(no subject)

So, I saw I'm Not There today, and was thoroughly impressed. I'm a bit too tired to write about it tonight, but I look forward to getting my thoughts down on paper. I'll say it did everything I had hoped for, and avoided all the pitfalls of biopics I dreaded.

"It's Like you've got yesterday, today and tomorrow in the same room. There's no telling what might happen."

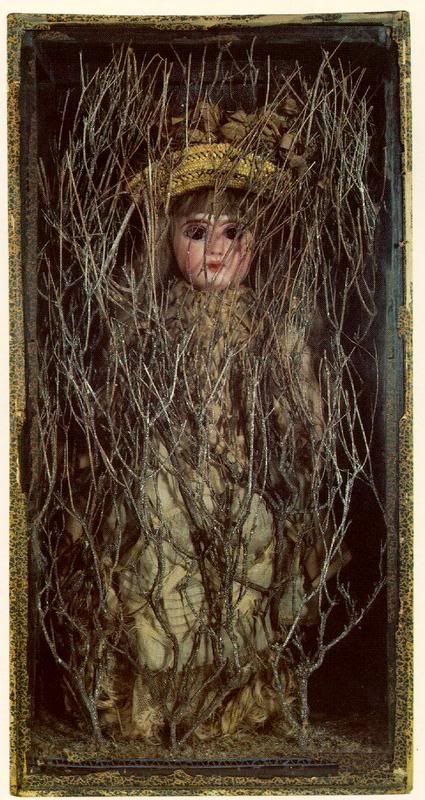

I'm reading a biography on Joseph Cornell by Deboroh Solomon. It's called Utopia Parkway and I used it as a source for a study of Cornell's piece Untitled (Bebe Marie) for my art history class. The humble, melancholic feeling to his work has always kept his work close to my heart...

This piece, from the early 1940s, is an early example of Cornell’s box collages. Assemblages of old Victorian-era simulacrum, these boxes are a kind of highly personalized surrealism, not by a dynamic absurdity, but rather a kind of whimsical aesthetic that had a deep melancholic undertow. Nowhere is this more apparent in Cornell’s oeuvre than this early box that contains a doll standing behind sticks that encompass the whole front of the frame. The bottom of the box is covered in a mossy grass that further brings about a sense of elegiac wonder in the viewer.

The composition of this, and many of his other boxes foretells what would become installation art, and, quite possibly, the emergence of what has been deemed locative art . This piece in particular is founded largely on the evocation of a sense of place, a lost time someplace during the mid-19th century, when women wore the same kind of antiquated dress the doll has on; a long flowing gown, with a large hat to cover flowing blonde hair. According to Deborah Solomon the work “takes its name from the pretty, apple-cheeked Victorian doll-a real doll with blond tresses and a straw hat…” (153). Here, Cornell not only idealizes place and time, but beauty as well. For he made many of his boxes for young girls and older women who he was attracted to from a far.

The girl in this box then takes on a kind of model, in the way that it dominates the ‘scene’ of the box. In a kind of reverse voyeurism, Cornell has set the gazing eyes of the doll coming out of the tiny branches, partly masking the face of the girl in the shadow of woods. This creates a sense of disconnection between viewer and object that is found most commonly among Constructivists of the early 20th century. Cornell’s personalized constructivism is, like his own surrealism, all his own.

Cornell transforms the doll into a symbol of female as object, not a female as sexual object, but rather a female as a prudish object. The idealized Victorian form ‘hidden’ behind the trees then has less to do with the Surrealists of the time, whose main obsession were the psychosexual tendencies in man, than with Cornell’s own celibacy. The tree branches in this context then represent barriers separating the desired from the desiring. The Victorian-era clothing further suggests a conservative aesthetic that is more highly valued in the majority of Cornell’s work, but this isn’t simplistic nostalgia, but rather a haunting construction of remnant semiotic codes left over from generations past. The doll is not a an object presented as is, as are many of his other ‘ready-mades’ from his oeuvre, it is a highly personalized image that is being shielded and in a way protected from the newer societal constructs of the present.

At the same time his works bear an unmistakable stamp of the early to mid 20th century and would rarely be taken for anything other than the work of this master artisan. I’m reminded of Joseph Campbell’s immortal words in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, “the crux of the curious difficulty lies in the fact that our conscious views of what life ought to be seldom correspond to what life really is” (121). This difficulty is man’s attempt to traverse through the various courses of life, all the while trying to do battle between reality and another kind of reality that arises from certain primal needs and desires that cannot be satiated by the first kind of reality. Cornell’s work resides in the latter category, but I hesitate to label it simple fantasy fulfillment, for what a dark and dreary fantasy that might be. Instead I see Untitled (Bebe Marie) as a struggle with passion, again not simply of the surrealist sexual tendencies; a passion for connection through the constricted ‘branches’ of life, that often obscure what the reality of a goal might actually be.

For this piece the viewer becomes tied to looking beyond the sticks covering the doll, instead trying to make out the total shape of the doll as if the brush didn’t impede the view. This is what most of man’s journey consists of, trying to get past the surface level codes, signs and visual/aural games that are so often heaved on top of us. Further autobiographical readings imply that Cornell was trying to get at the heart of women. In taking such a reading the work comes of as a bit creepy, yet there remains an undeniably endearing quality to the piece, for Cornell studied women his entire life, offering up many a work in tribute to famous starlets and long since deceased dancers. He wouldn’t come into romantic relationships until the last decade of his life (Solomon). The everlasting gaze of the doll then, represents a promise for romantic vindication, an elegiac letter from the heart to an unknown love.

The readings become further complicated by one’s own proclivities towards the heartbreaking of dour. I chose the path of Neo-Romanticism in my description of desire for future loves while someone else more schooled in Surrealism and the Dadaists might read it as a deconstruction of form as it relates to societal models. This provides ample evidence that this piece, and many of his other shadow boxes have attained a kind of sui generis position in the art world, admired by many, rarely for the same reasons, never quite fitting in to one camp or another.

Cornell’s Untitled (Bebe Marie) is a work that expresses personal obsessions through collective cultural images that turns the viewer in on himself and his society. It is one piece in a continued study of desire, anachronisms, artistic form and repetition. Where would Pop Art be without him?

I also saw Cassavetes Love Streams at the BAMrose a few days ago and was pleasantly surprised by its density and oneiric qualities. It possesses a magic that I think is only matched by A Woman Under the Influence. It doesn't seem as well composed as that film or his other masterwork Faces, but what distracting tendencies it holds in its messy composition, it more than makes up for in its moment by moment exploration of familial relationships and the hardships of love an passion. It always has amazed me how Cassavetes can be so affecting on our emotions without ever falling into sentimentalism. It's a shame it's not out on DVD.

Happy Thanksgiving all.

"It's Like you've got yesterday, today and tomorrow in the same room. There's no telling what might happen."

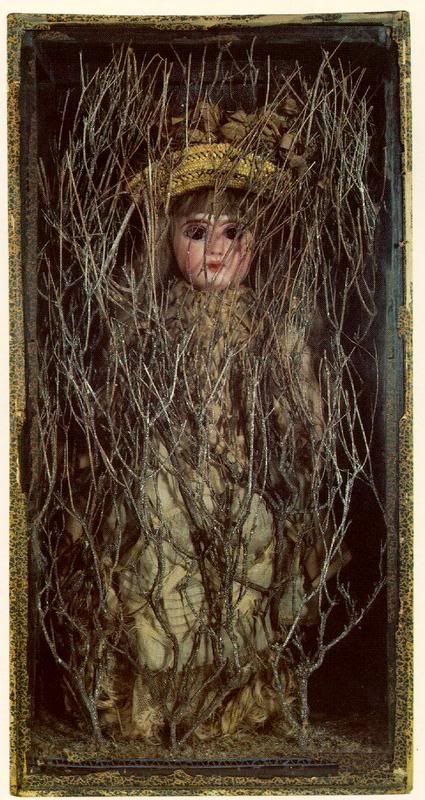

I'm reading a biography on Joseph Cornell by Deboroh Solomon. It's called Utopia Parkway and I used it as a source for a study of Cornell's piece Untitled (Bebe Marie) for my art history class. The humble, melancholic feeling to his work has always kept his work close to my heart...

This piece, from the early 1940s, is an early example of Cornell’s box collages. Assemblages of old Victorian-era simulacrum, these boxes are a kind of highly personalized surrealism, not by a dynamic absurdity, but rather a kind of whimsical aesthetic that had a deep melancholic undertow. Nowhere is this more apparent in Cornell’s oeuvre than this early box that contains a doll standing behind sticks that encompass the whole front of the frame. The bottom of the box is covered in a mossy grass that further brings about a sense of elegiac wonder in the viewer.

The composition of this, and many of his other boxes foretells what would become installation art, and, quite possibly, the emergence of what has been deemed locative art . This piece in particular is founded largely on the evocation of a sense of place, a lost time someplace during the mid-19th century, when women wore the same kind of antiquated dress the doll has on; a long flowing gown, with a large hat to cover flowing blonde hair. According to Deborah Solomon the work “takes its name from the pretty, apple-cheeked Victorian doll-a real doll with blond tresses and a straw hat…” (153). Here, Cornell not only idealizes place and time, but beauty as well. For he made many of his boxes for young girls and older women who he was attracted to from a far.

The girl in this box then takes on a kind of model, in the way that it dominates the ‘scene’ of the box. In a kind of reverse voyeurism, Cornell has set the gazing eyes of the doll coming out of the tiny branches, partly masking the face of the girl in the shadow of woods. This creates a sense of disconnection between viewer and object that is found most commonly among Constructivists of the early 20th century. Cornell’s personalized constructivism is, like his own surrealism, all his own.

Cornell transforms the doll into a symbol of female as object, not a female as sexual object, but rather a female as a prudish object. The idealized Victorian form ‘hidden’ behind the trees then has less to do with the Surrealists of the time, whose main obsession were the psychosexual tendencies in man, than with Cornell’s own celibacy. The tree branches in this context then represent barriers separating the desired from the desiring. The Victorian-era clothing further suggests a conservative aesthetic that is more highly valued in the majority of Cornell’s work, but this isn’t simplistic nostalgia, but rather a haunting construction of remnant semiotic codes left over from generations past. The doll is not a an object presented as is, as are many of his other ‘ready-mades’ from his oeuvre, it is a highly personalized image that is being shielded and in a way protected from the newer societal constructs of the present.

At the same time his works bear an unmistakable stamp of the early to mid 20th century and would rarely be taken for anything other than the work of this master artisan. I’m reminded of Joseph Campbell’s immortal words in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, “the crux of the curious difficulty lies in the fact that our conscious views of what life ought to be seldom correspond to what life really is” (121). This difficulty is man’s attempt to traverse through the various courses of life, all the while trying to do battle between reality and another kind of reality that arises from certain primal needs and desires that cannot be satiated by the first kind of reality. Cornell’s work resides in the latter category, but I hesitate to label it simple fantasy fulfillment, for what a dark and dreary fantasy that might be. Instead I see Untitled (Bebe Marie) as a struggle with passion, again not simply of the surrealist sexual tendencies; a passion for connection through the constricted ‘branches’ of life, that often obscure what the reality of a goal might actually be.

For this piece the viewer becomes tied to looking beyond the sticks covering the doll, instead trying to make out the total shape of the doll as if the brush didn’t impede the view. This is what most of man’s journey consists of, trying to get past the surface level codes, signs and visual/aural games that are so often heaved on top of us. Further autobiographical readings imply that Cornell was trying to get at the heart of women. In taking such a reading the work comes of as a bit creepy, yet there remains an undeniably endearing quality to the piece, for Cornell studied women his entire life, offering up many a work in tribute to famous starlets and long since deceased dancers. He wouldn’t come into romantic relationships until the last decade of his life (Solomon). The everlasting gaze of the doll then, represents a promise for romantic vindication, an elegiac letter from the heart to an unknown love.

The readings become further complicated by one’s own proclivities towards the heartbreaking of dour. I chose the path of Neo-Romanticism in my description of desire for future loves while someone else more schooled in Surrealism and the Dadaists might read it as a deconstruction of form as it relates to societal models. This provides ample evidence that this piece, and many of his other shadow boxes have attained a kind of sui generis position in the art world, admired by many, rarely for the same reasons, never quite fitting in to one camp or another.

Cornell’s Untitled (Bebe Marie) is a work that expresses personal obsessions through collective cultural images that turns the viewer in on himself and his society. It is one piece in a continued study of desire, anachronisms, artistic form and repetition. Where would Pop Art be without him?

I also saw Cassavetes Love Streams at the BAMrose a few days ago and was pleasantly surprised by its density and oneiric qualities. It possesses a magic that I think is only matched by A Woman Under the Influence. It doesn't seem as well composed as that film or his other masterwork Faces, but what distracting tendencies it holds in its messy composition, it more than makes up for in its moment by moment exploration of familial relationships and the hardships of love an passion. It always has amazed me how Cassavetes can be so affecting on our emotions without ever falling into sentimentalism. It's a shame it's not out on DVD.

Happy Thanksgiving all.