Happy Bayard Rustin Day

Happy MLK, Jr., Day to all and sundry, where ever you are in the world. I have a warmth for today beyond its literal meaning; it has memories for me. I was part of an organizing coalition trying to mark the day in my college; it was my first real activist success as a student, and those were few and far between in the work I was doing, so it stands out. (It's also a memory of a time when I didn't have a war to organize against. I am young enough that those days are few as well.)

But I was chatting with a friend the other day. She was talking about the speech she gives to her son (who is mixed race and identifiably black, and who she is raising in a very white town) about Martin Luther King, Jr. And her speech is largely about how he was the most palatable of the major leaders of black movements, the one the white mainstream could accept. "And that," she ends the speech, "is why we don't have Malcom X Day, or Bayard Rustin Day."

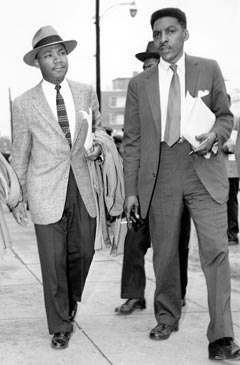

Martin Luther King, Jr., and Bayard Rustin, wearing some snazzy suits.

In honor of her son and mine, I'm making today Bayard Rustin Day.

Bayard Rustin was raised in West Chester, PA, not 20 miles from where my parents live. Like many from Eastern Pennsylvania, he was raised with a Quaker influence. As an adult, he belonged to the same Quarterly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends as I do (though not the same Monthly Meeting). He was a labor leader, a communist, a draft resister. He helped to found the Congress of Racial Equality and the Southern Christian Leadership Council. He studied Gandhian nonviolence and taught its principles to Martin Luther King, Jr., and he organized the March on Washington for Jobs and Equality. He was fired from organizing jobs because he was gay, more than once.

More than any of this, he was a theorist and analyst of the movements he was a part of. He wanted to push all the movements he was involved with towards a broader, integrated goal of liberation from oppression in all its forms: not merely racism, or sexism, or anti-Semitism, or homophobia, but the intergrated system of oppression and suffering rooted in class and identity. This broad progressive agenda was difficult to get mainstream organizations to accept. He didn't care that he would never be the one out front in the crowd. He spoke his truth, and he argued for his cause, and he fought for justice. And that was enough.

I first learned about Rustin from the film Out of the Past, which I rented in high school and screened with my friends from our Gay-Straight Alliance. That film actually occasioned one of my first acts of organizing; I ran a letter-writing campaign to have our local Blockbuster stop preventing minors from renting it, because, for pete's sake, it's a historical documentary. (It was also so true to queer organizing: I ran it with my girlfriend and my ex-girlfriend. One of whom you've met.) My high school was an excellent suburban public high school, but it taught us barely anything of twentieth-century history, let alone anything significant about the civil rights movement. So this was the beginning of my education that the history of the civil rights movement was more than "then Martin Luther King, Jr., convinced America to stop being racist." And my education that movements were complicated, which was the best lesson I could have learned for my few years working in them.

Since then, I've studied Rustin's works. His voice as a writer speaks to me. His politics--a little socialist, a lot Quaker, concerned both with the purity of ideals and the practical elements of actually making change--is one I recognize when I look in the mirror. And his history is one that needs remembering.

Happy Bayard Rustin Day.

Some links:

But I was chatting with a friend the other day. She was talking about the speech she gives to her son (who is mixed race and identifiably black, and who she is raising in a very white town) about Martin Luther King, Jr. And her speech is largely about how he was the most palatable of the major leaders of black movements, the one the white mainstream could accept. "And that," she ends the speech, "is why we don't have Malcom X Day, or Bayard Rustin Day."

Martin Luther King, Jr., and Bayard Rustin, wearing some snazzy suits.

In honor of her son and mine, I'm making today Bayard Rustin Day.

Bayard Rustin was raised in West Chester, PA, not 20 miles from where my parents live. Like many from Eastern Pennsylvania, he was raised with a Quaker influence. As an adult, he belonged to the same Quarterly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends as I do (though not the same Monthly Meeting). He was a labor leader, a communist, a draft resister. He helped to found the Congress of Racial Equality and the Southern Christian Leadership Council. He studied Gandhian nonviolence and taught its principles to Martin Luther King, Jr., and he organized the March on Washington for Jobs and Equality. He was fired from organizing jobs because he was gay, more than once.

More than any of this, he was a theorist and analyst of the movements he was a part of. He wanted to push all the movements he was involved with towards a broader, integrated goal of liberation from oppression in all its forms: not merely racism, or sexism, or anti-Semitism, or homophobia, but the intergrated system of oppression and suffering rooted in class and identity. This broad progressive agenda was difficult to get mainstream organizations to accept. He didn't care that he would never be the one out front in the crowd. He spoke his truth, and he argued for his cause, and he fought for justice. And that was enough.

I first learned about Rustin from the film Out of the Past, which I rented in high school and screened with my friends from our Gay-Straight Alliance. That film actually occasioned one of my first acts of organizing; I ran a letter-writing campaign to have our local Blockbuster stop preventing minors from renting it, because, for pete's sake, it's a historical documentary. (It was also so true to queer organizing: I ran it with my girlfriend and my ex-girlfriend. One of whom you've met.) My high school was an excellent suburban public high school, but it taught us barely anything of twentieth-century history, let alone anything significant about the civil rights movement. So this was the beginning of my education that the history of the civil rights movement was more than "then Martin Luther King, Jr., convinced America to stop being racist." And my education that movements were complicated, which was the best lesson I could have learned for my few years working in them.

Since then, I've studied Rustin's works. His voice as a writer speaks to me. His politics--a little socialist, a lot Quaker, concerned both with the purity of ideals and the practical elements of actually making change--is one I recognize when I look in the mirror. And his history is one that needs remembering.

Happy Bayard Rustin Day.

Some links:

- The wikipedia entry on him is not bad.

- Here's a bio.

- Here is my favorite essay of his: From Protest to Politics.

- OK, here's a second favorite: Black Power and Coalition Politics.

- Rustin was one of the main authors of this pamphlet, but his participation was kept quiet because of the worry that it would lose credibility if an openly gay man was identified as its author. Speak Truth to Power: A Quaker Search for an Alternative to Violence.