The Otter Trust

10 September 1989

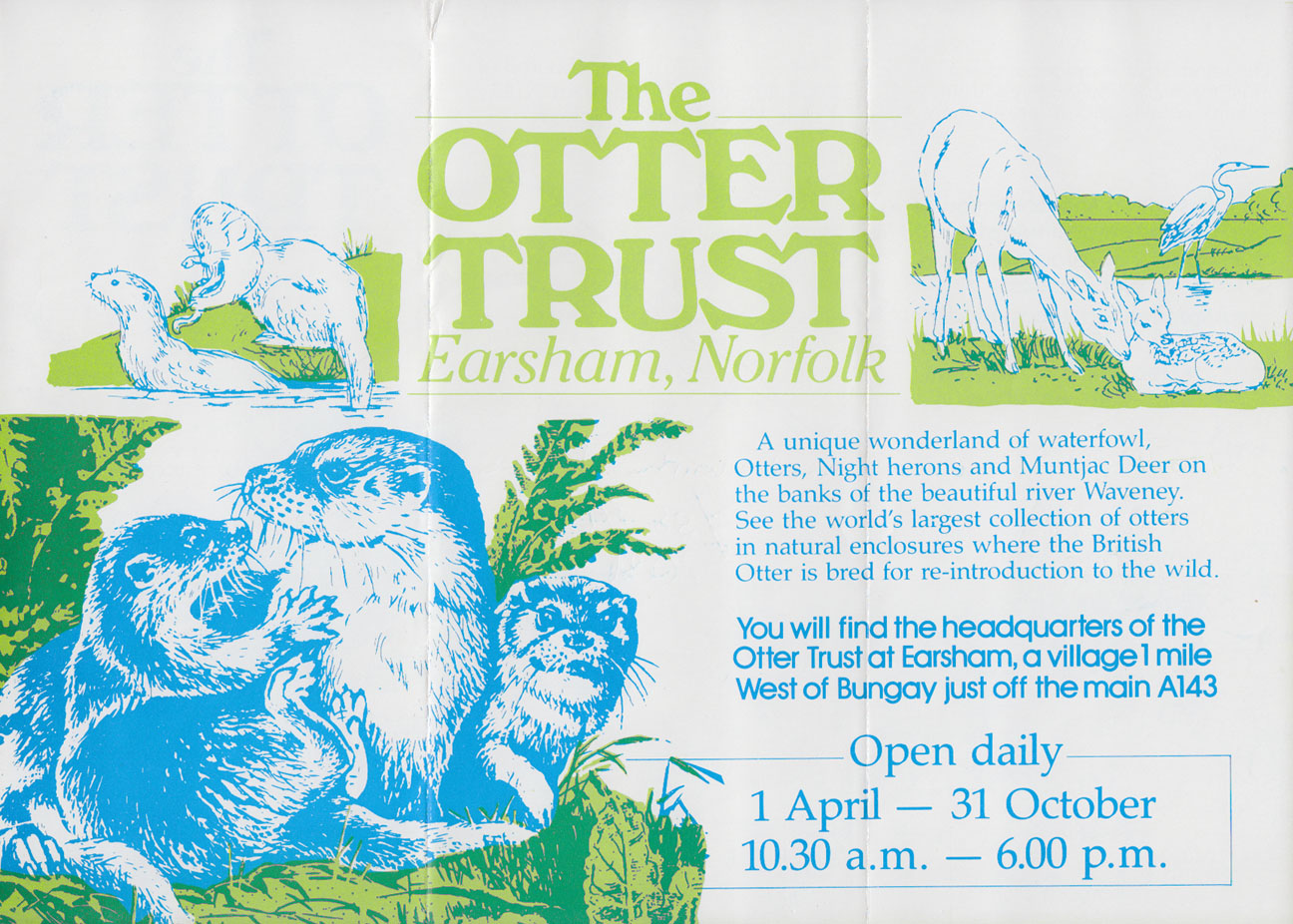

Next stop on my itinerary was The Otter Trust: a conservation park in Earsham near Bungay in Suffolk.

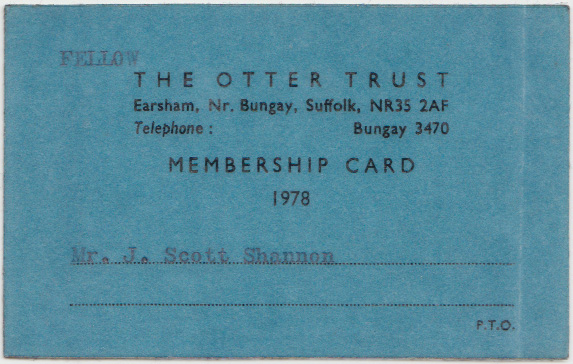

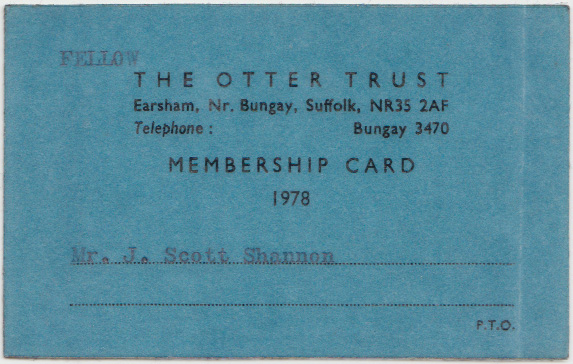

I was really looking forward to this. I'd been informally affiliated with The Otter Trust for 11 years already; first as a dues-paying member, then as a delegated representative at previous otter meetings. So, naturally, when I traveled to Europe for this just-concluded colloquium, I wanted to finally visit the place and meet the man who had so inspired me in those earlier years.

I was particularly anxious to become better acquainted with the Trust's founder: Philip Wayre. He was one of my 'otter heroes'- one of the very few who had taken up the cause of the animals' preservation, long before most were even aware that they were in trouble worldwide. I very much wanted to follow in Mr. Wayre's footsteps, and I did to some degree, starting my own conservation group for North American otters in 1980.

I had only recently come to understand, however, that Mr. Wayre was something of a controversial figure. In all innocence, I'd told several people at the recent meeting that I intended to visit the Otter Trust. Each time I did, though, I received uniformly negative reactions. Many expressed overt disapproval of Mr. Wayre and his work, with one woman even exclaiming, "That man!" Oh, dear. I had no idea. It seemed no one at the colloquium had a favorable opinion of Philip Wayre.

The main complaint against Wayre seemed to be that he had released otters from other parts of Eurasia into British habitats. As a biologist, I understood this objection. While it is always desirable to translocate local genetic stock if possible, the fact was that British otters were so close to extinction that there really wasn't a surplus population anywhere in the Isles that could stand being trapped and relocated in any significant numbers. In a case like that, you almost had no choice but to go with whatever was available. So I rather sympathized with Mr. Wayre's way of doing things. I knew that, in America, often otters from Louisiana were relocated to places like North Dakota, where they were very much a non-native subspecies. Notwithstanding what was ideal from a genetic point of view, you did what you needed to do to get the animals back. And maybe, it occurred to me, if the British otters' gene pool was so inbred, as it likely was, maybe it could benefit from a little outbreeding with more genetically robust populations elsewhere.

But whatever, I wasn't going to judge someone without meeting them. I'd written Mr. Wayre in advance, of course, giving the date for my visit. I knew the Wayres lived on the premises, too, so I didn't anticipate any problem in that regard.

I took British Rail from my ferry embarkation point of Harwich to Stowmarket, thence to Diss, the nearest station to the Otter Trust at Earsham.

I arrived by taxi at 1045, not long after the park's opening, and introduced myself as an expected guest of Mr. Wayre and his wife. There was a kindly lady there named Audrey who was very solicitous and attentive to me. Word was sent to the Wayres that I'd arrived. However, as lunchtime came and went, I began to harbor doubts that the hoped-for meeting would take place.

Photos by J Scott Shannon.

In the meantime, I walked around the park. In general layout, it was very similar to the Otter-Zentrum: otters in naturalistic enclosures, singly, and in groups. One big difference I quickly noted, though, was that many of the otters were displaying repetitive behaviors typical of zoo animals that had become neuroticized due to a lack of environmental enrichment. I didn't see any of that at the Otter Centre. To a layman, this stereotyped behavior looks 'cute' and 'playful', but to my trained eye, it was a rather distressing sign. It indicated to me that these otters had been kept in captivity for too long. I doubted any of them were releasable, frankly. Behaviorally-stunted animals such as this wouldn't last long at all out in the wild. I came away from the pens at the Otter Trust having a distinctly different opinion about the place than its counterpart in Germany.

Anyway, after four long hours passed, I finally got the word that the Wayres had regretfully declined to see me. No specific reason was given. No begging my pardon due to illness, or because it was lunchtime, or naptime, or that they had other engagements. None of those things. They had simply turned me away. I was dismissed.

How discourteous. I'd corresponded with this man for over 10 years, even been his personal representative, and yet he refused to even come shake my hand and say how do you do? I was incredulous, and very disappointed. I left thinking that my colleagues' opinions were apparently justified. Philip Wayre was, indeed, a less-than-agreeable man.

When I returned home, there was a letter waiting for me from The Otter Trust. I anticipated it would contain at least an explanation for what happened when I visited, and perhaps an apology, but instead, it was a screed from Mr. Wayre decrying the fact that a statement he'd wanted to be read to the attendees at the V.IOC about his efforts in England hadn't been read at all, and enclosed herewith was said statement for my attention. Needless to say, I didn't reply, nor did I ever contact him again.

Philip Wayre lived another 25 years and died in 2014 at the age of 93. The charity he founded still exists, but the sanctuary that I visited at Earsham is no more. It's now the home of another conservation trust.

The Otter Trust's Facebook page contains no current photos of otters, so I'm supposing they no longer have any. For all intents and purposes, it appears Mr. Wayre's work did not survive him. Such a shame. Perhaps if he had possessed a more congenial and cooperative nature, this fate could have been avoided. An object lesson for those who imagine they are a world unto themselves.

Next stop on my itinerary was The Otter Trust: a conservation park in Earsham near Bungay in Suffolk.

I was really looking forward to this. I'd been informally affiliated with The Otter Trust for 11 years already; first as a dues-paying member, then as a delegated representative at previous otter meetings. So, naturally, when I traveled to Europe for this just-concluded colloquium, I wanted to finally visit the place and meet the man who had so inspired me in those earlier years.

I was particularly anxious to become better acquainted with the Trust's founder: Philip Wayre. He was one of my 'otter heroes'- one of the very few who had taken up the cause of the animals' preservation, long before most were even aware that they were in trouble worldwide. I very much wanted to follow in Mr. Wayre's footsteps, and I did to some degree, starting my own conservation group for North American otters in 1980.

I had only recently come to understand, however, that Mr. Wayre was something of a controversial figure. In all innocence, I'd told several people at the recent meeting that I intended to visit the Otter Trust. Each time I did, though, I received uniformly negative reactions. Many expressed overt disapproval of Mr. Wayre and his work, with one woman even exclaiming, "That man!" Oh, dear. I had no idea. It seemed no one at the colloquium had a favorable opinion of Philip Wayre.

The main complaint against Wayre seemed to be that he had released otters from other parts of Eurasia into British habitats. As a biologist, I understood this objection. While it is always desirable to translocate local genetic stock if possible, the fact was that British otters were so close to extinction that there really wasn't a surplus population anywhere in the Isles that could stand being trapped and relocated in any significant numbers. In a case like that, you almost had no choice but to go with whatever was available. So I rather sympathized with Mr. Wayre's way of doing things. I knew that, in America, often otters from Louisiana were relocated to places like North Dakota, where they were very much a non-native subspecies. Notwithstanding what was ideal from a genetic point of view, you did what you needed to do to get the animals back. And maybe, it occurred to me, if the British otters' gene pool was so inbred, as it likely was, maybe it could benefit from a little outbreeding with more genetically robust populations elsewhere.

But whatever, I wasn't going to judge someone without meeting them. I'd written Mr. Wayre in advance, of course, giving the date for my visit. I knew the Wayres lived on the premises, too, so I didn't anticipate any problem in that regard.

I took British Rail from my ferry embarkation point of Harwich to Stowmarket, thence to Diss, the nearest station to the Otter Trust at Earsham.

I arrived by taxi at 1045, not long after the park's opening, and introduced myself as an expected guest of Mr. Wayre and his wife. There was a kindly lady there named Audrey who was very solicitous and attentive to me. Word was sent to the Wayres that I'd arrived. However, as lunchtime came and went, I began to harbor doubts that the hoped-for meeting would take place.

Photos by J Scott Shannon.

In the meantime, I walked around the park. In general layout, it was very similar to the Otter-Zentrum: otters in naturalistic enclosures, singly, and in groups. One big difference I quickly noted, though, was that many of the otters were displaying repetitive behaviors typical of zoo animals that had become neuroticized due to a lack of environmental enrichment. I didn't see any of that at the Otter Centre. To a layman, this stereotyped behavior looks 'cute' and 'playful', but to my trained eye, it was a rather distressing sign. It indicated to me that these otters had been kept in captivity for too long. I doubted any of them were releasable, frankly. Behaviorally-stunted animals such as this wouldn't last long at all out in the wild. I came away from the pens at the Otter Trust having a distinctly different opinion about the place than its counterpart in Germany.

Anyway, after four long hours passed, I finally got the word that the Wayres had regretfully declined to see me. No specific reason was given. No begging my pardon due to illness, or because it was lunchtime, or naptime, or that they had other engagements. None of those things. They had simply turned me away. I was dismissed.

How discourteous. I'd corresponded with this man for over 10 years, even been his personal representative, and yet he refused to even come shake my hand and say how do you do? I was incredulous, and very disappointed. I left thinking that my colleagues' opinions were apparently justified. Philip Wayre was, indeed, a less-than-agreeable man.

When I returned home, there was a letter waiting for me from The Otter Trust. I anticipated it would contain at least an explanation for what happened when I visited, and perhaps an apology, but instead, it was a screed from Mr. Wayre decrying the fact that a statement he'd wanted to be read to the attendees at the V.IOC about his efforts in England hadn't been read at all, and enclosed herewith was said statement for my attention. Needless to say, I didn't reply, nor did I ever contact him again.

Philip Wayre lived another 25 years and died in 2014 at the age of 93. The charity he founded still exists, but the sanctuary that I visited at Earsham is no more. It's now the home of another conservation trust.

The Otter Trust's Facebook page contains no current photos of otters, so I'm supposing they no longer have any. For all intents and purposes, it appears Mr. Wayre's work did not survive him. Such a shame. Perhaps if he had possessed a more congenial and cooperative nature, this fate could have been avoided. An object lesson for those who imagine they are a world unto themselves.