the same time, it allocated a place in the system for denominational schooling and decreed that schools funded by the church still were subject to the same regulations as the council schools.

The one thing the act did not do was create a smooth flow from elementary education to secondary education. As the leaving age was still twelve, most students left school when they concluded their primary education. There was no drive to convince children to stay in school for a longer period of time, and the act made no motion to do so. Secondary school was still very much out of reach - and not even a consideration - for most people. Part of this was likely due to the fact that you couldn’t even enter the secondary school system without passing the Common Entrance Exam, created in 1903.

So there you have it. If you were a student in Britain at the turn of the century, you were mostly likely middle class. You learned Latin and history and maybe mathematics. Your classes were conducted in English and you had physical exercises that involved marching back and forth across the field. You probably left school at the age of 12 and went to find a job.

Tune in next time, in what will (I promise) be the final episode, when we see how the world of education in 1902 turned into the world of education in 1948. (Yeah, I never thought we’d get there, either.)

When we left off, British schools had finally achieved the one thing that schools throughout the world have enjoyed for the past two centuries: unpopularity with the voting masses. Yes, indeed: just like schools of today, parents of the early 19th century believed that in order to improve the schools and make them more responsive to popular opinion, they need to turn to....politics.

Which just goes to show you that we haven’t really gotten smarter over the last few centuries.

And what did the politicians do, when the trusting public asked them to solve the schools? Well...not much. Bills were raised in Parliament...Bills were defeated in Parliament. When reform came, it was at the behest of the headmasters of the “great schools” - Eton, Rugby, and the like, and in particular a headmaster at Rugby by the name of Thomas Arnold, who unlike his predecessors, chose to treat his students like...well...humans. Surprisingly, if you treat sixteen-year-old boys like twenty-six-year-old men, they’ll stop acting like six-year-old infants.

Really, the 19th century seems to be a list of the various Acts and Commissions organized or passed by Parliament dealing with education.

All information was taken from History of Education in Great Britain by S.J. Curtis, 1963. Pictures were taken from various places on the web. I would like to add that apparently, having “Victorian Day” in schools seems to be very popular, as there are lots of sites that exhibit young children wearing pseudo-Victorian garb in an effort to learn what it was like a hundred years ago.

When the government really started paying attention to schools by the mid 19th century, their primary focus was the primary schools: those that gave a basic overview to education. However, in 1861, the Clarendon Commission made a study of higher education and found that while they mainly agreed with the classical education so far available, they felt it lacked flexibility and variety. In short, too few schools taught an acceptable level of mathematics, English, history, geography, or science. The final report written in 1864 stated that on the whole, schools were doing an excellent job of creating a moral fiber in youth, but additional attention to those neglected subjects would not go amiss.

In 1868, the Public Schools Act ignored the entire report and instead focused on administrative matters under the current belief that it really ought to be up to the individual schools to set curriculum. So much for government intervention.

In the end, it didn’t really matter that the government did not press for such reforms; the schools took it upon themselves - at least, those that could manage it - and included courses on French, German, history, physics, chemistry and other such subjects. Additionally, schedules for upper level students became more flexible, allowing those who professed an interest in one subject to take more classes in that vein, and therefore sacrificing subjects in which they perhaps did not do as well.

In 1864, another commission was formed - the Taunton Commission, which was organized to look further into secondary education at a degree with which the earlier commission had not done. What is notable about this commission was that its report - released in 1868 - took into account secondary schools in other countries as well.

The Taunton’s report was not nearly as favorable, particularly in regards to schools in the larger cities. It found that perhaps 5% of the eligible population was attending school at the secondary level, in many cases hampered by the lack of a public school. Half of the secondary schools that did exist were woefully inadequate, being rated as merely superior elementary schools - and further, it was these schools in which girls were admitted. Only one grammar school had managed to retain its superior status and allowed girls to attend, and even then, the girls were kicked out of school at the age of 14, while the boys were kept for another year in preparation for university.

Many of the formerly “free” schools were no longer so, charging for nearly everything, including individual classes. In one case, a commissioner found a school where an entire class of children had not learned to write because their parents had chosen not to pay the writing fee. In another case, he found a class split in two by a sheet hanging down the center of the classroom. On one side were students who paid fees; the other side was for “free” students. The teacher felt it necessary to keep the students separate as the parents of the fee-paying students would complain if their children associated with the others.

A funny tale for those who have dealt with scholarship applications: in 1739, Lady Elizabeth Hastings left an endowment for able students to attend university. “The method of choosing...was curious. Certain rectors and vicars were constituted as examiners and were to meet at the best inn in Aberford, Yorks, before 8am on the Thursday in Whitsun week. The candidates assembled at the same inn the night before, so as to be ready to sit the examination on the following day. The examiners chose the ten best papers and sent them to Queen’s College, where the eight best of the ten were selected. These eight names were written on slips of paper, put into an urn by the Provost, and well shaken up. The first five to be drawn were awarded” the scholarship. Happily, this method was discarded in 1859. (Curtis, 162)

The Commission had drastic suggestions for improvement, but two were the most important. First, they suggested a sort of central authority for each area of England, each with representatives from the community. The authorities would have the power to appoint or dismiss headmasters and wielded control over the school budget. They would also ensure that the schools in their area had distinct purposes - in other words, you wouldn’t find five grammar schools on the eastern half of the county and none on the other.

The second suggestion was an implementation of school fees. After its examination of “free” schools, the commission decided that the concept of free education was obsolete and quite frankly not feasible. They recommended a sliding scale of fees according not to the income of the family, but to the quality of the school. The commission did suggest that a number of scholarships be available, to be awarded by scholarly competition.

The Endowed Schools Act of 1869 put some of these suggestions into operation, and in 1870 some of the first School Boards began to emerge. Some of these were later merged with Charity Commissions in 1874.

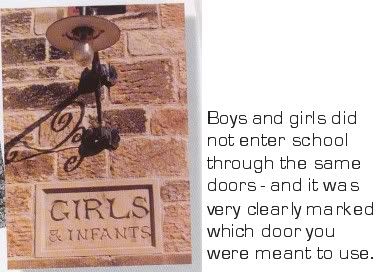

But perhaps the biggest immediate influence was the opening of secondary schools to girls - either in brand new complexes for girls only, or by opening slots in existing schools. The benefit of the newly opened schools that while they were modeled on the boys’ grammar schools, they took into account new recommendations for a variety of subjects, and in addition to Latin, Greek, Literature and the rest, they also offered French, history and natural sciences. Many leaders of the day persisted in insisting that girls were equally as intelligent as boys and ought to be allowed to sit the same examinations on the same terms. In 1869 girls were invited to sit the London matriculation exam (although it would be another eleven years before girls were actually admitted as degree candidates). In 1865, girls were first allowed to sit for the Cambridge local examinations, although it wasn’t for another sixty years before girls would be allowed to receive degrees in 1921.

Mind that this period was also when most schools opened officially anyway - and instead of being supported by the church, they were the direct result of the Act of 1869 and thus were funded by the government. These schools were called “council schools” and they remained subject to the whims of the government officials who had implemented the changes that inspired them.

We discussed before how many students were unable to take advantage of school not only because they could not afford it, but because their families could not afford for them not to work. Lord Sandon’s Act of 1876 was one of the first acts to actually discuss this issue by setting a schedule of penalties against parents who did not in some way ensure that their children received an adequate education in the three Rs. It also stated that employers were not allowed to hire children younger than ten, and further that children between ten and fourteen must attend school at least half-time. Of course, there were loopholes; if a child passed a certain standard, he was exempted from further attendance. Mr. Mundella’s Act in 1880 allowed for a child of 13 to quit school entirely based on his or her attendance, and not whether or not she or he could pass a standard.

In 1893, the school leaving age was set at eleven years old. In 1899, it was raised to twelve. Think for a moment now - can you imagine leaving school at the age of eleven or twelve? Yeah, me neither!

A story about teachers in the 1880s shows that teachers then had it just as bad as those today - in very different ways. One head teacher’s diary gives a very clear view of daily life in a rural school:

1884. Feb 1. Mrs. Be called and was exceedingly abusive about her boy being kept back to do his work. She went so far as to threaten personal violence with a dinner fork which she kept in her hand. The boy was suspended till apology was made by mother.

1883. June 1. Organized a systematic cleaning of all dirty boys in the school. 80 cleaned this morning and 60 cleaned this afternoon.

1884. Nov 18. A note was sent enquiring as to the reason for a boy’s absence. The reply was, “Fetching the gin and no boots.”

The 1890s brought further inspection and change within the school system, including a focus on physical education. I don’t know about you all, but I hated P.E. as a child. Of course, physical education was much different when it was first introduced, mostly because it wasn’t all about baseball and football and volleyball and other sorts of ball - in fact, it had nothing to do with ball at all: P.E. was given in the form of military-style marching. Both boys and girls were instructed in military formations and exercises, and the goal was not so much physical development as instilling a sense of discipline and obedience.

There had been a national movement to implement football clubs within the schools since the 1880s, however, and by 1895 every important town had school organizations for both football and cricket. (Note to the Americans, although really you ought to know this anyway: “football”, unless you’re in the U.S., actually is soccer.) Cricket was a little more difficult to organize owing to the lack of appropriate grounds, but most park pitches were set aside for school use on Saturday mornings. Eventually, swimming and rugby (think American football without the pads) were made available as part of a regular school course as well.

Libraries also become more widespread in the 1890s - by 1894 there were sixty-three libraries specifically for children. Many existing libraries set up rooms for youngsters as well, and in some schools, children were required to be reading a library book at all times.

Basic school supplies also made an appearance. Blackboards, wall maps, atlases, and dual desks (as opposed to the earlier long, backless benches) began to appear in classrooms.

(Mind that all of these improvements and revisions dealt only with the average child. Children who had special educational or developmental needs, children who were orphans or too poor to afford the basics of schooling, or children who were delinquents had their own issues which required special attention. And while those attentions were paid, I’m not going to highlight them here.)

The last act we’ll discuss here is the Education Act of 1902, which formally set up Local Education Authorities (commonly abbreviated as L.E.A.s). LEAs were allowed to raise funding for the schools, ensuring that the budget would remain under public control. The LEAs allowed membership for teachers and women as well as men. Finally, the LEAs were given authority to dismiss not only headmasters, but individual teachers as well.

The act also set that religious instruction in council schools should be non-denominational, and that parents were given the ability to keep their children out of religious instruction without any penalty. At the same time, it allocated a place in the system for denominational schooling and decreed that schools funded by the church still were subject to the same regulations as the council schools.

The one thing the act did not do was create a smooth flow from elementary education to secondary education. As the leaving age was still twelve, most students left school when they concluded their primary education. There was no drive to convince children to stay in school for a longer period of time, and the act made no motion to do so. Secondary school was still very much out of reach - and not even a consideration - for most people. Part of this was likely due to the fact that you couldn’t even enter the secondary school system without passing the Common Entrance Exam, created in 1903.

So there you have it. If you were a student in Britain at the turn of the century, you were mostly likely middle class. You learned Latin and history and maybe mathematics. Your classes were conducted in English and you had physical exercises that involved marching back and forth across the field. You probably left school at the age of 12 and went to find a job.

Tune in next time, in what will (I promise) be the final episode, when we see how the world of education in 1902 turned into the world of education in 1948. (Yeah, I never thought we’d get there, either.)