At the Natural History Museum

12-13 September 1989

Today was to be my much-anticipated visit to the British Museum (Natural History), as the institution was then still named.

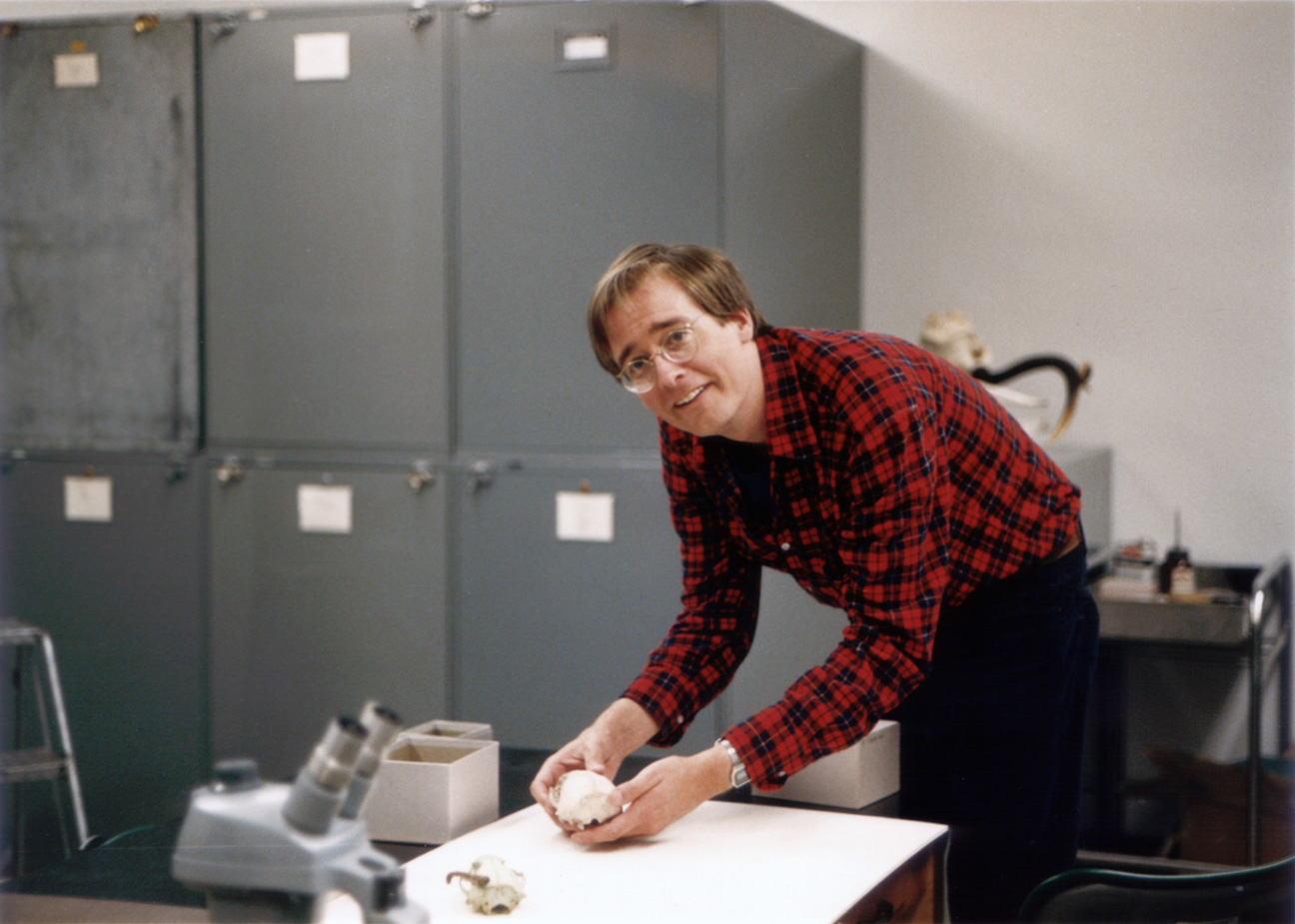

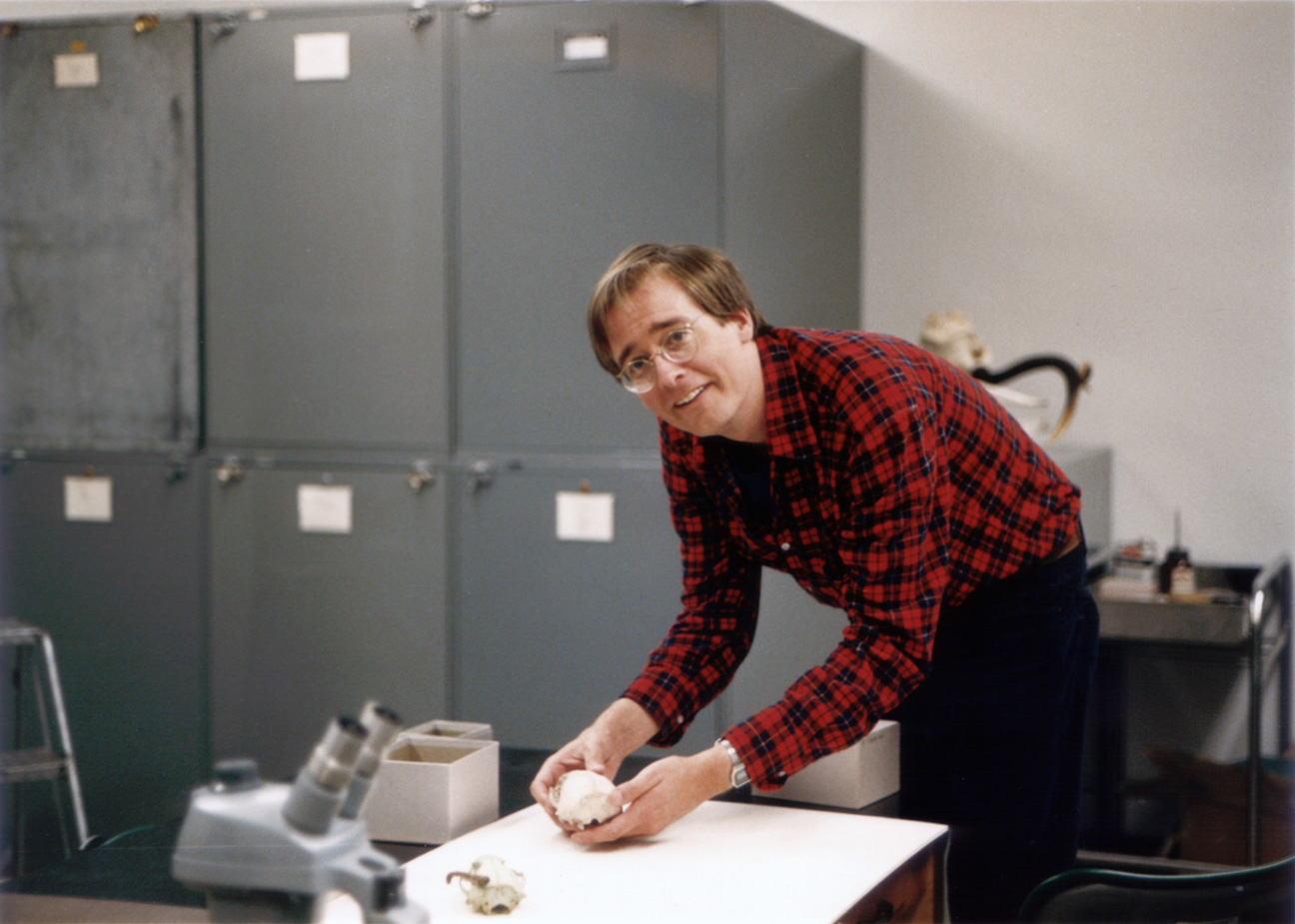

Although I was studying otter behavior for my thesis project, I was never simply a behaviorist. I loved the entire field of biology, and was particularly interested in the taxonomy and evolutionary history of the vertebrates. Additionally, one of my practical specialties was museum curation: preparing biological specimens for study and preservation in collections. In 1987, I was hired as curator of the Fisheries Museum in the Wildlife Department at Humboldt State University, and was concurrently associated with the corresponding facility in the Biology Department, as well. I found it to be very fulfilling work, and I fancied I might even continue with it as a career after I got my Ph.D.

Yours Truly inspecting otter crania in the Vertebrate Museum at HSU, September, 1987.

So in 1989, when I decided to attend the Otter Colloquium in West Germany, I of course made arrangements to visit the revered and august facility on Cromwell Road in London which was home to one of the foremost natural history collections in the world. I was especially anxious to view their otter material, which I already knew included many specimens of significance.

The British Museum (Natural History), 12 September 1989. Photos by J Scott Shannon.

I'd written a letter of introduction in advance of my visit, and requested permission to view their collection. In accordance with a tradition of reciprocity, I brought along with me several obscure manuscripts about the evolution of otters in general and North American genera in particular which I was reasonably certain would be new to them and which they might like to add to their research library.

My actual appointment on 12 September wasn't until after lunch, however, so upon arriving on the premises at 1040, I passed the time perambulating around the public spaces of the museum.

The central hall of Britain's Cathedral of Nature. Photo by J Scott Shannon.

One of the more interesting non-otter-related exhibits was their marsupial display, which included an example of the Tasmanian Wolf, which was believed to have become extinct only as recently as 1936.

†Thylacinus cynocephalus. Photo by J Scott Shannon.

According to my diary, I also viewed a diorama on the evolution of the domestic dog which was an unexpected pleasure, and of course, ogled their impressive collection of articulated dinosaur skeletons.

But then it was on to my intended destination: the otter specimens! The staff in the Department of Zoology were very welcoming and friendly, and surprisingly informal. They were quite pleased to receive the manuscripts I'd brought along, and I was correct in my assumption that they had not seen those specific works before.

I was then escorted up to the 9th floor of the vertebrate stacks, where the otter material was pointed out to me. Then, unexpectedly, I was left entirely alone to view everything completely at my leisure.

Among the many amazing specimens I found there, these most stood out:

• A sea otter pelt collected by Archibald Menzies in 1793 during the Vancouver Expedition.

• The type specimen of the giant otter of South America, Pteronura brasiliensis, curated and cataloged by J. E. Gray in 1837.

• A skull of the South American marine otter, Lontra felina, collected in 1834 by none other than a young Charles Darwin during his voyage on the H.M.S. Beagle.

But, to me, the greatest treasure of all that I held in my own hands that day was...

• The type specimen of Lutrogale perspicillata maxwelli.

As told in Chapter 8 of his book "A Reed Shaken by the Wind," and again in his classic "Ring of Bright Water," author and adventurer Gavin Maxwell bought this peltry from a Marsh Arab sheikh in Southern Iraq in Spring, 1957, and brought it - and his newly-acquired pet of the same species - back to the U.K., where taxonomists at the London Zoological Society determined the skin and the living example to be a new, previously unknown subspecies of the Asian smooth-coated otter.

It was like a holy relic to me. This was the original, seminal object collected by Maxwell himself. Absolutely incredible. I passed my hand over its thick, exquisitely soft fur in wonder. The moment and the thing itself were pure magic to me. My trip diary says that I made a copy of the tag on the L. p. maxwelli pelt, but if I did (and I don't actually remember that I did), it must be lost somewhere in my voluminous collection of otter ephemera. Such a shame. I would dearly love to see that once again.

The next morning, I returned to view their collection of otter fossils. This time, I definitely needed help to navigate through the many cabinets of specimens, and I was assisted by a fellow named Alan Gentry.

In one drawer dedicated to Neogene lutrines, there was one specimen - actually a cast, not an actual fossil, of a portion of a lower jaw of an individual of the extinct genus †Enhydriodon, a bunodont otter from the Pliocene of India - of which there was a duplicate. I pointed out that there were two, made puppy eyes to Alan, and, thanks to the aforementioned practice of reciprocity, he let me have the duplicate cast. Such an honor! I was absolutely tickled, and expressed profuse thanks. The Pliocene was the 'golden age' of otters in the fossil record, so to have even a replica of part of a lutrine from that period was highly significant to me. (Those are my notations on the label, BTW. All relevant info neatly inscribed in India ink on archive card stock with an engineering pen, just like a good curator would.)

My treasured souvenir from the Palaeontology Section of the British Museum (Natural History). Thanks again, Alan!

I left the Natural History Museum feeling supremely satisfied. What an amazing place. I very much envied my new friends who worked there. I wished I didn't have to go. I could easily have spent a week on that 9th floor alone, I'll tell you, but I felt the two days I did have to explore it was privilege enough. I dearly hoped I could return someday; perhaps even to be employed there, who knows? Indeed, anything seemed possible to me back in those miracle days.

Today was to be my much-anticipated visit to the British Museum (Natural History), as the institution was then still named.

Although I was studying otter behavior for my thesis project, I was never simply a behaviorist. I loved the entire field of biology, and was particularly interested in the taxonomy and evolutionary history of the vertebrates. Additionally, one of my practical specialties was museum curation: preparing biological specimens for study and preservation in collections. In 1987, I was hired as curator of the Fisheries Museum in the Wildlife Department at Humboldt State University, and was concurrently associated with the corresponding facility in the Biology Department, as well. I found it to be very fulfilling work, and I fancied I might even continue with it as a career after I got my Ph.D.

Yours Truly inspecting otter crania in the Vertebrate Museum at HSU, September, 1987.

So in 1989, when I decided to attend the Otter Colloquium in West Germany, I of course made arrangements to visit the revered and august facility on Cromwell Road in London which was home to one of the foremost natural history collections in the world. I was especially anxious to view their otter material, which I already knew included many specimens of significance.

The British Museum (Natural History), 12 September 1989. Photos by J Scott Shannon.

I'd written a letter of introduction in advance of my visit, and requested permission to view their collection. In accordance with a tradition of reciprocity, I brought along with me several obscure manuscripts about the evolution of otters in general and North American genera in particular which I was reasonably certain would be new to them and which they might like to add to their research library.

My actual appointment on 12 September wasn't until after lunch, however, so upon arriving on the premises at 1040, I passed the time perambulating around the public spaces of the museum.

The central hall of Britain's Cathedral of Nature. Photo by J Scott Shannon.

One of the more interesting non-otter-related exhibits was their marsupial display, which included an example of the Tasmanian Wolf, which was believed to have become extinct only as recently as 1936.

†Thylacinus cynocephalus. Photo by J Scott Shannon.

According to my diary, I also viewed a diorama on the evolution of the domestic dog which was an unexpected pleasure, and of course, ogled their impressive collection of articulated dinosaur skeletons.

But then it was on to my intended destination: the otter specimens! The staff in the Department of Zoology were very welcoming and friendly, and surprisingly informal. They were quite pleased to receive the manuscripts I'd brought along, and I was correct in my assumption that they had not seen those specific works before.

I was then escorted up to the 9th floor of the vertebrate stacks, where the otter material was pointed out to me. Then, unexpectedly, I was left entirely alone to view everything completely at my leisure.

Among the many amazing specimens I found there, these most stood out:

• A sea otter pelt collected by Archibald Menzies in 1793 during the Vancouver Expedition.

• The type specimen of the giant otter of South America, Pteronura brasiliensis, curated and cataloged by J. E. Gray in 1837.

• A skull of the South American marine otter, Lontra felina, collected in 1834 by none other than a young Charles Darwin during his voyage on the H.M.S. Beagle.

But, to me, the greatest treasure of all that I held in my own hands that day was...

• The type specimen of Lutrogale perspicillata maxwelli.

As told in Chapter 8 of his book "A Reed Shaken by the Wind," and again in his classic "Ring of Bright Water," author and adventurer Gavin Maxwell bought this peltry from a Marsh Arab sheikh in Southern Iraq in Spring, 1957, and brought it - and his newly-acquired pet of the same species - back to the U.K., where taxonomists at the London Zoological Society determined the skin and the living example to be a new, previously unknown subspecies of the Asian smooth-coated otter.

It was like a holy relic to me. This was the original, seminal object collected by Maxwell himself. Absolutely incredible. I passed my hand over its thick, exquisitely soft fur in wonder. The moment and the thing itself were pure magic to me. My trip diary says that I made a copy of the tag on the L. p. maxwelli pelt, but if I did (and I don't actually remember that I did), it must be lost somewhere in my voluminous collection of otter ephemera. Such a shame. I would dearly love to see that once again.

The next morning, I returned to view their collection of otter fossils. This time, I definitely needed help to navigate through the many cabinets of specimens, and I was assisted by a fellow named Alan Gentry.

In one drawer dedicated to Neogene lutrines, there was one specimen - actually a cast, not an actual fossil, of a portion of a lower jaw of an individual of the extinct genus †Enhydriodon, a bunodont otter from the Pliocene of India - of which there was a duplicate. I pointed out that there were two, made puppy eyes to Alan, and, thanks to the aforementioned practice of reciprocity, he let me have the duplicate cast. Such an honor! I was absolutely tickled, and expressed profuse thanks. The Pliocene was the 'golden age' of otters in the fossil record, so to have even a replica of part of a lutrine from that period was highly significant to me. (Those are my notations on the label, BTW. All relevant info neatly inscribed in India ink on archive card stock with an engineering pen, just like a good curator would.)

My treasured souvenir from the Palaeontology Section of the British Museum (Natural History). Thanks again, Alan!

I left the Natural History Museum feeling supremely satisfied. What an amazing place. I very much envied my new friends who worked there. I wished I didn't have to go. I could easily have spent a week on that 9th floor alone, I'll tell you, but I felt the two days I did have to explore it was privilege enough. I dearly hoped I could return someday; perhaps even to be employed there, who knows? Indeed, anything seemed possible to me back in those miracle days.