Cinema Studies Blog/Essay Submission

Sizing Up Film and Television through Heroes and Firefly

Through close analysis of two contemporary television shows discuss how (and why)

the boundaries between television and film are breaking down.

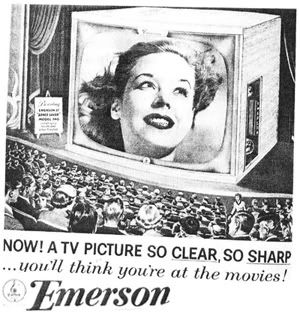

In 1952 Emerson Electric Company advertised their new television with the caption “Now! A TV pictures so clear, so sharp… you’ll think you’re at the movies!” (Spigel 1992:104).

Television, it seems, has been striving to reach the standard set by cinema from an early age. Seemingly, it has the advantage, being a near-constant, twenty-four hour installation in most Western homes, and has a lot more time and opportunity to influence its viewers. But by the same token, film is an ‘event’, a once-off opportunity to blast us with as much entertainment and viewing pleasure as possible. Preference is, of course, up to the individual, but the question we now ask is whether, in chasing each other through the competitive field of contemporary media, film and television have become no longer two separate institutions, but merely two different ways of observing the same entity.

We begin by observing the structure of the film verses that of television. On average, a contemporary mainstream Hollywood film such as Horton Hears a Who! (2008, 88 minutes) 21 (2008, 123 minutes), or Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian (2008, 145 minutes) will last from about an hour and a half to two hours or more, compared to an episode of a television serial, without ad breaks, which tends to run between 30 minutes and an hour. Usually only specials and telemovies last longer, and this hasn’t changed much since the early years of television (episodes of The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin (1954-1959) for example, ran for 30 minutes). From this sort of evidence, Rod Stoneman gleans: ‘the aspiration to longevity seems to be confined to cinema rather than television culture… Perhaps it is linked to the shorter attention span of television production in general - aesthetically weaker material, shorter-term aspirations for each individual piece’ (Stoneman 1996:121). This is a strong statement that really concerns only individual episodes. Were Stoneman to consider the overall longevity of a television show, with 6 to 24 episodes a series, he might not have made this claim. Buffy the Vampire Slayer, for example, ran for seven seasons and aired 144 episodes. With an average running time of 43 minutes, that’s 103 hours of material. If anything, the serial is the ultimate ‘aspiration to longevity’, in that it aspires to tell a story that spans weeks or months if not years.

As Angela Ndalianis contends in her article, ‘Television and the Neo-Baroque’, the ‘infinite work in progress’, is becoming more favoured than ‘closed narrative forms’ (Ndalianis 2005:86), and this is not only true of television. To name a select few of the films that utilise serial form: Star Wars, which had six ‘episodes’ over two trilogies between 1977-2005, Pirates of the Caribbean, which shot its second and third instalment at the same time and released them less than a year apart, The Lord of the Rings,, also shot concurrently, The Matrix, Indiana Jones, Aliens, American Pie, and Die Hard, not to mention all the recently-released sequels to Disney classics such as Aladdin, The Little Mermaid, The Lion King, and Bambi1. These latter sequels, in some cases released up to 60 years after the original, are examples of a more ‘closed’ serial form than Pirates of the Caribbean II and III, but have nevertheless been made to satisfy the viewers’ growing need for continuation.

Open serial vs. closed serial - The Pirates of the Caribbean II (2006) and III (2007),

Bambi (1945) and Bambi II (2005).

Not only that, but films that cannot benefit enough from film sequels turn to television serial form. Buffy was originally a film, and Star Wars, Superman, Aladdin, The Little Mermaid and Jumanji all have television counterparts - again, just to name a few. The ‘serial’ nature of television, then, is being carried over into the film world, and indeed vice versa, with television series like The Simpsons, Mr. Bean and Firefly being made into films.

Moving on, one of the factors that need to be considered in the digital age is that of technology. Particularly now in the case of animated features like Shrek and Horton Hears a Who!, new films have to be more technologically advanced than previous ones to be respected. This is also true of non-animation films requiring lots of special effects and CGI, like the Pirates of the Caribbean films and, more recently, Speed Racer. Once upon a time, Cinema used such different technology to television that it caused problems when reformatting films for distribution on TV (McLoone 1996:86), but today, such interaction is easier and is becoming more and more so as ‘digital cinematography’ becomes a more common decision with contemporary filmmakers (Kirsner 2006). Since director George Lucas kicked off the trend in 2002 with Star Wars: Episode II - Attack of the Clones, films like Open Water (2003), Click (2006), Superman Returns (2006) and Speed Racer (2008) have been shot digitally instead of on the traditional celluloid. Scott Kirsner, in his article on the subject, contends that although there are advantages and disadvantages to both mediums, we are at the beginning of a transition that will mean film is no longer the ‘default decision’ (Kirsner 2006). If this is the case, no longer can it be argued that all television is digital, and all cinema is film.

John Ellis, in his article ‘Speed, Film and Television: Media Moving Apart’ explains that film distinguishes itself from television by its use of new digital image technology. He claims that ‘cinema uses the new potential to make ever more realistic, yet impossible, images’, and then goes on to describe in great detail the way magazine and news programs on television use such technologies to ‘make constantly changing collages of images’ instead. This, according to Ellis in 1996, meant the divergence of cinema and television. Ten years later, Tim Kring and NBC gave us Heroes.

Heroes uses digital technology for a lot more than an attractive weather forecast. Although by no means the first use of special effects by a television drama, it is perhaps the most integrated use of them that we have seen so far. Star Trek, Smallville, Supernatural, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and other science fiction serials that require CGI, for the most part indicate a supernatural or extra-terrestrial ‘reason’ for these impossible images - Heroes, on the other hand, works on the premise that the characters’ abilities are the result of evolution, a natural progression of the species. The special effects on the show are therefore geared towards making spontaneous regeneration, human flight or mind-reading look scientifically viable so that it is accepted by the audience. In other words, it is a different experience from seeing spaceships in Firefly, or Superman using his heat-vision, and thinking ‘that’s a special effect’.

Meredith Gordon, Pyrokinetic - Heroes makes amazing powers look achievable on screen.

Heroes shows us that in this age, television makes just as much use of ‘new technology’ as a visual aesthetic as cinema does. Zoic, the special effects provider for features such as Spiderman 2, Serenity and Day After Tomorrow, also work for television programmes like 24, Rome and Cold Case (Zoic Studios 2008). The MASSiVE software used to create large numbers of figures in Lord of the Rings and Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End has been used not only to create crowds of creatures in Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Doctor Who, but has also been used in high-profile TV-ads like ‘The Big Ad’ for Carlton Draught (Massive Software: 2007).

The Carlton Draught Big Ad from 2005, using Massive Software

to create multiple figures with CGI technology (click to watch).

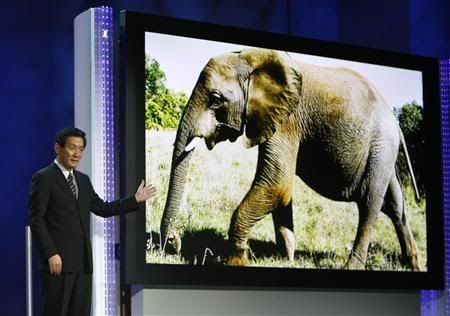

Then there is the technology used to exhibit our entertainment. It might still be fair to say that the cinema itself is a much ‘bigger’ experience than television. The biggest cinema screen in the world is 30.6m wide (Scoop 2007), compared to the largest TV made so far, which is 3.81m (Reuters 2008). In Stoneman’s words, ‘cinema’s project is in a larger scale, wider image of the world’ (1996:121).

Television, however, will not settle for second best. Advances are being made all the time to increase the viewing pleasure of home entertainment. In fact, what used to be called ‘home theatre’ is now more commonly known as ‘home cinema’. Perhaps the most defining aspect of these new technologies is that, far apart from watching a reformatted film DVD on a High Definition TV screen with 5.1 Surround Sound, broadcasting channels now exist that beam the higher quality images and audio into our homes. Australian networks Ten and Seven both recently introduced free-to-air HD channels, both with 5.1 Dolby surround, and Ten transmits in 1080i, the highest definition for television screens that exists so far (Network Ten 2007). Perhaps the literal size of the home cinema will not increase any further, because the advantage of television is that it is much more accessible and consistently available than film. In any case, the size of the ‘experience’ of television, while stile a notable barrier between TV and film, continues to grow.

Matsushita released this 3.81m (150 inch) screen in January 2008

Cinema has yet to be live. While there is an established element of television that is live, like the news, sport, some chat or panel shows, and even some special episodes of serials like The Vicar of Dibley, Blue Heelers and Will and Grace, film is a recorded medium. Conrad Schoeffter takes this distinction a step further by insisting that film ‘is fiction… television on the other hand, is reality based, not just where news and documentaries are concerned…. Most television movies are rooted in fact. Talk shows are perceived as real. In game shows, real people truly win or lose. By extension, we take a lot of things we see on television at face value’ - (Schoeffter 1998:113)

Schoeffter has either fallen into a mass generalisation, or his article just has not withstood the test of time. That ‘television movies are rooted in fact’ might be true of one that is rooted in fact, like The Ron Clark Story (2006), but what of a more recent example, The Colour of Magic (2008) based on the fantasy book by Terry Pratchett?

Fact vs. Fiction: The Ron Clark Story (2001) and The Colour of Magic (2008)

Let us take Firefly, for example. Classified as a ‘space western’ (Richardson 2007:140), the show is set in 2517 and examines entirely fictional events that take place after the humans have emigrated from earth. The characters live in a spaceship and fly between other ‘terraformed’ planets where live the civilian populations. The film Serenity, released after the show’s short-lived run on air, is just as fictional as the television series and vice versa. As Serenity is essentially a continuation of the serial in film-form, it is useful to examine both in order to note the ‘barriers’ between a TV show and a film of the same concept. For example, Serenity shows us that the depth and intricacies of details one can get from a TV show in its entirety are much harder to achieve with film. The film does not, for example, make clear that the character of Inara is a ‘companion’ (licensed prostitute), no doubt because of time constraints, even though this is an integral element of the TV series. It also demonstrates how film needs to be much more immediate than television. Firefly spent all its fourteen episodes slowly building up clues as to the mysteries behind the character of River. Serenity, as a film, has no such luxury, as film viewers expect to be imbued with all the relevant facts by the film’s end. In Serenity we find out that River is an assassin and psychic brainwashed by the alliance to be a powerful weapon. We also discover the origins of the terrifying creatures known as ‘Reavers’, which, in Firefly, were barely even shown on screen due to the need to make them as mysteriously ominous as possible over the course of the show. River also defeats the Reavers in Serenity, a conclusion-like device that, it is fair to say, would not have been used for a long time on Firefly as it would have diminished their considerable menace and decreased options for future episodes.

Heroes does not have a film counterpart, but in many ways Heroes is a more ‘film-like’ show than Firefly. Cast and crew have likened working on the show to making a ‘mini-movie’ each week (NBC 2007). In the DVD commentary for the episode ‘Company Man’, Director Allan Arkush and Writer/Executive Producer Bryan Fuller cite no less than five films to be their influences for this episode: Dog Day Afternoon, Raw Deal, Out of the Past, Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Mind and Constant Gardener (for its modern editing style). This episode seems to be a particularly ‘film-like’ one, as it centers around one thread of the story instead of three or four, as is the Heroes norm. Jack Coleman, who plays Noah Bennett on the show, says that each episode ‘feels like a 50-minute feature to me, because it has a beginning, midde and an end in a way that most, especially serialised television [does not]’ (Heroes: Season 1 DVD 2007). The commentary on other episodes also mentions that Heroes has two simultaneous units working on each episode at any time, and that there are at least 250 crew for each episode - closer to that of a film than an average television serial (ibid).

It must also be noted that television, and certainly in the case of shows like Heroes and Firefly, television is a much more ‘visual experience’ than it was at the time of Schoeffter’s article. According to him in 1998: ‘[cinema] is a visual experience… The content of a television movie you can get with your eyes closed. Television is an oral medium, to the point where people get uncomfortable when their little box does not talk to them’ (1998:114). But in what context can Heroes be classified as an oral medium? It might be true, as Schoeffter claims, that there is more ‘talking’ on TV, though it would be hard to prove as such without counting the average number of words for each, and of course it would depend on the type of programming under scrutiny - A Current Affair, for example, is bound to be a bit wordy compared to a film like The Orphanage. But in the case of shows like Firefly and Heroes, it must be argued that the experience is extremely visual.

In episode ‘The Message’ (Firefly 2003), the pilot employs some fantastic-looking

flying techniques, as do the special-effects team with their hand-held camera aesthetic.

Ultimately, it must be conceded that film and television are much closer institutions than they were at their conception, and may well continue to merge, interchange and grow closer in the future. Admittedly there remain some ‘barriers - the ‘live’ element of television, for example, and those features previously discussed in the comparison between Firefly and Serenity. These things, however, such as the need for film to ‘explain’ for the audience’s benefit whereas a television show can hold on the suspense over several episodes or even seasons, are not necessarily ‘barriers’. More, they are distinguishing factors that give us more choice in our viewing opportunities. Television and film are separate institutions, and will in all likelihood remain so, but in the words of Michael Eaton: ‘‘films would not be made were it not for the investment of television. Television would not have been so consistently good were it not for the aspiration to be more like film’ (1998:142).

1Full list of films and their sequels in Filmography below.

----||||----

Bibliography

Abbott, Stacey, ed., 2005, Reading Angel, I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, London

Calabrese, Omar, 1992, ‘Rhythm and Repetition’ in Neo-Baroque: A Sign of the Times, 27-46. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Eaton, Michael, 1998, ‘Cinema and Television: From Eden to the Land of Nod?’ in Cinema Futures: Cain, Abel or Cable?: The Screen Arts in the Digital Age, eds. T. Elsaesser and K. Hoffmann, 137-142, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam

Ellis, John, 1996, ‘Speed, Film and Television: Media Moving Apart’ in Big Picture, Small Screen: The relations between film and television, ed. J. Hill and M. McLoone, 107-117, University of Luton Press, UK.

Elsaesser, Thomas and Hoffmann, Kay, eds. 1998, Cinema Futures: Cain, Abel or Cable?: The Screen Arts in the Digital Age, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam

Espenson, Jane, ed., 2004, Finding Serenity, Benbella Books, Dallas, Texas

Hill, John and McLoone, Martin, eds. 1996. Big Picture, Small Screen: The relations between film and television, University of Luton Press, UK.

Klinger, Barbara, 2006, Beyond the Multiplex: Cinema, New Technologies and the Home, University of California Press, California

Marill, Alvin. H., 1987, Movies Made for Television: The Telefeature and the Miniseries 1964-1986, New York Zoetrope, New York

McLoone, Martin, 1996, ‘Boxed In?: The Aesthetics of Film and Television’ in Big Picture, Small Screen: The relations between film and television, ed. J. Hill and M. McLoone, 76-95, University of Luton Press, UK.

Richardson, J. Michael and Rab, J. Douglas, 2007, ‘The Existential Joss Whedon: Evil And Human Freedom in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly And Serenity’, McFarland & Company Inc., USA

Schoeffter, Conrad, 1998, ‘Scanning the Horizon: A Film is a Film is a Film’ in Cinema Futures: Cain, Abel or Cable?: The Screen Arts in the Digital Age, eds. T. Elsaesser and K. Hoffmann, 137-142, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam

Sorlin, Pierre, 1998, ‘Television and the Close-up: Interference or Correspondence?’ in Cinema Futures: Cain, Abel or Cable?: The Screen Arts in the Digital Age, eds. T. Elsaesser and K. Hoffmann, 137-142, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam

Spigel, Lynn, 1992, Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America, University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Stoneman, Rod, 1996, ‘Nine Notes on Cinema and Television’ in Big Picture, Small Screen: The relations between film and television, ed. J. Hill and M. McLoone, 118-132, University of Luton Press, UK.

Articles

Kirsner, Scott, 2006, ‘Digital Cinematography: The Big Pixel’, The Hollywood Reporter (June)

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/hr/search/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1002688109

Reuters.com, 2008, ‘Matsushita unveils world’s biggest TV’, Thomson Reuters (January)

http://www.reuters.com/article/technologyNews/idUSN0740737820080107

Scoop Culture, 2007, ‘NZ Houses Biggest Cinema Screen In The World’, Scoop Culture (March)

http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/CU0703/S00302.htm

Filmography

Aladdin, Ron Clements and John Musker, 1992

Aladdin: Return of Jafar, Tad Stones, 1994,

Aladdin and the King of Thieves, Tad Stones, 1996

Alien, Ridley Scott, 1979

Aliens, James Cameron, 1986

Alien 3, David Fincher, 1992

Alien Resurrection, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 1997

Alien vs Predator, Paul W.S Anderson, 2004

Alien vs Predator: Requiem, Colin Strause and Greg Strause, 2007

American Pie, Chris Weitz and Paul Weitz, 1999

American Pie 2, James B Rodgers, 2001

American Wedding, Jesse Dylan, 2003

American Pie Presents:Band Camp, Steve Rash, 2005

American Pie Presents: The Naked Mile, Joe Nussbaum, 2006

Bambi, David D. Hand, 1942

Bambi II, Brian Pimental, 2006

Bean, Mel Smith, 1997

Bean 2: Mr Bean’s Holiday, Steve Bendelack, 2007

Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian, Andrew Adamson, 2008

Click, Frank Coraci, 2006

The Colour of Magic, Vadim Jean, 2008

Constant Gardener, Fernando Meirelles, 2005

Day After Tomorrow, Roland Emmerich, 2004

Die Hard, John McTiernan, 1988

Die Hard 2, Renny Harlin, 1990

Die Hard With a Vengeance, John McTiernan, 1995

Die Hard 4: Live Free or Die Hard, Len Wiseman, 2007

Dog Day Afternoon, Sidney Lumet, 1975

Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Mind, Michel Gondry, 2004

Horton Hears a Who!, Jimmy Hayward, 2008

Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark, Steven Spielberg, 1981

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Steven Spielberg, 1984

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Steven Spielberg, 1989

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Steven Spielberg, 2008

Jumanji, Joe Johnston, 1995

The Lion King, Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff, 1994

The Lion King 2: Simba’s Pride, Darrell Rooney, 1998

The Lion King 1 ½,, Bradley Raymond, 2004

The Little Mermaid, Ron Clements and John Musker, 1989

The Little Mermaid: Return to the Sea, Jim Kammerud and Brian Smith, 2000

The Little Mermaid: Ariel’s Beginning, Peggy Holmes, 2008

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, Peter Jackson, 2001

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, Peter Jackson, 2002

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Peter Jackson, 2003

The Matrix, The Wachowski Brothers, 1999

The Matrix Reloaded, The Wachowski Brothers, 2003

The Matrix Revolutions, The Wachowski Brothers, 2003

Open Water, Chris Kentis, 2003

The Orphanage, Juan Antonio Bayona, 2007

Out of the Past, Jacques Tourneur, 1947

Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl, Gore Verbinski, 2003,

Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, Gore Verbinski, 2006

Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End, Gore Verbinski, 2007

Raw Deal, John Irvin, 1986

Serenity, Joss Whedon 2005

The Simpsons Movie, David Silverman, 2007

Shrek, Andrew Adamson, 2001

Shrek 2, Andrew Adamson, 2004

Shrek the Third, Chris Miller, 2007

Speed Racer, The Wachowski Brothers, 2008

Spiderman 2, Sam Raimi, 2004

Star Wars: Episodes I-VI, George Lucas, 1977, 1980, 1983, 1999, 2002, 2005

Superman, Richard Donner, 1978

Superman Returns, Bryan Singer, 2006

Television

24, 2001, Created by Joel Surnow and Robert Cochran, FOX

A Current Affair, 1988-, Nine Network

The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin, 1954-1959, ABC

Aladdin, 1994-1996, Walt Disney Television, CBS

Blue Heelers, 1994-2006, Created by Tony Morphett and Hal McElroy, Seven Network

Buffy the Vampire Slayer, 1997-2003, Created by Joss Whedon, UPN/WB

Cold Case, 2003-, Created by Meredith Stiehm, CBS

Doctor Who (current series), 2005-, Created by Sydney Newman, BBC1

Firefly, 2002-2003, Created by Joss Whedon, FOX

‘The Message’, Firefly, 1.12, Dir. Tim Minear, FOX 2003

Heroes, 2006-, Created by Tim Kring, NBC

Heroes: Season 1, DVD. Universal Studios 2006/07 [DVD Commentary]

‘Distractions’, Heroes, 1.14, Dir. Jeannot Szwarc, NBC 2007

‘Company Man’, Heroes 1.17, Dir. Allan Arkush, NBC 2007

Jumanji, 1996-1999, Created by Arlene Klasky, UPN Kids

The Little Mermaid, 1992-1994, Walt Disney Television, CBS

Mr Bean, 1990-1995, Created by Rowan Atkinson and Richard Curtis, ITV

Rome, 2005-2007, Created by John Milius, William J. MacDonald and Bruno Heller, BBC

The Simpsons 1989-, Created by Matt Groening, FOX

Smallville, 2001-, Developed by Alfred Gough and Miles Millar, WB/CW

Star Trek, 1966-, Created by Gene Roddenberry, NBC/UPN

Star Wars: Clone Wars, 2003-2005, Lucasfilm Animation, Cartoon Network

Supernatural, 2005, Created by Eric Kripke, WB/CW

The Vicar of Dibley, 1994-2007, Created by Richard Curtis and Paul Mayhew-Archer, BBC

Will and Grace, 1998-2006, Created by David Kohan and Max Mutchnick, NBC

Websites

Massive Software, 2007, www.massivesoftware.com

Zoic Studios, 2008, www.zoicstudios.com

NBC Website, 2008, www.nbc.com

Network Ten Corporate, http://www.tencorporate.com.au/

Images and Video

Emerson Electric Advertising

Spigel, Lynn, 1992, Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America, 104

Bambi

http://www.animatedheroes.com/bambi.html

Bambi II

http://www.filmjunk.com/2006/01/26/preview-11-minutes-of-bambi-2-online/

Pirates II

http://www.cinema.com/film/9311/pirates-of-the-caribbean-dead-mans-chest/gallery/page_50.phtml

Pirates III

http://www.indielondon.co.uk/gallery/pirates-of-the-caribbean-at-worlds-end-gallery-2

Meredith Gordon, Heroes episode ‘Distractions’

http://www.stripedwall.com

The Carlton Draught ‘Big Ad’

http://download.massivesoftware.com/client_work/cubbigad.lo.mov

Matsushita 150 inch TV

http://www.reuters.com/article/technologyNews/idUSN0740737820080107

The Ron Clark Story (clip)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z-OwqrcUlGM

The Colour of Magic (trailer)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6dm2uT5GDcg

‘The Message’ (clip)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C7rmUDvN4fw