leave out the insurrection wholly

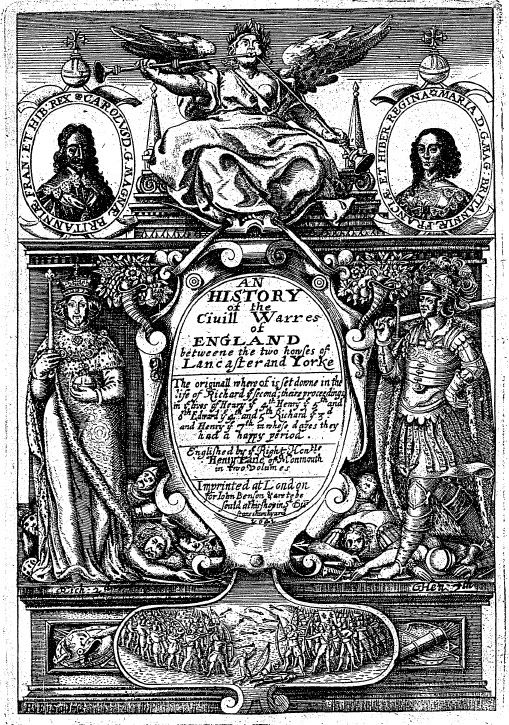

In my continuing if irregular series of interesting frontispieces to texts on the Wars of the Roses, I present to you one that I found in an old article called "Richard II and the Wars of the Roses," by Margaret Aston (it's in that collection of essays on Richard's reign dedicated to May McKisack), which is one of those wonderful articles that backs you up in terms of making an argument you agree with, but contains enough missing of the point in the particulars as to leave you a lot of room to disagree.

Aston's point is basically that depictions of Richard and his reign are always unduly influenced by the Tudor version of things which makes the deposition an originary moment that has to be slotted into a particular narrative paradigm, nothing new there certainly, although she doesn't say much about how a lot of the stuff the Tudor histories use in their selective readings is inherited from the Lancastrian chroniclers and especially Thomas of Walsingham, but maybe I missed some footnotes (I read the essay while walking from class to choir practice). Anyway, the thing I wanted to mention here is that she reproduces a fantastic illustration from a text that's too late for me to do much with in my diss but which I absolutely need to get back to at some point and, at least, refer to (along with George Daniel's 1649 Trinarchodia) in my conclusion.

Slightly higher-resolution but blurrier version

On your left, in disconcertingly clingy garments, is Richard II; on your right, in rather out-of-period armor, is Henry VII; in the middle, behind the title of course, is a pile of corpses. This may be the most concise expression of the Tudor narrative ever achieved.

You may notice, if the text isn't too blurry, that the subtitle proclaims that under Henry VII, the Wars of the Roses "had a happy period." Which is deeply, deeply disturbing. THE WARS OF THE ROSES ARE NOT A KOTEX AD THANK YOU VERY MUCH.

Biondi's history itself, from what I have read of it, is delightfully cracked-out, what with the bits of dialogue lifted straight from Shakespeare (I am guessing this is almost certainly the translator's doing), the long disquisition on Why None of the Theories About How Richard II Died Make Sense, and the occasionally cavalier disregard for the relation of events in chronological order. And the end of the chapter on Richard II's reign (which is, throughout, fairly weird anyway) is particularly brain-bending: having started the chapter (after the usual "Edward III, my lords, had seven sons" business) with a remark to the effect that Richard did a lot of neat and legitimately badass things that we're not going to talk about because they don't fit the narrative plan of the work, Biondi concludes it by saying that Richard was "a prince in many respects worthy to have reigned, if he had not reigned," a statement whose logic is wonderfully twisty -- Richard would have been a pretty good king if he hadn't been king, BUT being king made him unworthy to be king. It is fun stuff. I love having shiny new history texts to play with

Also, while we are on the subject of Richard II -- which may, in fact, be the single most redundant statement ever made on this blog -- perhaps you might be interested in perusing his extensive collection of shiny objects. This page was linked on Chaucer's blog recently and it is much with the coolness. Whatever disparities there are in the accounts of Richard II's life and reign, it is clear from every single piece of existing evidence that he was a man who loved his shiny objects.

Aston's point is basically that depictions of Richard and his reign are always unduly influenced by the Tudor version of things which makes the deposition an originary moment that has to be slotted into a particular narrative paradigm, nothing new there certainly, although she doesn't say much about how a lot of the stuff the Tudor histories use in their selective readings is inherited from the Lancastrian chroniclers and especially Thomas of Walsingham, but maybe I missed some footnotes (I read the essay while walking from class to choir practice). Anyway, the thing I wanted to mention here is that she reproduces a fantastic illustration from a text that's too late for me to do much with in my diss but which I absolutely need to get back to at some point and, at least, refer to (along with George Daniel's 1649 Trinarchodia) in my conclusion.

Slightly higher-resolution but blurrier version

On your left, in disconcertingly clingy garments, is Richard II; on your right, in rather out-of-period armor, is Henry VII; in the middle, behind the title of course, is a pile of corpses. This may be the most concise expression of the Tudor narrative ever achieved.

You may notice, if the text isn't too blurry, that the subtitle proclaims that under Henry VII, the Wars of the Roses "had a happy period." Which is deeply, deeply disturbing. THE WARS OF THE ROSES ARE NOT A KOTEX AD THANK YOU VERY MUCH.

Biondi's history itself, from what I have read of it, is delightfully cracked-out, what with the bits of dialogue lifted straight from Shakespeare (I am guessing this is almost certainly the translator's doing), the long disquisition on Why None of the Theories About How Richard II Died Make Sense, and the occasionally cavalier disregard for the relation of events in chronological order. And the end of the chapter on Richard II's reign (which is, throughout, fairly weird anyway) is particularly brain-bending: having started the chapter (after the usual "Edward III, my lords, had seven sons" business) with a remark to the effect that Richard did a lot of neat and legitimately badass things that we're not going to talk about because they don't fit the narrative plan of the work, Biondi concludes it by saying that Richard was "a prince in many respects worthy to have reigned, if he had not reigned," a statement whose logic is wonderfully twisty -- Richard would have been a pretty good king if he hadn't been king, BUT being king made him unworthy to be king. It is fun stuff. I love having shiny new history texts to play with

Also, while we are on the subject of Richard II -- which may, in fact, be the single most redundant statement ever made on this blog -- perhaps you might be interested in perusing his extensive collection of shiny objects. This page was linked on Chaucer's blog recently and it is much with the coolness. Whatever disparities there are in the accounts of Richard II's life and reign, it is clear from every single piece of existing evidence that he was a man who loved his shiny objects.