On Skye

22 September 1989

On this journey, I had three principal goals: first, of course, was to attend the otter colloquium in West Germany, second, to visit my otter Mecca, Camusfeàrna, and finally, to track and observe Lutra lutra in the wild. With the first two goals now on the scoreboard, I set out to achieve my hat trick today on the Isle of Skye.

I was doubly anxious to visit Skye now because when Mother and I went in 1974, our time there had been completely spoiled by foul weather. The rain and mist were so thick, we literally couldn't see a thing on what was supposed to be the most beautiful of all Scotland's islands. I doubt we had been on Skye for even a full hour before we retreated back to the mainland. Hopefully, the weather today would be more cooperative.

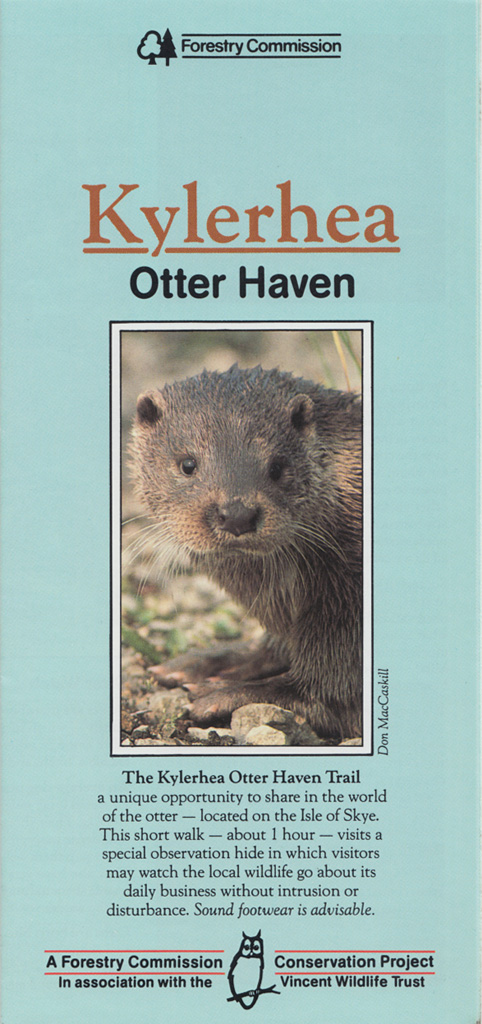

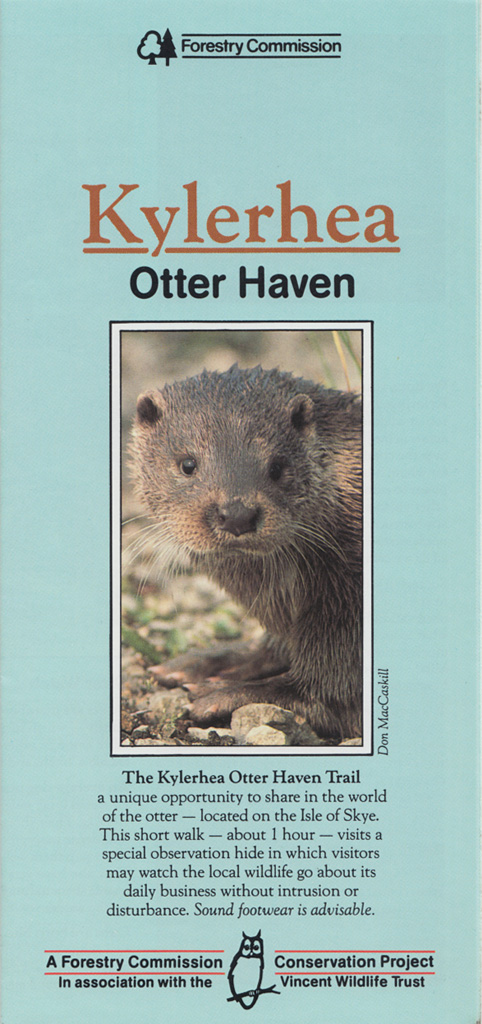

I was reasonably confident that this was going to be my lucky day in terms of spotting a wild otter. My pen-pal friend, Roger Parker, had told me about the nearby Kylerhea Otter Haven, where the Forestry Commission had a hide set up overlooking a section of coastline that was frequented by otters. Sounded like it was made to order for someone like me!

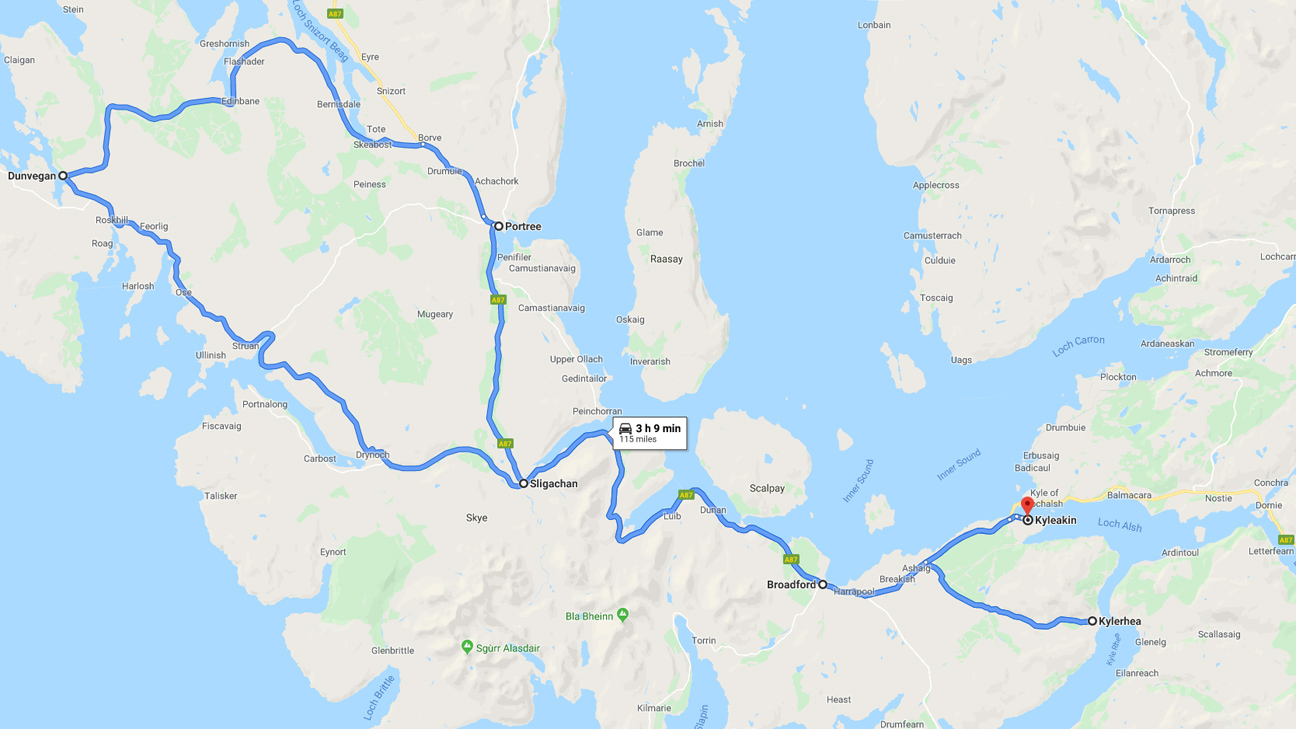

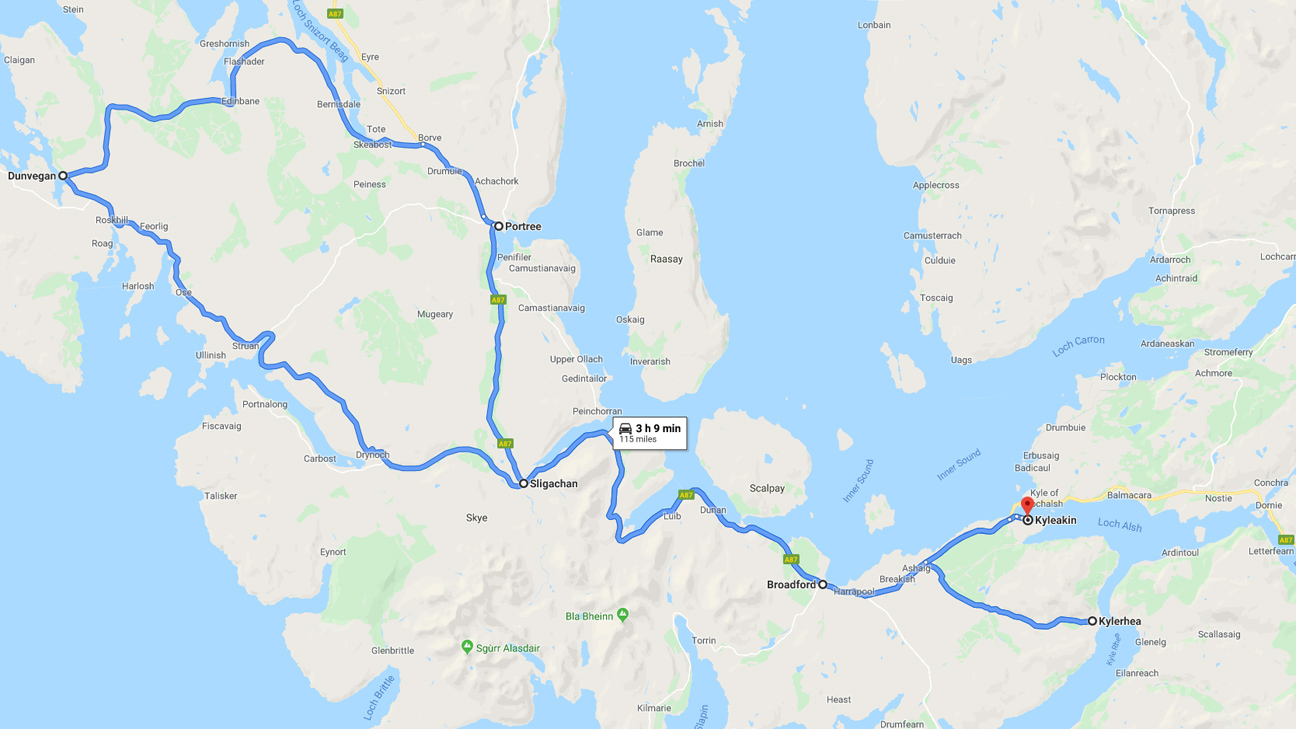

After leaving Sandaig on the afternoon of the 21st, I drove back over Mam Ratagan, then headed west on the A87 to Kyle of Lochalsh, where I took the car ferry to Kyleakin on Skye. Over supper at my B&B, I told my hostess of my intention to visit the Otter Haven the next morning. Her reply rather set me aback.

"Do you really think you'll see anything there? I've heard say it's a waste of time."

Well. Clearly, Mrs Branson had guests in the past who expressed dissatisfaction with their visit to the Otter Haven. I was undaunted, however. I knew there were otters living on the coast of Skye, and I was one of the most skilled otter-spotters alive. Mrs Branson's discouraging words notwithstanding, I had no reason to believe I wouldn't see the wee beasties at Kylerhea.

The sign is still there today, though the forestry pines are a bit taller. Photo by J Scott Shannon.

Most people work "9-to-5," but a wildlife biologist has to live on "critter time," i.e., your work hours must sync to those of the animals you're studying, whether or not they are convenient for you. Most of the world's otters are crepuscular, meaning they are mostly active at dawn and at dusk, so to give myself the best chance of seeing otters at Kylerhea, I had to get there well before sunrise. My notes indicate that I arrived at the hide at 0550... to find that the place was locked. Great.

The otter hide at Kylerhea, 22 September 1989. Photo by J Scott Shannon.

So when would it open? I had no idea. All I could do was just stand there getting rained on and eaten alive by midges until someone eventually came along and let me in. It was a long, miserable wait, I'll tell you. If I hadn't come so far, I would surely have left and tried again another day. However, given the circumstances, I really had no choice but to stick it out, and finally, after over 2 hours' wait, the trail steward finally came to my rescue at 0800.

Inside, the hide was spartan but well laid-out. A series of long narrow windows overlooked Kyle Rhea below. Wooden benches ran the length of the viewing area at different heights to accommodate adults and youngsters alike. Interpretive photos and text were on display to give visitor things to look at when there weren't any otters to watch. Which, unfortunately, turned out to be the vast majority of the time.

Fellow otter-spotters at Kylerhea Otter Haven, 22 September 1989. Photo by J Scott Shannon.

The first hour, I saw nothing mammalian except the heads of grey seals peering about in the shallows by the lighthouse. Several parties of visitors arrived in turn, binoculars and cameras at the ready. Most would quickly spot the seals, and, imagining they were seeing otters, exclaim "Oooh! Ahhh!," then leave feeling well pleased. I did not have the heart to tell them that they actually only saw seals and not otters at all. People made this mistake at Trinidad all the time, but I never said anything. If someone who saw a seal thought it was an otter, and was thrilled by their discovery, who was I to spoil the experience for them?

The periscoping pinnipeds were no consolation for me, however. As far as I was concerned, watching seals was just barely more exciting than watching logs float. And still, after two hours in the hide, I'd seen no sign of otters whatsoever. I was beginning to suspect that Mrs Branson had been right about this place, after all.

Even without otters, though, the view from the hide was grand, indeed. The place was beautifully situated in the middle of Kyle Rhea Sound.

The view to the north...

...and to the south. Sandaig is just out of view beyond the point. Photos by J Scott Shannon.

I killed some more time looking through the Otter Haven's guest book. The comments were largely positive; most being some variant of "Brilliant!" (I suspected those were the jubilant seal-spotters.) A few others were evidently penned by more disappointed visitors, with the most biting criticism being: "P.R. JOB. SPECIOUS." Yikes. Still, I was utterly determined to stay all day if necessary. I would NOT be discouraged.

And then, finally, at 1059, I saw movement directly down from the hide, and there it was! An otter! No doubt about it. Seals mostly just bob in place, but otters are always on the move, and this fellow was swimming quite purposefully north right along the shoreline.

He (I suspected it was a young male) hauled out on one of the tidal rocks as I scrambled for my camera. Can you see him there, at the white arrow; white head, brown body? The image is fuzzy, but that's the best picture I was able to get of my elusive quarry during the time he was in view.

Before the otter left the rock, he sprainted, then continued swimming north along the shore, fishing in the seaweed as he went. He then swam past the lighthouse and a rocky promontory before disappearing up the mouth of a burn. Altogether, I only got to watch the otter for 12 minutes, but I was thrilled beyond words. The long, boring wait had been totally worth it!

Mission again accomplished, I was now free to spend the rest of the day exploring Skye. But first, I was famished, and it would probably be a good idea if I ate something before I did anything else.

At Broadford, I stopped at what was then called the Strathcorry Restaurant for brunch. Near the entrance, they had the typical array of tourist brochures, and I looked them over for places to go and things to do on Skye. As I mentioned in a previous post, I was at the time a big fan of the film "Highlander," so when I saw Dunvegan Castle was the home of the Clan MacLeod, that seemed a natural for the day's travel destination. (Obviously, I knew the film had no basis in reality whatsoever, but I was still interested to learn about the actual Clan MacLeod!)

The drive into the interior and along the west coast of Skye was indeed spectacular. I was most impressed with the Red Cuillin east of Sligachan. They looked to me like the mountains of the moon. Most remarkable was the corbett "Glamaig": Skye's Fujiyama.

Glamaig, 22 September 1989. The view today has changed hardly at all, except for the road signs. Photo ©J Scott Shannon.

Photo by J Scott Shannon.

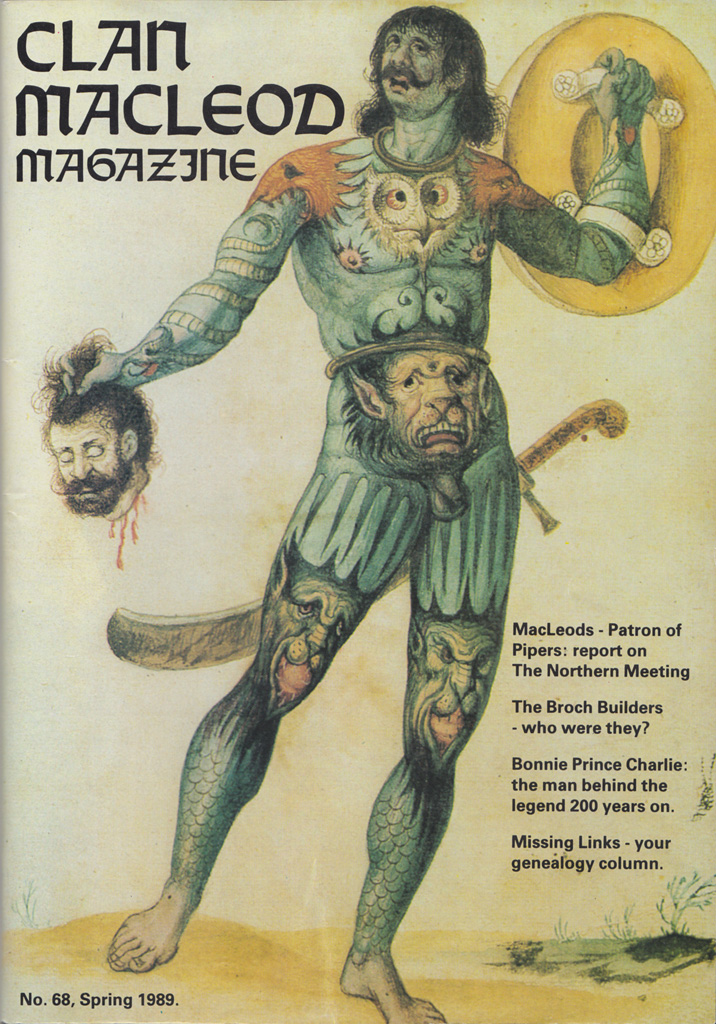

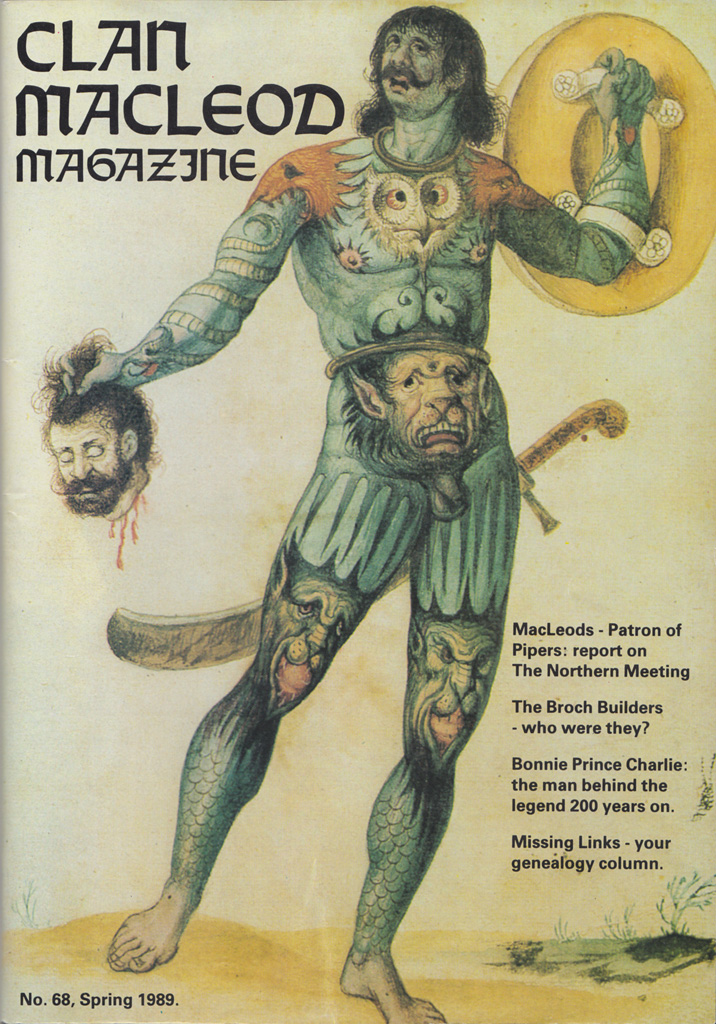

Dunvegan Castle had some interesting antiquities, however, my most memorable discovery there was the character gracing the then-current cover of the Clan magazine. This head-hunting Highlander was most decidedly not Christoper Lambert!

Pictish warrior by John White, c.1590, Trustees of the British Museum.

It was here in the car park at Dunvegan that I finally snapped a portrait of my magic carpet in Scotland: a 1989 Austin Maestro. A great-handling compact sedan!

After completing the Dunvegan loop through Portree, I stopped again at the Strathcorry Restaurant in Broadford, this time for tea. My waitress from brunch was still there, and she asked me how I enjoyed my day. It was brilliant, of course! As I prepared to depart, I once more perused their little brochure and book stand, found yet another paperback variant of Ring of Bright Water that I hadn't seen before, and bought it to celebrate my otter sighting from this morning past.

Back at Kyleakin, I finally got to spend some time quietly contemplating Eilean Bàn, Kyleakin Lighthouse, and Gavin Maxwell's brief period in residence there.

Eilean Bàn, Kyle Akin, Skye, 22 September 1989. The Skye Bridge now looms over the mid-19th-century lighthouse. Photo ©J Scott Shannon.

I had no inkling at the time that, only five years later, a modern highway would span that lonely isle. I know Skye Bridge must be a welcome convenience to the Isle's residents and visitors alike, but to me, it seems almost a desecration of a place that should properly have remained forever inviolate from the intrusion of civilization. (And I believe Maxwell, himself, would agree.)

Finally returning to my B&B, I gleefully told Mrs Branson that I did in fact see an otter at Kylerhea! Judging by her purse-lipped reaction, though, I doubt she really believed me. But, whatever, people like myself who came to Skye in search of otters were good patrons for her B&B, so in the end, I daresay Mrs Branson had no business complaining.

On this journey, I had three principal goals: first, of course, was to attend the otter colloquium in West Germany, second, to visit my otter Mecca, Camusfeàrna, and finally, to track and observe Lutra lutra in the wild. With the first two goals now on the scoreboard, I set out to achieve my hat trick today on the Isle of Skye.

I was doubly anxious to visit Skye now because when Mother and I went in 1974, our time there had been completely spoiled by foul weather. The rain and mist were so thick, we literally couldn't see a thing on what was supposed to be the most beautiful of all Scotland's islands. I doubt we had been on Skye for even a full hour before we retreated back to the mainland. Hopefully, the weather today would be more cooperative.

I was reasonably confident that this was going to be my lucky day in terms of spotting a wild otter. My pen-pal friend, Roger Parker, had told me about the nearby Kylerhea Otter Haven, where the Forestry Commission had a hide set up overlooking a section of coastline that was frequented by otters. Sounded like it was made to order for someone like me!

After leaving Sandaig on the afternoon of the 21st, I drove back over Mam Ratagan, then headed west on the A87 to Kyle of Lochalsh, where I took the car ferry to Kyleakin on Skye. Over supper at my B&B, I told my hostess of my intention to visit the Otter Haven the next morning. Her reply rather set me aback.

"Do you really think you'll see anything there? I've heard say it's a waste of time."

Well. Clearly, Mrs Branson had guests in the past who expressed dissatisfaction with their visit to the Otter Haven. I was undaunted, however. I knew there were otters living on the coast of Skye, and I was one of the most skilled otter-spotters alive. Mrs Branson's discouraging words notwithstanding, I had no reason to believe I wouldn't see the wee beasties at Kylerhea.

The sign is still there today, though the forestry pines are a bit taller. Photo by J Scott Shannon.

Most people work "9-to-5," but a wildlife biologist has to live on "critter time," i.e., your work hours must sync to those of the animals you're studying, whether or not they are convenient for you. Most of the world's otters are crepuscular, meaning they are mostly active at dawn and at dusk, so to give myself the best chance of seeing otters at Kylerhea, I had to get there well before sunrise. My notes indicate that I arrived at the hide at 0550... to find that the place was locked. Great.

The otter hide at Kylerhea, 22 September 1989. Photo by J Scott Shannon.

So when would it open? I had no idea. All I could do was just stand there getting rained on and eaten alive by midges until someone eventually came along and let me in. It was a long, miserable wait, I'll tell you. If I hadn't come so far, I would surely have left and tried again another day. However, given the circumstances, I really had no choice but to stick it out, and finally, after over 2 hours' wait, the trail steward finally came to my rescue at 0800.

Inside, the hide was spartan but well laid-out. A series of long narrow windows overlooked Kyle Rhea below. Wooden benches ran the length of the viewing area at different heights to accommodate adults and youngsters alike. Interpretive photos and text were on display to give visitor things to look at when there weren't any otters to watch. Which, unfortunately, turned out to be the vast majority of the time.

Fellow otter-spotters at Kylerhea Otter Haven, 22 September 1989. Photo by J Scott Shannon.

The first hour, I saw nothing mammalian except the heads of grey seals peering about in the shallows by the lighthouse. Several parties of visitors arrived in turn, binoculars and cameras at the ready. Most would quickly spot the seals, and, imagining they were seeing otters, exclaim "Oooh! Ahhh!," then leave feeling well pleased. I did not have the heart to tell them that they actually only saw seals and not otters at all. People made this mistake at Trinidad all the time, but I never said anything. If someone who saw a seal thought it was an otter, and was thrilled by their discovery, who was I to spoil the experience for them?

The periscoping pinnipeds were no consolation for me, however. As far as I was concerned, watching seals was just barely more exciting than watching logs float. And still, after two hours in the hide, I'd seen no sign of otters whatsoever. I was beginning to suspect that Mrs Branson had been right about this place, after all.

Even without otters, though, the view from the hide was grand, indeed. The place was beautifully situated in the middle of Kyle Rhea Sound.

The view to the north...

...and to the south. Sandaig is just out of view beyond the point. Photos by J Scott Shannon.

I killed some more time looking through the Otter Haven's guest book. The comments were largely positive; most being some variant of "Brilliant!" (I suspected those were the jubilant seal-spotters.) A few others were evidently penned by more disappointed visitors, with the most biting criticism being: "P.R. JOB. SPECIOUS." Yikes. Still, I was utterly determined to stay all day if necessary. I would NOT be discouraged.

And then, finally, at 1059, I saw movement directly down from the hide, and there it was! An otter! No doubt about it. Seals mostly just bob in place, but otters are always on the move, and this fellow was swimming quite purposefully north right along the shoreline.

He (I suspected it was a young male) hauled out on one of the tidal rocks as I scrambled for my camera. Can you see him there, at the white arrow; white head, brown body? The image is fuzzy, but that's the best picture I was able to get of my elusive quarry during the time he was in view.

Before the otter left the rock, he sprainted, then continued swimming north along the shore, fishing in the seaweed as he went. He then swam past the lighthouse and a rocky promontory before disappearing up the mouth of a burn. Altogether, I only got to watch the otter for 12 minutes, but I was thrilled beyond words. The long, boring wait had been totally worth it!

Mission again accomplished, I was now free to spend the rest of the day exploring Skye. But first, I was famished, and it would probably be a good idea if I ate something before I did anything else.

At Broadford, I stopped at what was then called the Strathcorry Restaurant for brunch. Near the entrance, they had the typical array of tourist brochures, and I looked them over for places to go and things to do on Skye. As I mentioned in a previous post, I was at the time a big fan of the film "Highlander," so when I saw Dunvegan Castle was the home of the Clan MacLeod, that seemed a natural for the day's travel destination. (Obviously, I knew the film had no basis in reality whatsoever, but I was still interested to learn about the actual Clan MacLeod!)

The drive into the interior and along the west coast of Skye was indeed spectacular. I was most impressed with the Red Cuillin east of Sligachan. They looked to me like the mountains of the moon. Most remarkable was the corbett "Glamaig": Skye's Fujiyama.

Glamaig, 22 September 1989. The view today has changed hardly at all, except for the road signs. Photo ©J Scott Shannon.

Photo by J Scott Shannon.

Dunvegan Castle had some interesting antiquities, however, my most memorable discovery there was the character gracing the then-current cover of the Clan magazine. This head-hunting Highlander was most decidedly not Christoper Lambert!

Pictish warrior by John White, c.1590, Trustees of the British Museum.

It was here in the car park at Dunvegan that I finally snapped a portrait of my magic carpet in Scotland: a 1989 Austin Maestro. A great-handling compact sedan!

After completing the Dunvegan loop through Portree, I stopped again at the Strathcorry Restaurant in Broadford, this time for tea. My waitress from brunch was still there, and she asked me how I enjoyed my day. It was brilliant, of course! As I prepared to depart, I once more perused their little brochure and book stand, found yet another paperback variant of Ring of Bright Water that I hadn't seen before, and bought it to celebrate my otter sighting from this morning past.

Back at Kyleakin, I finally got to spend some time quietly contemplating Eilean Bàn, Kyleakin Lighthouse, and Gavin Maxwell's brief period in residence there.

Eilean Bàn, Kyle Akin, Skye, 22 September 1989. The Skye Bridge now looms over the mid-19th-century lighthouse. Photo ©J Scott Shannon.

I had no inkling at the time that, only five years later, a modern highway would span that lonely isle. I know Skye Bridge must be a welcome convenience to the Isle's residents and visitors alike, but to me, it seems almost a desecration of a place that should properly have remained forever inviolate from the intrusion of civilization. (And I believe Maxwell, himself, would agree.)

Finally returning to my B&B, I gleefully told Mrs Branson that I did in fact see an otter at Kylerhea! Judging by her purse-lipped reaction, though, I doubt she really believed me. But, whatever, people like myself who came to Skye in search of otters were good patrons for her B&B, so in the end, I daresay Mrs Branson had no business complaining.