Recreating Saint Petersburg's nightlife in Constantinople (1920)

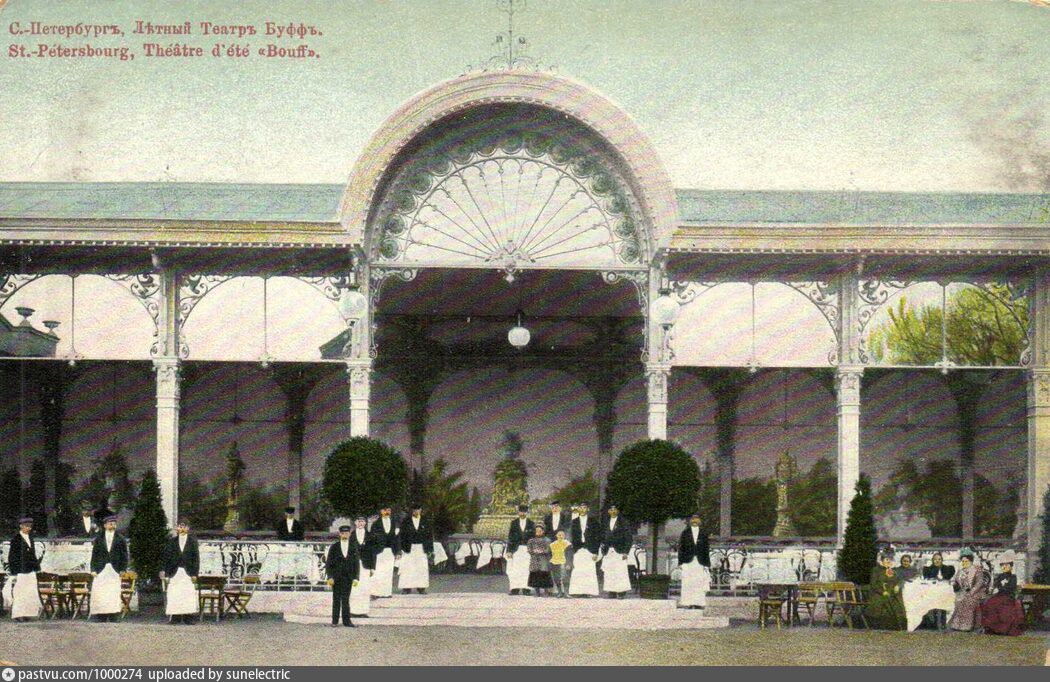

"...At the edge of the city, almost outside of it, there was a suburb intersected by a long street called Şişli, and this is where a certain Thomas, aka the Black Russian, opened his Stella Cabaret. The public liked it, and the business was good. When I kicked out Isa Kremer from my cabaret, she started to perform for Thomas. Nearby, a bit closer to the city, there was a small and tangled garden, completely abandoned. So Nastya Poliakova and I rented it and started to work on it; the talented theatre manager Alexandre Polonsky and the decorator Nepokoynitsky helped us. Together, we turned this wasteland into a miniature copy of Saint Petersburg's open air theatre Bouff. We had filigree pavilions and fancy gravel on the walkways. The garden was flooded with electric lights, and this red glow could be seen from afar. Thomas's Stella paled in comparison. On their way from the city, the public saw our place first - it was named Strelna - and they went in, completely forgetting about Stella. For garçons we had society ladies and highborn aristocrats - not because this was our policy, but because such were the things in those days.

Our cabaret was more than thriving. We were in a state of bliss. Even little hiccups with the management did little to damage our cash flow. For instance, I allowed my accompanist Sasha Makaroff to be the bartender's assistant, and they conspired to sell their own liquor, pocketing the money and leaving my bottles untouched. I did not mind. But then the occupational forces instituted a curfew and fined the establishments that stayed open past a certain hour. Of course, we ignored the rules and partied until the break of dawn, so someone reported us. I think it was Isa Kremer, who was then performing at Thomas's Stella. We were ordered to close for eight days, and that was devastating. Our shining spinning wheel came to a grinding halt. Crowds of revelers drove past our dark and quiet garden and headed straight to the Stella. Yes, the customers still liked us and offered their sympathies, but what of it? To save face, we told everyone we were working on some grandiose renovation, preparing something that would make the entire Constantinople gasp.

It was not a lie. We were, in fact, preparing a new performance - the Helen of Troy, with new Max Reinhardt-style tricks. Helen's palanquin was brought to the stage by real Africans, some colossal guys from Nubia. Agamemnon rode on his donkey, while the King Menelaus, whom Polonsky played himself, arrived on the back of a traditional Turkish hamal porter. Add to this two orchestras, the corps de ballet, the choir, the original staging, the interaction with the public, the stunning lighting design, the colorful costumes - and you will understand what success our Helen of Troy enjoyed. This was out last burst, our final beam of sunlight shining through the ominous stormy clouds.

The income tax did us in. The Turkish bureaucrats, who dutifully enjoyed our hospitality every night, kept assuring us that tax law meant nothing, that it was just print on paper, and that they would make sure we would not have to pay anything. And we believed them. But one gloomy morning I received a formal letter with a request to pay 5,000 Turkish lira in taxes, or face jail time. The Turks are wonderful people, but their prisons are terrible. I'd have to suffer extra for being a Greek citizen. I was not thrilled at the prospect of spending time behind the bars, and it was equally impossible to pay so much cash - no more possible than to swallow Hagia Sophia. Choosing between the two, I chose the third: I had my last breakfast at the Tokatlian, and at one in the afternoon I was already on the deck of the Italian cruiser Cleopatra, protected by its extraterritoriality..."

Yuri Morfessi on his sojourn in Istanbul in 1920, translated from Zhizn, Lubov, Szena, Vospominania russkogo bayana (Life, Love, Stage: Memoirs of the Russian accordion player) (1931).