Melvin Sokolsky: Seeing Fashion

The period between 1955 and 1970 has become widely recognized as a kind of golden age in American magazine culture. In these years the commercial imperative had failed to over-ride the arguably irrational urge to utilize mass-circulation periodicals as a platform for personal expression. Following a time of neglect or indifference, the legacy of many photographers, artists, and designers is again investigated and celebrated. One of the more unusual figures in this pantheon was Melvin Sokolsky. His relatively brief but intense career as a photographer was simultaneously paradigmatic and evidence of how an individual signature could prevail in a commercial environment.

Bubble On the Siene, Paris 1963

Bubble, NewYork 1960

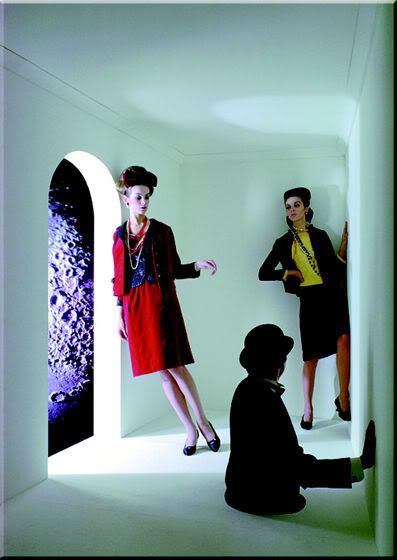

Surreal Moon

Lip Streaks, 1965

Lena Horne Show Cover, 1963

Melvin Sokolsky’s Affinities

By Martin Harrison

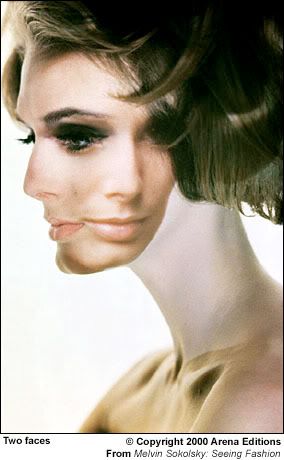

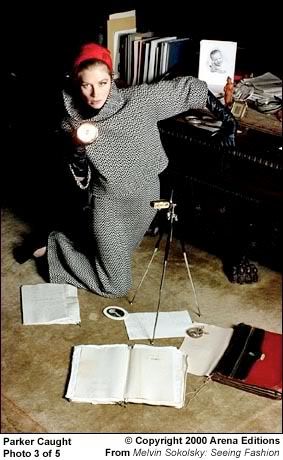

"Astonishingly inventive" and "technically consummate" are typical of the encomiums that Sokolsky’s photographs elicit. The constant stream of frequently audacious ideas that he brought, month after month, to the pages of Harper’s Bazaar certainly bears witness to the claims of fecundity. And the effects he achieved, apparently effortlessly, were the result of tireless experimentation and skillful craftsmanship. He stretched beyond the nominal brief of illustrating clothes, urged on by his tenacious imagination, fired up by an almost child-like thrill with the power of the image, with articulating the body-in-space, and the search to find new ways to make an impact on the magazine page.

With no formal training, Sokolsky had to rely on instinct and careful observation for his professional photographic education. He had begun to photograph at the age of ten, using his father’s box camera. His father kept a family album that included old photographs of himself at the ages of five, ten, and fifteen; for Melvin it was disturbing, because each print had a different palette: "I could never make my photographs of Butch the dog look like the pearly finish of my father’s prints, and it was then that I realized the importance of the emulsion of the day." To be a photographer he knew he would have to grasp not only camera techniques but also the refinements of texture and finish, as well as spatial concepts.

About 1954, at an East Side barbell club, he met Bob Denning, who was assistant to an established advertising photographer, Edgar de Evia: "I discovered that Edgar was paid $4000 for a Jell-O ad, and the idea of escaping from my tenement dwelling became an incredible dream and inspiration." Technical information avidly gleaned from the Conde Nast book, The Art and Technique of Color Photography, was augmented by de Evia’s answers to the "thousands of questions" Sokolsky posed. Eventually "Edgar either got bored, or I asked too many questions," and these visits constituted the sum of Sokolsky’s technical teaching. Unsurprisingly, his first attempts at photography used a lot of diffusion, in imitation of the Tissot-like effects favored by de Evia. The photographer Ira Mazer passed on a small assignment, and Sokolsky began in this way, gradually building up a portfolio by making the best out of routine advertising assignments. It was about this time, while visiting William Helburn’s studio, that he met a model named Button, his future wife and a central figure in his life and career. Thereafter, his progress was swift.

If Sokolsky’s drive and energy supplied the chutzpah to launch his assault across the Bazaar’s Madison Avenue threshold, he needed something more tangible if he was to hold down the job. The core of what he had to offer was innate. It was, apparently, already evident in his behaviour as a child, when he disturbed adults with his habit of holding both hands up to his face, thumbs at right angles, framing the scenes he witnessed like a budding film director: "They became so alarmed as I lined up people at the table, that they eventually took me to an optician, figuring there was a problem with my eyesight." The desire to come to terms with reality by transforming it into images, and the fascination with placing people in spatial relationships, were to pay off later. The precocious sensitivity to lighting and environmental ambience has stayed with him to the extent that (almost, one senses, with embarrassment) he recognizes that he is profoundly distracted in a meeting if the people in a room are arranged and lit in a disconcerting manner.

When Sokolsky began to contribute to Harper’s Bazaar in 1959, the magazine had recently dispensed with the services of Alexey Brodovitch, the Russian art director who had been its guiding visual force since 1934 and guru to many of America’s leading photographers. As the Fifties wore on, Brodovitch-formerly the insatiable promoter of the new-was riding on his reputation; though never less than elegant in its presentation, the magazine appeared to run out of fresh ideas. The Hearst organization looked enviously at Esquire, where a young art director, Henry Wolf, was a key member of a team that was producing a lively magazine that offered a more contemporary insight and Wolf’s innovative layout and typography to match.

A high fashion glossy was evidently not the same as a men’s general interest title, but Wolf was soon poached by the Bazaar. He was new and determined to make changes. Of the established photographers, some, like Richard Avedon and Lillian Bassman, were unassailable, but Wolf was aiming to introduce more variety. He began to sign up photographers with distinctive new visions, from the oblique lyricism of Saul Leiter to the eye-catching devilment of Melvin Sokolsky.

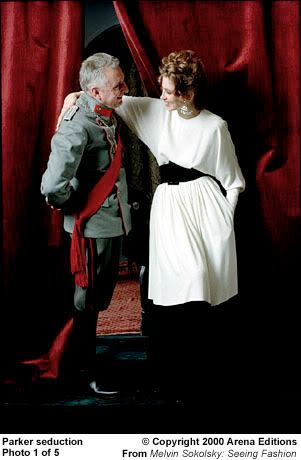

Sokolsky’s interests devolved, like most great fashion photographers, on the woman in front of the camera, rather than the illustration of garments. From childhood, the contact with great paintings in the museums and galleries of New York was a seminal influence: besides his abiding love of Surrealism, there were less usual inspirations, such as the interior spatial effects of Velasquez, and of the Flemish masters Van Eyck and Van der Weyden, and the disturbing subject matter of Bosch and Brueghel. Velasquez’s device of including his self-portrait in the open doorway in the background of "Las Meninas" would eventually recur in a series of Sokolsky’s fashion photographs: by photographing into a mirror, the photographer substituted himself for the painter, the enigmatic presence and hint at voyeurism intensified by the pared-down compositional elements .

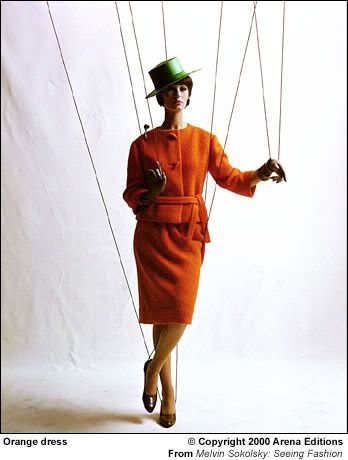

For all Sokolsky’s ingenuity, the fundamentals that drove his work and inspired its endless variety were his fascination with female form and gesture, and he cites specifically the paintings of Balthus as having led him to understand that this was his metier . He says that in every fashion photograph "I tried to show the gesture of the unclothed body beneath the garment: I wanted it to be as if the clothes did not exist. For me, if the merchandise is more important than the woman, then it’s not a good photograph. The only times that the clothes ever interested me were when they suited the woman wearing them: ideally, nothing should look store-bought."

In the delicately-poised tussle for supremacy encountered in the business of producing a fashion magazine, Sokolsky generally found it difficult to convey his somewhat alternative agenda to the fashion editors. They in their turn had ambitions to teach this young Vulgarian (an epithet photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe attached to him early on) all about fashion: "But what they didn’t realize was that Chanel, for example, ultimately loved women, and that in her designs she tried to make new clothes appear worn-in." In analysing and experimenting with gesture, Sokolsky instructed models to turn the palms of their hands towards the lens-a deliberate flouting of the prevailing Renaissance norms of elegance. It is clear from his early magazine work that he was rebelling against what he saw as fashion’s over-riding tendency to follow a trend: "I was instinctual in my approach, and all I had to offer at first was irreverence."

When Sokolsky began to contribute to Harper’s Bazaar in 1959, the magazine had recently dispensed with the services of Alexey Brodovitch, the Russian art director who had been its guiding visual force since 1934 and guru to many of America’s leading photographers. As the Fifties wore on, Brodovitch-formerly the insatiable promoter of the new-was riding on his reputation; though never less than elegant in its presentation, the magazine appeared to run out of fresh ideas. The Hearst organization looked enviously at Esquire, where a young art director, Henry Wolf, was a key member of a team that was producing a lively magazine that offered a more contemporary insight and Wolf’s innovative layout and typography to match.

A high fashion glossy was evidently not the same as a men’s general interest title, but Wolf was soon poached by the Bazaar. He was new and determined to make changes. Of the established photographers, some, like Richard Avedon and Lillian Bassman, were unassailable, but Wolf was aiming to introduce more variety. He began to sign up photographers with distinctive new visions, from the oblique lyricism of Saul Leiter to the eye-catching devilment of Melvin Sokolsky.

Sokolsky’s interests devolved, like most great fashion photographers, on the woman in front of the camera, rather than the illustration of garments. From childhood, the contact with great paintings in the museums and galleries of New York was a seminal influence: besides his abiding love of Surrealism, there were less usual inspirations, such as the interior spatial effects of Velasquez, and of the Flemish masters Van Eyck and Van der Weyden, and the disturbing subject matter of Bosch and Brueghel. Velasquez’s device of including his self-portrait in the open doorway in the background of "Las Meninas" would eventually recur in a series of Sokolsky’s fashion photographs: by photographing into a mirror, the photographer substituted himself for the painter, the enigmatic presence and hint at voyeurism intensified by the pared-down compositional elements .

For all Sokolsky’s ingenuity, the fundamentals that drove his work and inspired its endless variety were his fascination with female form and gesture, and he cites specifically the paintings of Balthus as having led him to understand that this was his metier . He says that in every fashion photograph "I tried to show the gesture of the unclothed body beneath the garment: I wanted it to be as if the clothes did not exist. For me, if the merchandise is more important than the woman, then it’s not a good photograph. The only times that the clothes ever interested me were when they suited the woman wearing them: ideally, nothing should look store-bought."

In the delicately-poised tussle for supremacy encountered in the business of producing a fashion magazine, Sokolsky generally found it difficult to convey his somewhat alternative agenda to the fashion editors. They in their turn had ambitions to teach this young Vulgarian (an epithet photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe attached to him early on) all about fashion: "But what they didn’t realize was that Chanel, for example, ultimately loved women, and that in her designs she tried to make new clothes appear worn-in." In analysing and experimenting with gesture, Sokolsky instructed models to turn the palms of their hands towards the lens-a deliberate flouting of the prevailing Renaissance norms of elegance. It is clear from his early magazine work that he was rebelling against what he saw as fashion’s over-riding tendency to follow a trend: "I was instinctual in my approach, and all I had to offer at first was irreverence."

Like many of the talented individuals who operate in a high-powered, creative, but competitive environment, Sokolsky’s relationships with his colleagues at Harper’s Bazaar, were not always smooth. Of the art directors with whom he collaborated, he evidently found it much easier working with Henry Wolf ("He dared you to produce your best, he made you responsible.") than with his successor Marvin Israel ("Henry was the great catalyst, Marvin thought antagonism was a catalyst-he panicked you."). Among the fashion editors with whom he worked, he was personally ambivalent about the great Diana Vreeland, but admired both her sense of humor and the way she fought with the Editor-in-Chief, Nancy White, against compromise and censorship of the photographs: "Vreeland had this annoying posture of superiority, but she was fanatically committed to her work, whereas the best Nancy White could say about a picture was ‘It’s pretty’." He had to fight, too, for the models of his preference. When he discovered Donna Mitchell, for example, it took all of his persuasion to be allowed to take her to Paris, though once the resistance was overcome and the photographs were successful she was in demand from all quarters.

Inevitably, and frustratingly for the photographer, some of his more unconventional ideas failed to reach publication. In retrospect, some of the killed sittings for Bazaar seem like mouth-watering gestures of defiance. Notable among these is the series of leatherwear he photographed on model Simone d’Aillencourt, her elegant hauteur in stark contrast to Sokolsky’s brutally realist location-the Coney Island D-train. He had tried to invoke the atmosphere of a Reginald Marsh painting, but on this occasion Diana Vreeland’s dismissive comment was merely "They are interesting pictures, but I can’t identify with where you have taken them." Even his gently satirical "Fourth of July" cover, in 1960 was deemed too risque for publication, though it was rescued from oblivion six years later to appear on the cover of the prestigious Swiss magazine, Camera.

Of all Sokolsky’s work, the editorial fashion photographs received the broadest public recognition, since they were invariably published together with his by-line. Their extra visibility gives a misleading view of his entire output, for in fact more than three-quarters of his work was in the field of advertising: this is generally published without credits, and consequently the photographer remains anonymous. Though statistically a difficult claim to substantiate, it is likely that Sokolsky was the most successful advertising photographer of the 1960s. Certainly the huge amount of Art Directors Club Awards he received testifies to his high reputation. A major factor in his renown surely stemmed from his philosophy that it was dishonest for a photographer to deliberately turn down a notch, operating on a lower level for advertising assignments: "I resented the attitude that ‘This is editorial and this is advertising’. I always felt, why dilute it? Why not always go for the full shot?"

Before the breakthrough onto Harper’s Bazaar, Sokolsky had spent about eighteen months working mainly on advertising campaigns. His first appearance in the Annual of Advertising and Editorial Art and Design, in 1958, was with a still-life of silverware, a refined and elegantly balanced composition, somewhat in the manner of his distinguished predecessor Leslie Gill; although Sokolsky’s tableau was placed in a Cornell-like box, both his and Gill’s still-lifes entered the lengthier tradition of the nineteenth-century American trompe l’oeil artists such as William Harnett. Reflecting on his career some years ago, Sokolsky told me that the most conducive sittings he undertook were photographing a still-life, a nude, or an untried new face. He was essentially a directorial photographer, and these tabulae rasa, which allowed him the optimum level of responsibility for all of the elements within the picture frame, presented a challenge he relished.

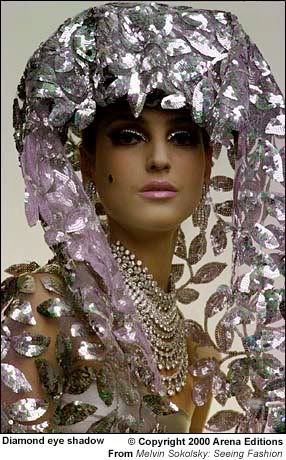

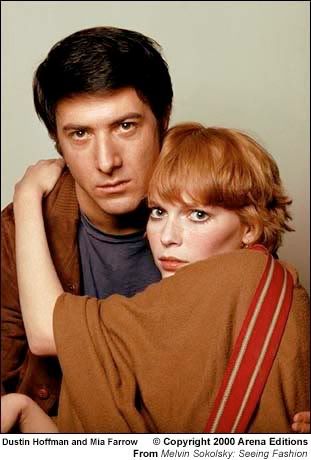

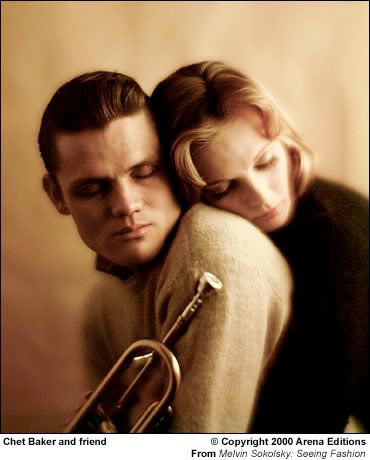

Editorially, Sokolsky was a frequent contributor to many other magazines in addition to Harper’s Bazaar, including McCall’s (for which he photographed a complete one-man issue in October 1962), Ladies Home Journal, Esquire, Show, Newsweek, and the New York Times Magazine. Apart from fashion and still-lifes, he made many distinguished portraits for these magazines, and was frequently commissioned to photograph Hollywood celebrities. He once said that in a fashion image he wanted to photograph the human psyche, an ambition that enabled the transition to photographing an actor or actress to proceed quite smoothly. Some of his most enduring fashion photographs could equally be described as portraits for example, stand comparison with the psychological perception of the portraits of Julie Christie or Mia Farrow.

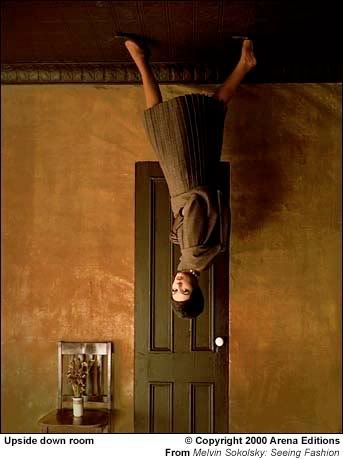

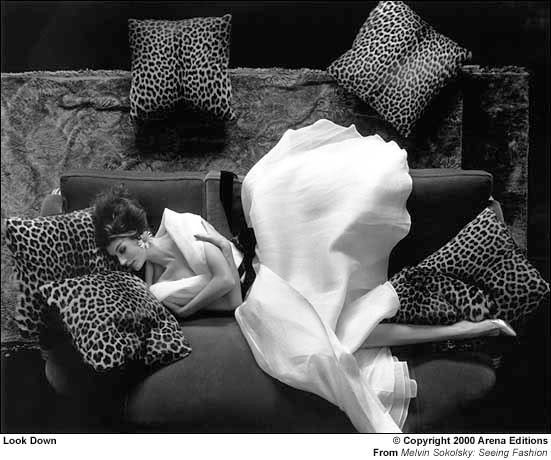

From the outset, Sokolsky’s fashion photography was distinguished by the rapid progression of its themes. Indeed he later believed that the obligation he felt to invent new ideas each month (a pressure that was partly of his own motivation) might have been excessive, and that to have explored certain concepts for longer periods would have been more productive for his own development. For some of the earliest Harper’s Bazaar sittings he eschewed any props beyond an unusually textured backdrop: "I was not interested in a clothes-horse-I was celebrating the beauty of the woman." Shortly afterward he began to explore his atavistic fascination with spatial dislocation in series in which he arranged the model’s limbs to accommodate claustrophobic box-frames , or peered from an elevated viewpoint into a maze-like structure constructed in the studio .

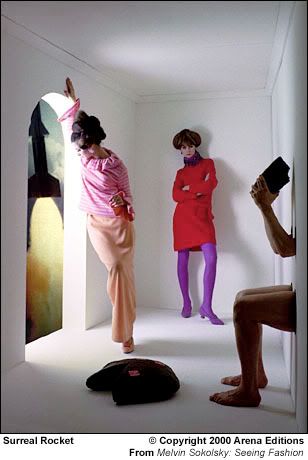

The ideas flowed incessantly. From the genre’s most extreme experiments with scale , through fashion photography’s most overtly surrealist examples (pages 48-51), to highly unconventional multi-figure compositions . Perhaps the most celebrated of all was the acclaimed "Bubble" series for the Spring 1963 Paris Collections (opening pages). These remarkable photographs constitute a kind of finale to the fantasy era of Paris fashion, a warm-humored tribute to inexplicable excess. Salvador Dali, whom he met at this time, became convinced that Sokolsky could actually make him fly. The logical outcome of the epic "Bubble" pictures for Sokolsky was to investigate further the simulation of flight, of weightlessness, which he did in some compelling sequences that continue to influence fashion photographers today .

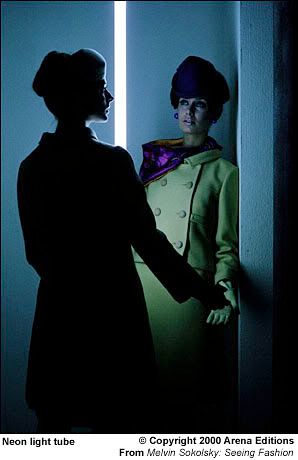

Following these magical performances, Sokolsky felt the only route open to him was a return to simplicity. Photographed on a plain seamless studio backdrop, movement and lighting were the key factors in the appeal of images such as . Sokolsky believed that lighting was an excessive obsession at that time, but, inspired by Josef von Sternberg’s cinema lighting, he achieved some subtle and innovative lighting schemes of his own. In the later 1960s he began to photograph fashion outside the studio environment, a direction that might have been developed further, had his career not taken a different turn. For the New York Times Magazine in 1969, he photographed (on a Polaroid camera) an extended story with three models in which he demonstrated an increasing concern with narrative that presaged his transition from stills to movies. It was a timely story-in one photograph the model smokes a joint-but it would be one of his last important contributions to fashion photography.

After about ten years at the top of his profession, Sokolsky found that art directors began to ask if he was able to translate the look of his stills into film. An experiment with a model in a tub full of bubbles was a great success, and soon he was in great demand: commercials, almost imperceptibly at first, began to dominate his output. He admits to being seduced by the movie camera and the challenge of exploring the grammar of film, and, with his reputation in this field escalating, in 1975 moved his studio to Los Angeles. The change did not signify the end of his involvement in stills, but commissions thinned as he was not only increasingly associated with film, but also removed from the main East Coast locus of assignments. The decade of his most intense involvement with stills was perhaps only a prelude to film, but it can also be viewed as a period of passionate involvement, the cumulative document of a creative spirit in a fascinating period of photographic history.

Sokolsky:

Ideas Trump Technical Advantage

In his rustic hideaway up a steep side of Benedict Canyon, once the home of Lillian Gish, he comes bounding from a sideroom with a sepia toned print of a still life. The digital SLR, a brand new 16 megapixel Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II with a 70-200mm L-Series lens, is still on the tripod and facing the mantelpiece on which the miniatures that made the still life rested. Sokolsky is clearly excited by the image he has just finished retouching and printing. "See the cat's tail?" he says, "I made it in Photoshop." The cat that wasn't ever on the mantelpiece had also been 'shopped' in.

Chicken and egg. Art and craft, artist and technique. Which comes first? For Melvin Sokolsky, a story from his childhood makes it clear. He was nine years old, seated in his family's kitchen.

The happy accident of catching him mid-holiday-card-creating graphically illustrated the point of his subsequent discourse on the idea and its relation to technology and technique. Clearly, the idea of ideas is always bubbling around somewhere in Sokolsky's mind.

That's how, apparently, it started, with an idea. Before he was ever a photographer, he reflects, he was already a photographer. "I started as a photographer when I was 9-10 years old, but it had nothing to do with taking pictures; it was all about the idea, which is to say, composition."

"My mother was cooking at the stove and on the table was a little vase with a flower and a salt and pepper shaker. When she moved I had to adjust my view to make the composition please me. I kept squinting and moving around so much that it turned into a whole megillah ( a Yiddish word that means: rigmarole). My mother thought something was wrong with my eyes and I wound up going to the eye doctor for a bunch of tests; at the end of the day it turned out my eyes were 20-20."

So he started to take pictures in the Lower East Side at now-trendy Ridge and Rivington. Back then it was a rough neighborhood. "I would go to the park for gymnastics and to fly model planes. Then I got into photography just as it was becoming 'hot.' Plus I didn't play ball because I found most team sports too confining vs. gymnastics, where you are on your own."

After school, in those early years, Sokolsky would make prints on a friend's enlarger. He recalls the printmaking among his photography friends as briskly competitive. It proved the best possible learning process and motivator for the young photographer. "It was not about money; just the quality of the product, not the profit," he remembers.

This competitive drive took the form of stubborn, precocious focus that had him dreaming, and scheming in a networking sort of way, to break into fashion photography. It was a golden time, and New York was a magic place for photographers. "It was hot, very popular," he recalls. One of the stars of this creative focal point was Henry Wolf, legendary art director of Harpar's Bazaar. From the rough and tumble tenement life, a teenaged Sokolsky already was being noticed, by Wolf, thanks to an elegant shot Sokolsky took for a fur advertisement published in Harper's Bazaar magazine.

At first Sokolsky thought his big break was a joke. The phone rang in his studio and he answered and thought it was a friend playing a prank, so he hung up. Wolf called again, and told him he wanted to offer him a chance to shoot a Harper's cover.

He didn't get the cover, but did get four pages inside. "You're stronger than I thought you would be, how would you like to become a permanent fixture around here"? Wolf said. And then he offered Sokolsky a dream job, staff photographer at Harper's.

At age 21 he'd arrived. From rebuffs by haughty reps who insisted he would never be among that pantheon of great photographers they represented, Sokolsky was suddenly the object of all their desire. "Agents pursued me after that," he said, "but I never dealt with those who had treated me badly before."

Having caught the wave he rode it boldly; his ideas were distinctive, his photographs always subtly and classically composed. Although he burst on the scene at such a young age, Sokolsky's sensibility has always been refined by his broad knowledge of art, painting and photography, such as this clearly Cubist-influenced photograph shot for Vogue in 2002.

His most famous series of photographs, featuring models posed in a plexiglass, are again in the public eye. The bubble pictures collection is now featured in 'Paris 1963,' opening December 16, 2004 at Los Angeles' Fahey/Klein Gallery.

Sokolsky broadened his work beyond still photography to include shooting commericals and films and has won 25 Clios. Today he continues to shoot for magazines on assignment, most recently for Vibe, Bazaar and Vogue.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Interview

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

BH: How you first became aware of the impact of technology on your photographs, your 'look' or palette?

MS: My father took pictures with a brownie box camera. When I was a teenager, I looked through the album and noticed the quality was different between the old and new prints. He'd used the same drugstore to develop all his film, so I realized that as time passed he'd been using something I call the emulsion of the day from Eastman Kodak. I recognized that this film had an intrinsic quality, so also did the paper used for printing. That was when I recognized that the emulsion of the day decided the destiny of most photographers; not like (Edward) Steichen in his early years when he coated a sheet of glass with emulsion by hand himself. If he did it on a cool day it would be different from if he did it on a warm one. He had no real control any more than you would over how much hair you are going to lose. And his photos from that period, like the flatiron building [ed: link here] are his most interesting versus the later ones at Harper's Bazaar where he used the slick emulsions of the day; basically just buying the same palette as everyone else. His early work was different because the characteristics of the homemade film had the imprint of an individual vision, sometimes quirky because the emulsion dried unevenly or at times reticulated; but the end result was a truly original hand-made image.

BH: What do you think about the state of fashion and commercial photography today as an art form?

MS: I was shooting a commercial with an 11-year-old kid and asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up and he said Donald (Trump). I asked him why. The money, he replied. "But all the money," I asked, "What can you do with it?" "Oh if I had the money I could tell you plenty of things I would do with it," the kid tells me.

Money is important, but I can't imagine it as an end in itself. If Trump did something architecturally interesting in any of his buildings that perhaps I could relate to on some level. But you walk into the lobby of any of his buildings and it's enough to create cavities in your teeth.

I want more than just technical perfection. I want to discover something new each day in my life, something that moves and ignites my interests creatively. With that I wish those embarking on photography to think of ideas being more important than mega pixels or sharpness.

We are living in a strange period of time. We worship technology more than ideas and artistic vision. The tools of technology have become more important than the content of the image.

BH: A technological transition as well as a cultural one?

MS: Throughout history there was always a resistance to change. Many contemporary photographers believe that shooting film is the only true photographic medium. I do not believe there is a universal truth. Does a negative reveal more quality than a transparency? Are the inter-negatives for platinum prints less true or valid than the original negetive? All these questions bring to mind, that throughout art history classic protocol was considered more important than the impact of final image? It is my belief when a photographer makes a decision to release the shutter, the resulting image is only the truth of that specific photographer. Who is the arbiter of what is true or valid? Most of the great artists were rejected when they did not follow the accepted protocol of their time: Van Gogh, Gauguin, Picasso; I could go on and on.

BH: The final effect is not real?

MS: As humans we are all trying to communicate our own a personal vision that we would like share with others. We do not take photographs for decoration purposes only.

In my opinion, the author of 'Photoshop' was the first caveman who tried to alter an image he painted on the cave wall‚ no derogation intended to Mr. Thomas Knoll the author of Photoshop - painting on the cave wall trying to alter his vision in order to please himself and communicate with other cave dwellers. That's basically the way man is wired.

We are at a time where the old guard says digital capture is artificial and unreal looking as compared to film. Nostalgic attraction is an addiction that is a difficult habit to kick. If you examine the most important photo collections of any museum you would find that 90 percent of the pictures on display are not really sharp. I am of the opinion that the only reason to take a sharp picture is because the sharpness enhances the idea and content of that specific image. Nature presents remarkable images that photography can reproduce faithfully; but without personal insight and vision faithfully produced images ring hollow. I believe the axiom of the new technology, if I am interpreting it accurately, is if you have no vision or idea, then sharpness and resolution becomes the idea. Whatever the technical merits of a photographers palette, it is that palette that becomes the individual fingerprint that either touches or repels the viewer.

The digital age has freed me from an interface that in the past has interrupted my rhythm and continuity of thought. When George de la Tour was painting a candlelight scene he worked in a room at his own pace, uninterrupted by the interface of others. It is my belief if a photographers artistic intent is interrupted by social interface, as in a collaboration of minds, or something as simple as waiting for the film to be developed; that gap in continuity and flow compromises the photographers artistic intent. With digital capture, the instantaneous workflow allows you to express and discover from moment to moment the motivation that initiated that particular journey.

BH: How else has digital altered your work?

MS: Digital capture in conjunction with Photoshop has allowed me to create a specific palette for each new idea. That new palette embeds the idea with a look that enhances the spirit of the photograph.

There are many photographers and critics who believe that digital-images are inferior to film-images. The word 'Digital' has become a coded metaphor for 'Bogus Image'. I find the quality of digital-capture in conjunction with PhotoShop gives me more control and refinement in all aspects of image making than I have ever experienced as a photographer.

BH: Digital offers a more refined quality?

MS: Digital capture offers a new set of diagnostic tools that are readily available to professional and amateur photographers. We use light meters to determine the proper exposure of the scene to be photographed. If the film is not up to spec or has not been stored properly you might be in for a not so pleasant surprise; as you would not know the result of the exposure until after the film was developed. Now every kid out of school has a camera and a computer that displays a histogram that instantly evaluates the proper exposure for the image in question. In light of these great tools, I see very few photographers who can create images that in my opinion are worth considering. It is only those Photographers who have ideas and vision that make great pictures. Technical expertise is not the passport to the land of great images; without the idea you have nothing. Photoshop is like a mechanic's toolkit. You can't make a Porsche without plans. You must have the blueprint of an idea to create a work of art.

BH: What concerns have you about the impact of such powerful technology on photography as an art?

MS: My concern is that the attractiveness of photography in conjunction with the tools available to everyone has created a subculture of photographers who are more attracted to the technology than the potential the tools offer them as image makers . The watchword in most of the debates about photography is about resolution and mega-pixels more so than content. We are now able to shoot by candlelight with a handheld camera, which has magnified the landscape of expectation tremendously. Today anyone can shoot quality images by candlelight, but with out any thought about composition or reason, the images other than technical accomplishments are shallow.

BH: As a professional photographer, how has the change to modern digital photography changed the photography business generally?

MS: Digital Photography is changing the landscape of how images are presented to the art director and the public. In the past the photographer shot and developed the picture, edited the chromes on a light table, and then sent them to the art director. The images were then scanned by the prepress team who in most cases interpreted the look of the image. Photographers have always complained about the bad reproduction of their images. Think about it, the fate of an image you may have spent months thinking about or working on is determined by someone you have never met.

The business is changing faster than we can imagine. I think all the great presses, the Heidelbergs, etc. will go by the wayside and the new printing presses will print straight from the disk and yield amazing inkjet quality. Imagine a printing press one block long, like a giant Epson inkjet printer, running at high speed printing the new Vogue magazine in extraordinary ten-color photo quality reproduction.

BH: How did you come to use custom labs, like BowHaus, and master printers?

MS: I was working on my book 'Seeing Fashion' and was complaining to a photographer friend about how very disappointed I was by the scans and LVT's I was getting at a highly recommended lab in town. My friend smiled and said. "If you are looking for a scan that is as good or better than your original negative or chrome see Joe at BowHaus." Joe (Berndt) is possibly the Last of the Mohicans in terms of that personal touch you expect with a laboratory not to mention it is also nice to be working in an atelier atmosphere.

I'm a fairly decent technician but I quickly realized in both conventional and digital photography that for my needs, I was more interested in the final image and less interested in being the world's greatest printer. So I decided to leave my museum quality prints to someone who prints everyday and keeps up with the latest technology. Joe is a problem solver who enjoys the involvement of collaboration. It reminds me of the movie making process, you need people around you who know their craft, and it also saves you time and money; and bottom line your vision becomes a reality.