England's Heroicall Epistles, Part VIII

In case any of you want something to read while not seeing Pirates of the Caribbean. Although this one does have pirates. Well, it doesn't actually have pirates, but it has HYPOTHETICAL pirates. And there are pirates in the footnotes.

This week's installment, as you may have guessed by the pirates,1 is about a particularly popular historical ship: the possibly-long-awaited Suffolk/Margaret exchange. It's pretty fun. Suffolk's letter is almost entirely about how awesome he is. Though, sadly, he does not say much about his prancing skills, he does talk about ravishing King Henry's ears with his tongue. Seriously.

Also, you may notice that there are now all sorts of links within the text. I've figured out how to do html footnotes on LJ! This means that if you click them, they'll take you down to the notes, and then you can click "Back to text" to go back to where you were. This also makes it easier to see that Drayton needed a better proofreader or something, as the quotes given in the notes don't always match up. I've also added these to the earlier epistles, if any of you are joining us late.

I also wanted to comment on the dedication to this week's epistle. Elizabeth Tanfield, the dedicatee, was in her early teens at the time of publication. At the time this edition of the Epistles was issued, she had already published a translation of Abraham Ortelius' Le miroir du monde, so Drayton's remarks about her intelligence aren't just poetic embellishment. A few years later, she married Henry Cary, Viscount Falkland, and had an unhappy marriage but a fairly awesome writing career. (The family had numerous literary connections: the Lucius Cary apostrophized in Ben Jonson's Cary-Morison ode was their son.) She is best known today as the author of The Tragedy of Mariam, the Fair Queen of Jewry, the first English play known to have been written by a woman; it isn't as widely known but she is, in all likelihood, also the first woman to have written a prose English history, as she is generally acknowledged to be the author of The History of the Life, Reign, and Death of Edward II, published in 1680 (though probably written circa 1627). In general, she was Full of Awesome and one of my favorite people. Also, she's first in line for a Better Know a Poet feature, when I reboot it. Watch this space!

And now back to our regularly scheduled programming...

To my honored mistress, Mistress Elizabeth Tanfield, the sole daughter and heir of that famous and learned lawyer, Lawrence Tanfield Esquire.

Fair and virtuous mistress, since first it was my good fortune to be a witness of the many rare perfections wherewith nature and education have adorned you, I have been forced since that time to attribute more admiration to your sex than ever Petrarch could before persuade me so by the praises of his Laura. Sweet is the French tongue, more sweet the Italian, but most sweet are they both if spoken by your admired self. If poesy were praiseless, your virtues alone were a subject sufficient to make it esteemed, though among the barbarous Geats; by how much the more your tender years give scarcely warrant for your more than womanlike wisdom, by so much is your judgment and reading the more to be wondered at. The Graces shall have one more sister by yourself, and England to herself shall add one Muse more to the Muses. I rest the humble devoted servant to my dear and modest mistress, to whom I wish the happiest fortunes I can devise.

Michael Drayton.

William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk, to Queen Margaret

The Argument.

William de la Pole, first marquess, and after created Duke of Suffolk, being sent into France by King Henry the Sixth, concludeth a marriage between the King his master and Margaret, daughter to Reignier, Duke of Anjou, who only had the title of King of Sicily and Jerusalem. This marriage being made contrary to the liking of the lords and council of the realm, by reason of the yielding up Anjou and Maine into the Duke's hands, which shortly after proved the loss of all Aquitaine, they ever after continually hated the Duke, and after, by means of the commons, banished him at the parliament at Berry, where, after he had the judgment of his exile, being then ready to depart, he writeth back to the Queen this epistle.

In my disgrace, dear Queen, rest thy content,

And Margaret's health from Suffolk's banishment;

Not one day seems five years' exile to me

But that so soon I must depart from thee;

Where thou not present, it is ever night;

All be exiled that live not in thy sight.

Those savages that worship the sun's rise

Would hate their god, if they beheld thine eyes;

The world's great light, might'st thou be seen abroad,

Would at our noon-stead ever make abode,

And make the poor Antipodes to mourn,

Fearing lest he would nevermore return.

Were't not for thee, it were my great'st exile

To live within this sea-environed isle.

Pole's courage brooks not limiting in bands

But that, great Queen, thy sovereignty commands;

Our falcon's kind cannot the cage endure,

Nor, buzzard-like, doth stoop to every lure;

Their mounting brood in open air doth rove,

Nor will with crows be cooped within a grove;

We all do breathe upon this earthly ball;

Likewise one heaven encompasseth us all:

No banishment can be to him assigned

Who doth retain a true resolvèd mind.

Man in himself a little world doth bear,

His soul the monarch ever ruling there;

Wherever, then, his body doth remain,

He is a king that in himself doth reign,

And never feareth Fortune's hott'st alarms,

That beares against her Patience for his arms.

This was the mean proud Warwick did invent

To my disgrace at Leicester Parliament,

That only my base yielding up of Maine

Should be the loss of fertile Aquitaine,

With the base vulgar sort to win him fame

To be the heir of Good Duke Humphrey's name,

And so by treason spotting my pure blood,

Make this a mean to raise the Nevilles' brood.

With Salisbury, his vile ambitious sire,

In York's stern breast kindling long-hidden fire,

By Clarence' title working to supplant

The eagle-aerie of great John of Gaunt.

And to this end my exile did conclude,

Thereby to please the rascal multitude,

Urged by these envious lords to spend their breath,

Calling revenge on the Protector's death,

That since the old decrepit Duke is dead,

By me of force he must be murderèd.

If they would know who robbed him of his life,

Let them call home Dame Eleanor his wife,

Who with a taper walkèd in a sheet

To light her shame at noon through London street,

And let her bring her necromantic book,

That foul hag Jourdaine, Hume, and Bolingbroke,

And let them call the spirits from hell again,

To know how Humphrey died, and who shall reign.

For twenty years and have I served in France,

Against great Charles, and bastard Orleance,

And seen the slaughter of a world of men,

Victorious now, and conquerèd again,

And have I seen Vernoila's battlefields

Strewed with ten thousand helms, ten thousand shields,

Where famous Bedford did our fortune try,

Or France or England for the victory,

The sad investing of so many towns

Scored on my breast in honorable wounds,

When Montacute and Talbot of such name

Under my ensign both won first their fame,

In heat and cold all fortunes have endured

To rouse the French, within their walls immured --

Through all my life these perils have I past

And now to fear a banishment at last?

Thou know'st how I, thy beauty to advance,

For thee refused the infant Queen of France,

Brake the contract Duke Humphrey first did make

'Twixt Henry and the Princess Arminake;

Only, sweet Queen, thy presence I might gain

I gave Duke Reignier Anjou, Mans, and Maine,

Thy peerless beauty for a dower to bring

To counterpoise the wealth of England's King,

And from Aumerle withdrew my warlike powers

And came myself in person first to Towers

Th'ambassadors for truce to entertain

From Belgia, Denmark, Hungary, and Spain;

And, telling Henry of thy beauty's story,

I taught myself a lover's oratory,

As the report itself did so indite

And make tongues ravish ears with their delight,

And when my speech did cease, as telling all,

My looks showed more that was angelical.

And when I breathed again, and pausèd next,

I left mine eyes to comment on the text;

Then, coming of thy modesty to tell,

In music's numbers my voice rose and fell;

And when I came to paint thy glorious style,

My speech in greater cadences to file,

By true descent to wear the diadem

Of Naples, Sicils, and Jerusalem.

And from the gods thou didst derive thy birth,

If heavenly kind could join with brood of earth,

Gracing each title that I did recite

With some mellifluous pleasing epithite,

Nor left him not, till he for love was sick,

Beholding thee in my sweet rhetoric.

A fifteen's tax in France I freely spent

In triumphs at thy nuptial tournament,

And solemnized thy marriage in a gown

Valued at more than was they father's crown,

And, only striving how to honor thee,

Gave to my King what thy love gave to me.

Judge if his kindness have not power to move

Who, for his love's sake, gave away his love.

Had he which once the prize to Greece did bring,

Of whom old poets long ago did sing,

Seen thee for England but embarqued at Deepe,

Would overboard have cast his golden sheep

As too unworthy ballast to be thought

To pester room with such perfection fraught.

The briny seas which saw the ship enfold thee

Would vault up to the hatches to behold thee,

And, falling back, themselves in thronging smother,

Breaking for grief, envying one another,

When the proud bark for joy thy steps to feel

Scorned the salt waves should kiss her furrowing keel,

And, tricked in all her flags, herself she braves,

Cap'ring for joy upon the silver waves,

When like a bull, from the Phoenician strand,

Jove with Europa, tripping from the land

Upon the bosom of the main doth scud

And with his swannish breast cleaving the flood,

Towards the fair fields upon the other side

Beareth Agenor's joy, Phoenicia's pride.

All heavenly beauties join themselves in one

To shew their glory in thine eye alone;

Which, when it turneth that celestial ball,

A thousand sweet stars rise, a thousand fall.

Who justly saith mine banishment to be,

When only France for my recourse is free?

To view the plains where I have seen so oft

England's victorious engines raised aloft;

When this shall be my comfort in my way

To see the place where I may boldly say,

"Here mighty Bedford forth the vaward led;

Here Talbot charged, and here the Frenchmen fled.

Here with our archers valiant Scales did lie.

Here stood the tents of famous Willoughby;

Here Montacute ranged his unconquered band;

Here forth we marched, and here we made a stand."

What should we stand to mourn and grieve all day

For that which time doth easily take away?

What fortune hurts, let patience only heal,

No wisdom wth extremities to deal;

To know ourselves to come of human birth,

These sad afflictions cross us here on earth,

A tax imposed by heaven's eternal law

To keep our rude rebellious will in awe.

In vain we prize that at so dear a rate

Whose best assurance is a fickle state,

And needless we examine our intent,

When, with prevention, we cannot prevent;

When we ourselves foreseeing cannot shun

That which before with destiny doth run.

Henry hath power, and may my life dispose;

Mine honor mine, that none hath power to lose;

Then be as cheerful, beauteous royal Queen,

As in the court of France we erst have been,

As when arrived in Porchester's fair road

Where for our coming Henry made abode,

When in mine arms I brought thee safe to land

And gave my love to Henry's royal hand,

The happy hours we passèd with the King

At fair Southampton, in long banqueting,

With such content as lodged in Henry's breast

When he to London brought thee from the west

Through golden Cheap, when he in pomp did ride

To Westminster, to entertain his bride.

Notes of the Chronicle History.

Our falcon's kind cannot the cage endure.

He alludes in these verses to the falcon, which was the ancient device of the Poles, comparing the greatness and haughtiness of his spirit to the nature of the bird. [Back to text]

This was the mean proud Warwick did invent

To my disgrace, &c.

The commons, at this Parliament, through Warwick's means, accused Suffolk of treason, and urged the accusation so vehemently that the King was forced to exile him for five years. [Back to text]

That only my base yielding up of Maine

Should be the loss of fertile Aquitaine.

The Duke of Suffolk, being sent into France to conclude a peace, chose Duke Reignier's daughter, the Lady Margaret, whom he espoused for Henry the Sixth, delivering for her to her father the countries of Anjou and Maine, and the city of Mans. Whereupon the Earl of Armagnac, whose daughter was before promised to the King, seeing himself to be deluded, caused all the Englishmen to be expulsed Aquitaine, Gascoigne, and Guienne. [Back to text]

With the base vulgar sort to win him fame,

To be the heir of Good Duke Humphrey's name.

This Richard, that was called the great Earl of Warwick, when Duke Humphrey was dead, grew into exceeding great favor with the commons. [Back to text]

With Salisbury, his vile ambitious sire,

In York's stern breast kindling long-hidden fire,

By Clarence' title working to supplant

The eagle-aerie of great John of Gaunt.

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, in the time of Henry the Sixth, claimed the crown, being assisted by this Richard Neville Earl of Salisbury, and father to the great Earl of Warwick, who favored exceedingly the house of York, in open Parliament, as heir to Lionel Duke of Clarence, the third son of Edward the Third, making his title by Anne, his mother, wife to Richard Earl of Cambridge, son to Edmund Langley, Duke of York, which Anne was daughter to Roger Mortimer Earl of March, which Roger was son and heir to Edmund Mortimer that married the Lady Philip, daughter and heir to Lionel Duke of Clarence, the third son of King Edward, to whom the crown after Richard the Second's death lineally descended, he dying without issue, and not to the heirs of the Duke of Lancaster, that was younger brother to the Duke of Clarence. (Hall cap. 1. Tit. Yor. &. Lanc.) [Back to text]

Urged by these envious lords to spend their breath

Calling revenge on the Protector's death.

Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, and Lord Protector, in the twenty-fifth year of Henry the Sixth, by the means of the Queen and the Duke of Suffolk, was arrested by the Lord Beaumont at the Parliament holden in Berri, and the same night after murdered in his bed. [Back to text]

If they would know who robbed him, &c., to this verse,

To know how Humphrey died, and who shall reign.

In these verses he jests at the Protector's wife, who, being accused and convicted of treason, because with John Hume, a priest, Roger Bolingbroke, a necromancer, and Margery Jourdaine, called the Witch of Eye, she had consulted by sorcery to kill the King, was adjudged to perpetual prison in the Isle of Man, and to do penance openly in three public places in London. [Back to text]

For twenty years and have I served in France,

In the sixth year of Henry the Sixth, the Duke of Bedford being deceased, then lieutenant general and regent of France, this Duke of Suffolk was promoted to that dignity, having the Lord Talbot, Lord Scales, and the Lord Montacute to assist him. [Back to text]

Against great Charles, and bastard Orleance.

This was Charles the Seventh, that after the death of Henry the Fifth obtained the crown of France, and recovered again much of that his father had lost. Bastard Orleans was son to the Duke of Orleans, begotten of the Lord Cauny's wife, preferred highly to many notable offices, because he, being a most valiant captain, was continual enemy to the Englishmen, daily infesting them with divers incursions. [Back to text]

And have I seen Vernoila's battlefields,

Vernoil is that noted place in France where the great battle was fought in the beginning of Henry the Sixth's reign, where the most of the French chivalry were overcome by the Duke of Bedford. [Back to text]

And from Aumerle withdrew my warlike powers,

Aumerle is that strong-defensed town in France, which the Duke of Suffolk got after twenty-four great assaults given unto it. [Back to text]

And came myself in person first to Towers

Th'ambassadors for truce to entertain

From Belgia, Denmark, Hungary, and Spain.

Towers [or Tours; I've retained the archaic spelling for the sake of the rhyme -- ed.] is a city in France, built by Brutus as he came into Britain, where, in the twenty-and-one year of the reign of Henry the Sixth, was appointed a great diet to be kept, whither came the ambassadors of the Empire, Spain, Hungary, and Denmark, to entreat for a perpetual peace to be made between the two kings of England and France. [Back to text]

By true descent to wear the diadem

Of Naples, Sicile, and Jerusalem.

Reignier Duke of Anjou, father to Queen Margaret, called himself King of Naples, Sicily, and Jerusalem, having the title alone of king of those countries. [Back to text]

A fifteen's tax in France I freely spent,

The Duke of Suffolk, after the marriage concluded 'twixt King Henry and Margaret, daughter to Duke Reignier, asked in open Parliament a whole fifteenth to fetch her into England. [Back to text]

Seen thee for England but embarqued at Deepe.

Deepe [Dieppe; again, the archaic spelling preserves the rhyme -- ed.] is a town in France, bordering upon the sea, where the Duke of Suffolk with Queen Margaret took ship for England. [Back to text]

As when arrived in Porchester's fair road.

Porchester, a haven town in the southwest part of England, where the King tarried, expecting the Queen's arrival, whom from thence he conveyed to Southampton. [Back to text]

Queen Margaret to William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk.

What news, sweet Pole, look'st thou my lines should tell,

But like the sounding of the doleful bell,

Bidding the deathsman to prepare the grave?

Expect from me no other news to have;

My breast, which once was mirth's imperial throne,

A vast and desert wilderness is grown,

Like that cold region, from the world remote,

On whose breem seas the icy mountains float,

Where those poor creatures banished from the light

Do live imprisoned in continual night.

No joy presents my soul's internal eyes

But divination of sad tragedies,

And care takes up her solitary inn

Where youth and joy their court did once begin.

As in September, when our year resigns

The glorious sun unto the watery signs,

Which through the clouds looks on the earth in scorn,

The little bird, yet to salute the morn,

Upon the naked branches sets her foot,

The leaves now lying on the mossy root,

And there a silly chirruping doth keep,

As though she fain would sing, yet fain would weep,

Praising fair summer, that too soon is gone,

Or mourning winter, too fast coming on.

In this sad plight I mourn for thy depart,

Because that weeping cannot ease my heart.

Now to our aid who stirs the neighboring kings?

Or who from France a puissant army brings?

Who moves the Norman to abet our war,

Or stirs up Burgoigne to aid Lancaster?

Who in the North our lawful claim commends

To win us credit with our valiant friends?

To whom shall I my secret grief impart,

Whose breast I made the closet of my heart?

The ancient heroes' fame thou didst revive,

And didst from them thy memory derive;

Nature by thee both gave and taketh all;

Alone in Pole she was too prodigal;

Of so divine and rich a temper wrought,

As heaven for him perfection's depth had sought.

Well knew King Henry what he pleaded for

When thou wert made his sweet-tongued orator,

Whose angel eye, by powerful influence,

Doth utter more than human eloquence,

That when Jove would his youthful sports have tried,

But in thy shape, himself would never hide,

Which in his love had been of greater power

Than was his nymph, his flame, his swan, his shower.

To that allegiance York was bound by oath

To Henry's heirs, and safety of us both;

No longer now he means record shall bear it,

He will dispense with heaven, and will unswear it.

He that's in all the world's black sins forlorn

Is careless now how oft he be forsworn,

And now of late his title hath set down

By which he makes his claim unto the crown.

And now I hear his hateful duchess chats

And rips up their descent unto her brats,

And blesseth them as England's lawful heirs,

And tells them that our diadem is theirs,

And if such hap her goddess Fortune bring,

If three sons fail, she'll make the fourth a king:

He that's so like his dam, her youngest, Dick,

That foul, ill-favored, crookbacked stigmatic,

That, like a carcass stol'n out of a tomb,

Came the wrong way out of his mother's womb,

With teeth in's head his passage to have torn

As though begot an age ere he was born.

Who now will curb proud York when he shall rise,

Or arms our right against his enterprise

To crop that bastard weed which daily grows

To overshadow our vermilion rose?

Or who will muzzle that unruly bear

Whose presence strikes our people's hearts with fear,

Whilst on his knees this wretched King is down,

To save them labor, reaching at his crown?

Where, like a mounting cedar, he should bear

His plumèd top aloft into the air,

And let these shrubs sit underneath his shrouds

Whilst in his arms he doth embrace the clouds.

O that he should his father's right inherit,

Yet be an alien to that mighty spirit!

How were those powers dispersed, or whither gone,

Should sympathize in generation,

Or what opposèd influence had force

To abuse kind, and alter nature's course?

All other creatures follow after kind,

But man alone doth not beget the mind.

My daisy-flower, which erst perfumed the air,

Which for my favors princes once did wear,

Now in the dust lies trodden on the ground,

And with York's garlands everyone is crowned,

When now his rising waits on our decline,

And in our setting he begins to shine.

Now in the skies that dreadful comet waves,

And who be stars but Warwick's bearded staves?

And all those knees which bended once so low

Grow stiff as if they had forgot to bow;

And none like them pursue me with despite

Which most have cried "God save Queen Margarite!"

When fame shall bruit thy banishment abroad,

The Yorkish faction then will lay on load,

And when it comes once to our western coast,

O how that hag Dame Eleanor will boast,

And labor straight, by all the means she can,

To be called home out of the Isle of Man,

To which I know great Warwick will consent

To have it done by act of Parliament,

That to my teeth my birth she may defy,

Sland'ring Duke Reignier with base beggary;

The only way she could devise to grieve me,

Wanting sweet Suffolk, which should most relieve me.

And from that stock doth sprout another bloom,

A Kentish rebel, a base upstart groom,

And this is he the white rose must prefer

By Clarence' daughter, matched with Mortimer.

Thus by York's means this rascal peasant Cade

Must in all haste Plantagenet be made;

Thus that ambitious duke sets all on work

To sound what friends affect the claim of York,

Whilst he abroad doth practice to command,

And makes us weak by strengthening Ireland,

More his own power still seeking to increase

Than for King Henry's good, or England's peace.

Great Winchester untimely is deceased,

That more and more my woes should be increased.

Beaufort, whose shoulders proudly bare up all,

The Church's prop, that famous cardinal,

The commons, bent to mischief, never let,

With France t'upbraid that valiant Somerset,

Railing in tumults on his soldiers' loss,

Thus all goes backward, cross comes after cross.

And now of late Duke Humphrey's old allies,

With banished El'nor's base accomplices,

Attending their revenge, grow wondrous crouse,

And threaten death and vengeance to our house,

And I alone the woeful remnant am,

T'endure these storms with woeful Buckingham.

I pray thee, Pole, have care how thou dost pass;

Never the sea yet half so dangerous was,

And one foretold by water thou should'st die --

Ah, foul befall that foul tongue's prophecy! --

And every night am troubled in my dreams

That I do see thee tossed in dangerous streams,

And oft-times shipwracked, cast upon the land,

And lying breathless on the queachy sand;

And oft in visions see thee in the night,

Where thou at sea maintain'st a dangerous fight,

And with thy provèd target and thy sword

Beat'st back the pirate which would come aboard.

Yet be not angry that I warn thee thus;

The truest love is most suspicious;

Sorrow doth utter what us still doth grieve,

But hope forbids us sorrow to believe.

And in my counsel yet this comfort is:

It cannot hurt, although I think amiss;

Then live in hope, in triumph to return,

When clearer days shall leave in clouds to mourn;

But so hath sorrow girt my soul about

That that word hope, methinks, come slowly out;

The reason is, I know it here would rest

Where it may still behold thee in my breast.

Farewell, sweet Pole; fain more I would indite,

But that my tears do blot as I do write.

Notes of the Chronicle History.

Or brings in Burgoigne to aid Lancaster.

Philip Duke of Burgoigne and his son were always great favorites of the house of Lancaster, howbeit they often dissembled both with Lancaster and York. [Back to text]

Who in the North our lawful claim commends

To win us credit with our valiant friends?

The chief lords of the north parts, in the time of Henry VI, withstood the Duke of York at his rising, giving him two great overthrows. [Back to text]

To that allegiance York was bound by oath

To Henry's heirs, and safety of us both.

No longer now he means records shall bear it;

He will dispense with heaven, and will unswear it.

The Duke of York, at the death of Henry the Fifth, and at this king's coronation, took his oath to be true subject to him and his heirs forever, but afterward dispensing therewith, claimed the crown as his rightful and proper inheritance. [Back to text]

If three sons fail, she'll make the fourth a king.

The Duke of York had four sons: Edward, Earl of March, that afterwards was Duke of York, and King of England, when he had deposed Henry the Sixth; and Edmund, Earl of Rutland, slain by the Lord Clifford at the Battle of Wakefield; and George, Duke of Clarence, that was murdered in the Tower; and Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who was, after he had murdered his brother's sons, king by the name of Richard the Third. [Back to text]

He that's so like his dam, her youngest, Dick,

That foul, ill-favored, crookbacked stigmatic, &c.

Till this verse, As though begot an age, &c.

This Richard, whom ironically she calls Dick, that by treason after his nephews murdered, obtained the crown, was a man low of stature, crookbacked, the left shoulder much higher than the right, and of a very crabbed and sour countenance; his mother could not be delivered of him, he was born toothed, and with his feet forward, contrary to the course of nature. [Back to text]

To overshadow our vermilion rose.

The red rose was the badge of the house of Lancaster, and the white rose of York, which by the marriage of Henry the Seventh with Elizabeth, indubitate heir of the house of York, was conjoined and united. [Back to text]

Or who will muzzle that unruly bear,

The Earl of Warwick, the setter-up and puller-down of kings, gave for his arms the white bear rampant, and the ragged staff. [Back to text]

My daisy-flower which erst perfumed the air,

Which for my favor princes once did wear, &c.

The daisy in French is called Marguerite, which was Queen Margaret's badge, wherewithal the nobility and chivalry of the land at the first arrival were so delighted, that they wore it in their hats in token of honor. [Back to text]

And who be stars but Warwick's bearded staves?

The ragged or bearded staff was a part of the arms belonging to the earldom of Warwick. [Back to text]

Sland'ring Duke Reignier with base beggary.

Reignier, Duke of Anjou, called himself King of Naples, Sicile, and Jerusalem, having neither inheritance nor tribute from those parts, and was not able, at the marriage of the Queen, of his own charges to send her into England though he gave no dower with her, which by the Duchess of Gloucester was often in disgrace cast in her teeth. [Back to text]

A Kentish rebel, a base upstart groom.

This was Jack Cade, which caused the Kentishmen to rebel in the twenty-eighth year of Henry the Sixth. [Back to text]

And this is he the white rose must prefer

By Clarence' daughter matched to Mortimer.

This Jack Cade, instructed by the Duke of York, pretended to be descended from Mortimer which married Lady Philip, daughter to the Duke of Clarence. [Back to text]

And makes us weak by strength'ning Ireland.

The Duke of York, being made deputy of Ireland, first there began to practice his long-intended purpose, strengthening himself by all means possible that he might at his return into England by open war claim that which so long he had privily gone about to obtain. [Back to text]

Great Winchester untimely is deceased.

Henry Beaufort, Bishop and Cardinal of Winchester, son to John of Gaunt begot in his age, was a proud and ambitious prelate, favoring mightily the Queen and the Duke of Suffolk, continually heaping up innumerable treasure, in hope to have been Pope, as himself on his deathbed confessed. [Back to text]

With France t'upbraid the valiant Somerset.

Edmund Duke of Somerset, in the twenty-fourth of Henry the Sixth, was made Regent of France, and sent into Normandy to defend the English territories against the French invasions, but in short time he lost all that King Henry the Fifth won, for which cause the nobles and the commons ever after hated him. [Back to text]

T'endure these storms with woeful Buckingham.

Humphrey, Duke of Buckingham, was a great favorite of the Queen's faction, in the time of Henry the Sixth. [Back to text]

And one foretold by water thou should'st die.

The Witch of Eye received answer by her spirit that the Duke of Suffolk should take heed of water; which the Queen forewarns him of, as remembering the witch's prophecy, which afterward came to pass. [According to tradition, the pirate who killed Suffolk was named Walter, which -- as the poetry of Sir Walter Ralegh indicates -- was often pronounced in the past without an audible L. Shakespeare gives him the surname of Whitmore -- ed.] [Back to text]

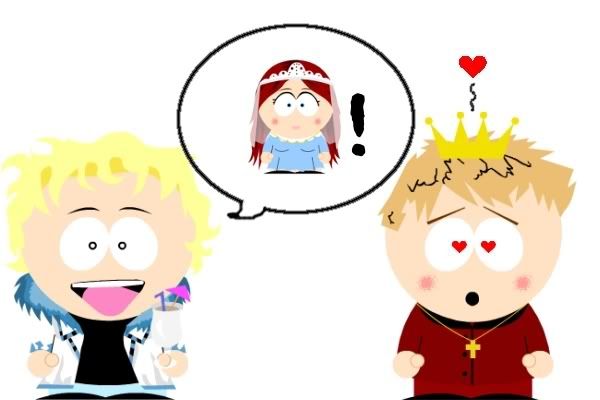

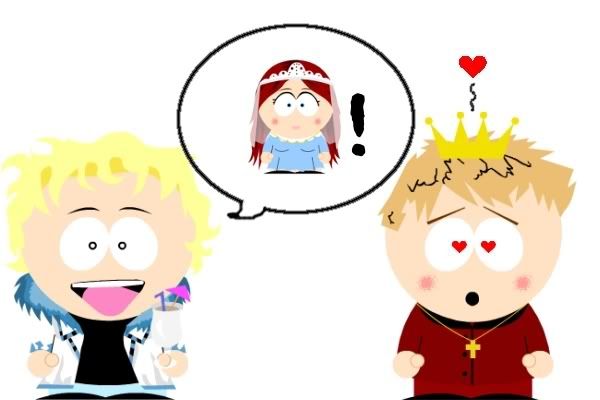

Also, this installment comes with a bonus illustration!

"And, telling Henry of thy beauty's story,

I taught myself a lover's oratory

...Nor left him not, till he for love was sick,

Beholding thee in my sweet rhetoric."

That was fun. I may have to go back and do them for other epistles. ;)

NEXT TIME: Edward IV is a mack daddy. This makes him unworthy of footnotes, but Jane Shore is impressed. But she's only going to put out because he's the King, you know.

1. The only other significant couple from this general period in English history I can think of who has a Notable Pirate Encounter are Henry IV and Joan of Navarre, and we're already past them, besides which they're never in stuff like this anyway. Here's the real thing instead. No pirates, though.

This week's installment, as you may have guessed by the pirates,1 is about a particularly popular historical ship: the possibly-long-awaited Suffolk/Margaret exchange. It's pretty fun. Suffolk's letter is almost entirely about how awesome he is. Though, sadly, he does not say much about his prancing skills, he does talk about ravishing King Henry's ears with his tongue. Seriously.

Also, you may notice that there are now all sorts of links within the text. I've figured out how to do html footnotes on LJ! This means that if you click them, they'll take you down to the notes, and then you can click "Back to text" to go back to where you were. This also makes it easier to see that Drayton needed a better proofreader or something, as the quotes given in the notes don't always match up. I've also added these to the earlier epistles, if any of you are joining us late.

I also wanted to comment on the dedication to this week's epistle. Elizabeth Tanfield, the dedicatee, was in her early teens at the time of publication. At the time this edition of the Epistles was issued, she had already published a translation of Abraham Ortelius' Le miroir du monde, so Drayton's remarks about her intelligence aren't just poetic embellishment. A few years later, she married Henry Cary, Viscount Falkland, and had an unhappy marriage but a fairly awesome writing career. (The family had numerous literary connections: the Lucius Cary apostrophized in Ben Jonson's Cary-Morison ode was their son.) She is best known today as the author of The Tragedy of Mariam, the Fair Queen of Jewry, the first English play known to have been written by a woman; it isn't as widely known but she is, in all likelihood, also the first woman to have written a prose English history, as she is generally acknowledged to be the author of The History of the Life, Reign, and Death of Edward II, published in 1680 (though probably written circa 1627). In general, she was Full of Awesome and one of my favorite people. Also, she's first in line for a Better Know a Poet feature, when I reboot it. Watch this space!

And now back to our regularly scheduled programming...

To my honored mistress, Mistress Elizabeth Tanfield, the sole daughter and heir of that famous and learned lawyer, Lawrence Tanfield Esquire.

Fair and virtuous mistress, since first it was my good fortune to be a witness of the many rare perfections wherewith nature and education have adorned you, I have been forced since that time to attribute more admiration to your sex than ever Petrarch could before persuade me so by the praises of his Laura. Sweet is the French tongue, more sweet the Italian, but most sweet are they both if spoken by your admired self. If poesy were praiseless, your virtues alone were a subject sufficient to make it esteemed, though among the barbarous Geats; by how much the more your tender years give scarcely warrant for your more than womanlike wisdom, by so much is your judgment and reading the more to be wondered at. The Graces shall have one more sister by yourself, and England to herself shall add one Muse more to the Muses. I rest the humble devoted servant to my dear and modest mistress, to whom I wish the happiest fortunes I can devise.

Michael Drayton.

William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk, to Queen Margaret

The Argument.

William de la Pole, first marquess, and after created Duke of Suffolk, being sent into France by King Henry the Sixth, concludeth a marriage between the King his master and Margaret, daughter to Reignier, Duke of Anjou, who only had the title of King of Sicily and Jerusalem. This marriage being made contrary to the liking of the lords and council of the realm, by reason of the yielding up Anjou and Maine into the Duke's hands, which shortly after proved the loss of all Aquitaine, they ever after continually hated the Duke, and after, by means of the commons, banished him at the parliament at Berry, where, after he had the judgment of his exile, being then ready to depart, he writeth back to the Queen this epistle.

In my disgrace, dear Queen, rest thy content,

And Margaret's health from Suffolk's banishment;

Not one day seems five years' exile to me

But that so soon I must depart from thee;

Where thou not present, it is ever night;

All be exiled that live not in thy sight.

Those savages that worship the sun's rise

Would hate their god, if they beheld thine eyes;

The world's great light, might'st thou be seen abroad,

Would at our noon-stead ever make abode,

And make the poor Antipodes to mourn,

Fearing lest he would nevermore return.

Were't not for thee, it were my great'st exile

To live within this sea-environed isle.

Pole's courage brooks not limiting in bands

But that, great Queen, thy sovereignty commands;

Our falcon's kind cannot the cage endure,

Nor, buzzard-like, doth stoop to every lure;

Their mounting brood in open air doth rove,

Nor will with crows be cooped within a grove;

We all do breathe upon this earthly ball;

Likewise one heaven encompasseth us all:

No banishment can be to him assigned

Who doth retain a true resolvèd mind.

Man in himself a little world doth bear,

His soul the monarch ever ruling there;

Wherever, then, his body doth remain,

He is a king that in himself doth reign,

And never feareth Fortune's hott'st alarms,

That beares against her Patience for his arms.

This was the mean proud Warwick did invent

To my disgrace at Leicester Parliament,

That only my base yielding up of Maine

Should be the loss of fertile Aquitaine,

With the base vulgar sort to win him fame

To be the heir of Good Duke Humphrey's name,

And so by treason spotting my pure blood,

Make this a mean to raise the Nevilles' brood.

With Salisbury, his vile ambitious sire,

In York's stern breast kindling long-hidden fire,

By Clarence' title working to supplant

The eagle-aerie of great John of Gaunt.

And to this end my exile did conclude,

Thereby to please the rascal multitude,

Urged by these envious lords to spend their breath,

Calling revenge on the Protector's death,

That since the old decrepit Duke is dead,

By me of force he must be murderèd.

If they would know who robbed him of his life,

Let them call home Dame Eleanor his wife,

Who with a taper walkèd in a sheet

To light her shame at noon through London street,

And let her bring her necromantic book,

That foul hag Jourdaine, Hume, and Bolingbroke,

And let them call the spirits from hell again,

To know how Humphrey died, and who shall reign.

For twenty years and have I served in France,

Against great Charles, and bastard Orleance,

And seen the slaughter of a world of men,

Victorious now, and conquerèd again,

And have I seen Vernoila's battlefields

Strewed with ten thousand helms, ten thousand shields,

Where famous Bedford did our fortune try,

Or France or England for the victory,

The sad investing of so many towns

Scored on my breast in honorable wounds,

When Montacute and Talbot of such name

Under my ensign both won first their fame,

In heat and cold all fortunes have endured

To rouse the French, within their walls immured --

Through all my life these perils have I past

And now to fear a banishment at last?

Thou know'st how I, thy beauty to advance,

For thee refused the infant Queen of France,

Brake the contract Duke Humphrey first did make

'Twixt Henry and the Princess Arminake;

Only, sweet Queen, thy presence I might gain

I gave Duke Reignier Anjou, Mans, and Maine,

Thy peerless beauty for a dower to bring

To counterpoise the wealth of England's King,

And from Aumerle withdrew my warlike powers

And came myself in person first to Towers

Th'ambassadors for truce to entertain

From Belgia, Denmark, Hungary, and Spain;

And, telling Henry of thy beauty's story,

I taught myself a lover's oratory,

As the report itself did so indite

And make tongues ravish ears with their delight,

And when my speech did cease, as telling all,

My looks showed more that was angelical.

And when I breathed again, and pausèd next,

I left mine eyes to comment on the text;

Then, coming of thy modesty to tell,

In music's numbers my voice rose and fell;

And when I came to paint thy glorious style,

My speech in greater cadences to file,

By true descent to wear the diadem

Of Naples, Sicils, and Jerusalem.

And from the gods thou didst derive thy birth,

If heavenly kind could join with brood of earth,

Gracing each title that I did recite

With some mellifluous pleasing epithite,

Nor left him not, till he for love was sick,

Beholding thee in my sweet rhetoric.

A fifteen's tax in France I freely spent

In triumphs at thy nuptial tournament,

And solemnized thy marriage in a gown

Valued at more than was they father's crown,

And, only striving how to honor thee,

Gave to my King what thy love gave to me.

Judge if his kindness have not power to move

Who, for his love's sake, gave away his love.

Had he which once the prize to Greece did bring,

Of whom old poets long ago did sing,

Seen thee for England but embarqued at Deepe,

Would overboard have cast his golden sheep

As too unworthy ballast to be thought

To pester room with such perfection fraught.

The briny seas which saw the ship enfold thee

Would vault up to the hatches to behold thee,

And, falling back, themselves in thronging smother,

Breaking for grief, envying one another,

When the proud bark for joy thy steps to feel

Scorned the salt waves should kiss her furrowing keel,

And, tricked in all her flags, herself she braves,

Cap'ring for joy upon the silver waves,

When like a bull, from the Phoenician strand,

Jove with Europa, tripping from the land

Upon the bosom of the main doth scud

And with his swannish breast cleaving the flood,

Towards the fair fields upon the other side

Beareth Agenor's joy, Phoenicia's pride.

All heavenly beauties join themselves in one

To shew their glory in thine eye alone;

Which, when it turneth that celestial ball,

A thousand sweet stars rise, a thousand fall.

Who justly saith mine banishment to be,

When only France for my recourse is free?

To view the plains where I have seen so oft

England's victorious engines raised aloft;

When this shall be my comfort in my way

To see the place where I may boldly say,

"Here mighty Bedford forth the vaward led;

Here Talbot charged, and here the Frenchmen fled.

Here with our archers valiant Scales did lie.

Here stood the tents of famous Willoughby;

Here Montacute ranged his unconquered band;

Here forth we marched, and here we made a stand."

What should we stand to mourn and grieve all day

For that which time doth easily take away?

What fortune hurts, let patience only heal,

No wisdom wth extremities to deal;

To know ourselves to come of human birth,

These sad afflictions cross us here on earth,

A tax imposed by heaven's eternal law

To keep our rude rebellious will in awe.

In vain we prize that at so dear a rate

Whose best assurance is a fickle state,

And needless we examine our intent,

When, with prevention, we cannot prevent;

When we ourselves foreseeing cannot shun

That which before with destiny doth run.

Henry hath power, and may my life dispose;

Mine honor mine, that none hath power to lose;

Then be as cheerful, beauteous royal Queen,

As in the court of France we erst have been,

As when arrived in Porchester's fair road

Where for our coming Henry made abode,

When in mine arms I brought thee safe to land

And gave my love to Henry's royal hand,

The happy hours we passèd with the King

At fair Southampton, in long banqueting,

With such content as lodged in Henry's breast

When he to London brought thee from the west

Through golden Cheap, when he in pomp did ride

To Westminster, to entertain his bride.

Notes of the Chronicle History.

Our falcon's kind cannot the cage endure.

He alludes in these verses to the falcon, which was the ancient device of the Poles, comparing the greatness and haughtiness of his spirit to the nature of the bird. [Back to text]

This was the mean proud Warwick did invent

To my disgrace, &c.

The commons, at this Parliament, through Warwick's means, accused Suffolk of treason, and urged the accusation so vehemently that the King was forced to exile him for five years. [Back to text]

That only my base yielding up of Maine

Should be the loss of fertile Aquitaine.

The Duke of Suffolk, being sent into France to conclude a peace, chose Duke Reignier's daughter, the Lady Margaret, whom he espoused for Henry the Sixth, delivering for her to her father the countries of Anjou and Maine, and the city of Mans. Whereupon the Earl of Armagnac, whose daughter was before promised to the King, seeing himself to be deluded, caused all the Englishmen to be expulsed Aquitaine, Gascoigne, and Guienne. [Back to text]

With the base vulgar sort to win him fame,

To be the heir of Good Duke Humphrey's name.

This Richard, that was called the great Earl of Warwick, when Duke Humphrey was dead, grew into exceeding great favor with the commons. [Back to text]

With Salisbury, his vile ambitious sire,

In York's stern breast kindling long-hidden fire,

By Clarence' title working to supplant

The eagle-aerie of great John of Gaunt.

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, in the time of Henry the Sixth, claimed the crown, being assisted by this Richard Neville Earl of Salisbury, and father to the great Earl of Warwick, who favored exceedingly the house of York, in open Parliament, as heir to Lionel Duke of Clarence, the third son of Edward the Third, making his title by Anne, his mother, wife to Richard Earl of Cambridge, son to Edmund Langley, Duke of York, which Anne was daughter to Roger Mortimer Earl of March, which Roger was son and heir to Edmund Mortimer that married the Lady Philip, daughter and heir to Lionel Duke of Clarence, the third son of King Edward, to whom the crown after Richard the Second's death lineally descended, he dying without issue, and not to the heirs of the Duke of Lancaster, that was younger brother to the Duke of Clarence. (Hall cap. 1. Tit. Yor. &. Lanc.) [Back to text]

Urged by these envious lords to spend their breath

Calling revenge on the Protector's death.

Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, and Lord Protector, in the twenty-fifth year of Henry the Sixth, by the means of the Queen and the Duke of Suffolk, was arrested by the Lord Beaumont at the Parliament holden in Berri, and the same night after murdered in his bed. [Back to text]

If they would know who robbed him, &c., to this verse,

To know how Humphrey died, and who shall reign.

In these verses he jests at the Protector's wife, who, being accused and convicted of treason, because with John Hume, a priest, Roger Bolingbroke, a necromancer, and Margery Jourdaine, called the Witch of Eye, she had consulted by sorcery to kill the King, was adjudged to perpetual prison in the Isle of Man, and to do penance openly in three public places in London. [Back to text]

For twenty years and have I served in France,

In the sixth year of Henry the Sixth, the Duke of Bedford being deceased, then lieutenant general and regent of France, this Duke of Suffolk was promoted to that dignity, having the Lord Talbot, Lord Scales, and the Lord Montacute to assist him. [Back to text]

Against great Charles, and bastard Orleance.

This was Charles the Seventh, that after the death of Henry the Fifth obtained the crown of France, and recovered again much of that his father had lost. Bastard Orleans was son to the Duke of Orleans, begotten of the Lord Cauny's wife, preferred highly to many notable offices, because he, being a most valiant captain, was continual enemy to the Englishmen, daily infesting them with divers incursions. [Back to text]

And have I seen Vernoila's battlefields,

Vernoil is that noted place in France where the great battle was fought in the beginning of Henry the Sixth's reign, where the most of the French chivalry were overcome by the Duke of Bedford. [Back to text]

And from Aumerle withdrew my warlike powers,

Aumerle is that strong-defensed town in France, which the Duke of Suffolk got after twenty-four great assaults given unto it. [Back to text]

And came myself in person first to Towers

Th'ambassadors for truce to entertain

From Belgia, Denmark, Hungary, and Spain.

Towers [or Tours; I've retained the archaic spelling for the sake of the rhyme -- ed.] is a city in France, built by Brutus as he came into Britain, where, in the twenty-and-one year of the reign of Henry the Sixth, was appointed a great diet to be kept, whither came the ambassadors of the Empire, Spain, Hungary, and Denmark, to entreat for a perpetual peace to be made between the two kings of England and France. [Back to text]

By true descent to wear the diadem

Of Naples, Sicile, and Jerusalem.

Reignier Duke of Anjou, father to Queen Margaret, called himself King of Naples, Sicily, and Jerusalem, having the title alone of king of those countries. [Back to text]

A fifteen's tax in France I freely spent,

The Duke of Suffolk, after the marriage concluded 'twixt King Henry and Margaret, daughter to Duke Reignier, asked in open Parliament a whole fifteenth to fetch her into England. [Back to text]

Seen thee for England but embarqued at Deepe.

Deepe [Dieppe; again, the archaic spelling preserves the rhyme -- ed.] is a town in France, bordering upon the sea, where the Duke of Suffolk with Queen Margaret took ship for England. [Back to text]

As when arrived in Porchester's fair road.

Porchester, a haven town in the southwest part of England, where the King tarried, expecting the Queen's arrival, whom from thence he conveyed to Southampton. [Back to text]

Queen Margaret to William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk.

What news, sweet Pole, look'st thou my lines should tell,

But like the sounding of the doleful bell,

Bidding the deathsman to prepare the grave?

Expect from me no other news to have;

My breast, which once was mirth's imperial throne,

A vast and desert wilderness is grown,

Like that cold region, from the world remote,

On whose breem seas the icy mountains float,

Where those poor creatures banished from the light

Do live imprisoned in continual night.

No joy presents my soul's internal eyes

But divination of sad tragedies,

And care takes up her solitary inn

Where youth and joy their court did once begin.

As in September, when our year resigns

The glorious sun unto the watery signs,

Which through the clouds looks on the earth in scorn,

The little bird, yet to salute the morn,

Upon the naked branches sets her foot,

The leaves now lying on the mossy root,

And there a silly chirruping doth keep,

As though she fain would sing, yet fain would weep,

Praising fair summer, that too soon is gone,

Or mourning winter, too fast coming on.

In this sad plight I mourn for thy depart,

Because that weeping cannot ease my heart.

Now to our aid who stirs the neighboring kings?

Or who from France a puissant army brings?

Who moves the Norman to abet our war,

Or stirs up Burgoigne to aid Lancaster?

Who in the North our lawful claim commends

To win us credit with our valiant friends?

To whom shall I my secret grief impart,

Whose breast I made the closet of my heart?

The ancient heroes' fame thou didst revive,

And didst from them thy memory derive;

Nature by thee both gave and taketh all;

Alone in Pole she was too prodigal;

Of so divine and rich a temper wrought,

As heaven for him perfection's depth had sought.

Well knew King Henry what he pleaded for

When thou wert made his sweet-tongued orator,

Whose angel eye, by powerful influence,

Doth utter more than human eloquence,

That when Jove would his youthful sports have tried,

But in thy shape, himself would never hide,

Which in his love had been of greater power

Than was his nymph, his flame, his swan, his shower.

To that allegiance York was bound by oath

To Henry's heirs, and safety of us both;

No longer now he means record shall bear it,

He will dispense with heaven, and will unswear it.

He that's in all the world's black sins forlorn

Is careless now how oft he be forsworn,

And now of late his title hath set down

By which he makes his claim unto the crown.

And now I hear his hateful duchess chats

And rips up their descent unto her brats,

And blesseth them as England's lawful heirs,

And tells them that our diadem is theirs,

And if such hap her goddess Fortune bring,

If three sons fail, she'll make the fourth a king:

He that's so like his dam, her youngest, Dick,

That foul, ill-favored, crookbacked stigmatic,

That, like a carcass stol'n out of a tomb,

Came the wrong way out of his mother's womb,

With teeth in's head his passage to have torn

As though begot an age ere he was born.

Who now will curb proud York when he shall rise,

Or arms our right against his enterprise

To crop that bastard weed which daily grows

To overshadow our vermilion rose?

Or who will muzzle that unruly bear

Whose presence strikes our people's hearts with fear,

Whilst on his knees this wretched King is down,

To save them labor, reaching at his crown?

Where, like a mounting cedar, he should bear

His plumèd top aloft into the air,

And let these shrubs sit underneath his shrouds

Whilst in his arms he doth embrace the clouds.

O that he should his father's right inherit,

Yet be an alien to that mighty spirit!

How were those powers dispersed, or whither gone,

Should sympathize in generation,

Or what opposèd influence had force

To abuse kind, and alter nature's course?

All other creatures follow after kind,

But man alone doth not beget the mind.

My daisy-flower, which erst perfumed the air,

Which for my favors princes once did wear,

Now in the dust lies trodden on the ground,

And with York's garlands everyone is crowned,

When now his rising waits on our decline,

And in our setting he begins to shine.

Now in the skies that dreadful comet waves,

And who be stars but Warwick's bearded staves?

And all those knees which bended once so low

Grow stiff as if they had forgot to bow;

And none like them pursue me with despite

Which most have cried "God save Queen Margarite!"

When fame shall bruit thy banishment abroad,

The Yorkish faction then will lay on load,

And when it comes once to our western coast,

O how that hag Dame Eleanor will boast,

And labor straight, by all the means she can,

To be called home out of the Isle of Man,

To which I know great Warwick will consent

To have it done by act of Parliament,

That to my teeth my birth she may defy,

Sland'ring Duke Reignier with base beggary;

The only way she could devise to grieve me,

Wanting sweet Suffolk, which should most relieve me.

And from that stock doth sprout another bloom,

A Kentish rebel, a base upstart groom,

And this is he the white rose must prefer

By Clarence' daughter, matched with Mortimer.

Thus by York's means this rascal peasant Cade

Must in all haste Plantagenet be made;

Thus that ambitious duke sets all on work

To sound what friends affect the claim of York,

Whilst he abroad doth practice to command,

And makes us weak by strengthening Ireland,

More his own power still seeking to increase

Than for King Henry's good, or England's peace.

Great Winchester untimely is deceased,

That more and more my woes should be increased.

Beaufort, whose shoulders proudly bare up all,

The Church's prop, that famous cardinal,

The commons, bent to mischief, never let,

With France t'upbraid that valiant Somerset,

Railing in tumults on his soldiers' loss,

Thus all goes backward, cross comes after cross.

And now of late Duke Humphrey's old allies,

With banished El'nor's base accomplices,

Attending their revenge, grow wondrous crouse,

And threaten death and vengeance to our house,

And I alone the woeful remnant am,

T'endure these storms with woeful Buckingham.

I pray thee, Pole, have care how thou dost pass;

Never the sea yet half so dangerous was,

And one foretold by water thou should'st die --

Ah, foul befall that foul tongue's prophecy! --

And every night am troubled in my dreams

That I do see thee tossed in dangerous streams,

And oft-times shipwracked, cast upon the land,

And lying breathless on the queachy sand;

And oft in visions see thee in the night,

Where thou at sea maintain'st a dangerous fight,

And with thy provèd target and thy sword

Beat'st back the pirate which would come aboard.

Yet be not angry that I warn thee thus;

The truest love is most suspicious;

Sorrow doth utter what us still doth grieve,

But hope forbids us sorrow to believe.

And in my counsel yet this comfort is:

It cannot hurt, although I think amiss;

Then live in hope, in triumph to return,

When clearer days shall leave in clouds to mourn;

But so hath sorrow girt my soul about

That that word hope, methinks, come slowly out;

The reason is, I know it here would rest

Where it may still behold thee in my breast.

Farewell, sweet Pole; fain more I would indite,

But that my tears do blot as I do write.

Notes of the Chronicle History.

Or brings in Burgoigne to aid Lancaster.

Philip Duke of Burgoigne and his son were always great favorites of the house of Lancaster, howbeit they often dissembled both with Lancaster and York. [Back to text]

Who in the North our lawful claim commends

To win us credit with our valiant friends?

The chief lords of the north parts, in the time of Henry VI, withstood the Duke of York at his rising, giving him two great overthrows. [Back to text]

To that allegiance York was bound by oath

To Henry's heirs, and safety of us both.

No longer now he means records shall bear it;

He will dispense with heaven, and will unswear it.

The Duke of York, at the death of Henry the Fifth, and at this king's coronation, took his oath to be true subject to him and his heirs forever, but afterward dispensing therewith, claimed the crown as his rightful and proper inheritance. [Back to text]

If three sons fail, she'll make the fourth a king.

The Duke of York had four sons: Edward, Earl of March, that afterwards was Duke of York, and King of England, when he had deposed Henry the Sixth; and Edmund, Earl of Rutland, slain by the Lord Clifford at the Battle of Wakefield; and George, Duke of Clarence, that was murdered in the Tower; and Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who was, after he had murdered his brother's sons, king by the name of Richard the Third. [Back to text]

He that's so like his dam, her youngest, Dick,

That foul, ill-favored, crookbacked stigmatic, &c.

Till this verse, As though begot an age, &c.

This Richard, whom ironically she calls Dick, that by treason after his nephews murdered, obtained the crown, was a man low of stature, crookbacked, the left shoulder much higher than the right, and of a very crabbed and sour countenance; his mother could not be delivered of him, he was born toothed, and with his feet forward, contrary to the course of nature. [Back to text]

To overshadow our vermilion rose.

The red rose was the badge of the house of Lancaster, and the white rose of York, which by the marriage of Henry the Seventh with Elizabeth, indubitate heir of the house of York, was conjoined and united. [Back to text]

Or who will muzzle that unruly bear,

The Earl of Warwick, the setter-up and puller-down of kings, gave for his arms the white bear rampant, and the ragged staff. [Back to text]

My daisy-flower which erst perfumed the air,

Which for my favor princes once did wear, &c.

The daisy in French is called Marguerite, which was Queen Margaret's badge, wherewithal the nobility and chivalry of the land at the first arrival were so delighted, that they wore it in their hats in token of honor. [Back to text]

And who be stars but Warwick's bearded staves?

The ragged or bearded staff was a part of the arms belonging to the earldom of Warwick. [Back to text]

Sland'ring Duke Reignier with base beggary.

Reignier, Duke of Anjou, called himself King of Naples, Sicile, and Jerusalem, having neither inheritance nor tribute from those parts, and was not able, at the marriage of the Queen, of his own charges to send her into England though he gave no dower with her, which by the Duchess of Gloucester was often in disgrace cast in her teeth. [Back to text]

A Kentish rebel, a base upstart groom.

This was Jack Cade, which caused the Kentishmen to rebel in the twenty-eighth year of Henry the Sixth. [Back to text]

And this is he the white rose must prefer

By Clarence' daughter matched to Mortimer.

This Jack Cade, instructed by the Duke of York, pretended to be descended from Mortimer which married Lady Philip, daughter to the Duke of Clarence. [Back to text]

And makes us weak by strength'ning Ireland.

The Duke of York, being made deputy of Ireland, first there began to practice his long-intended purpose, strengthening himself by all means possible that he might at his return into England by open war claim that which so long he had privily gone about to obtain. [Back to text]

Great Winchester untimely is deceased.

Henry Beaufort, Bishop and Cardinal of Winchester, son to John of Gaunt begot in his age, was a proud and ambitious prelate, favoring mightily the Queen and the Duke of Suffolk, continually heaping up innumerable treasure, in hope to have been Pope, as himself on his deathbed confessed. [Back to text]

With France t'upbraid the valiant Somerset.

Edmund Duke of Somerset, in the twenty-fourth of Henry the Sixth, was made Regent of France, and sent into Normandy to defend the English territories against the French invasions, but in short time he lost all that King Henry the Fifth won, for which cause the nobles and the commons ever after hated him. [Back to text]

T'endure these storms with woeful Buckingham.

Humphrey, Duke of Buckingham, was a great favorite of the Queen's faction, in the time of Henry the Sixth. [Back to text]

And one foretold by water thou should'st die.

The Witch of Eye received answer by her spirit that the Duke of Suffolk should take heed of water; which the Queen forewarns him of, as remembering the witch's prophecy, which afterward came to pass. [According to tradition, the pirate who killed Suffolk was named Walter, which -- as the poetry of Sir Walter Ralegh indicates -- was often pronounced in the past without an audible L. Shakespeare gives him the surname of Whitmore -- ed.] [Back to text]

Also, this installment comes with a bonus illustration!

"And, telling Henry of thy beauty's story,

I taught myself a lover's oratory

...Nor left him not, till he for love was sick,

Beholding thee in my sweet rhetoric."

That was fun. I may have to go back and do them for other epistles. ;)

NEXT TIME: Edward IV is a mack daddy. This makes him unworthy of footnotes, but Jane Shore is impressed. But she's only going to put out because he's the King, you know.

1. The only other significant couple from this general period in English history I can think of who has a Notable Pirate Encounter are Henry IV and Joan of Navarre, and we're already past them, besides which they're never in stuff like this anyway. Here's the real thing instead. No pirates, though.