Final Project from Media Literacy Class

I wanted to share my final project for the previous class I took with Professor Kelley. It was a photo essay showing how the subtleties of image manipulation, photoediting and desktop publishing can take the same seemingly objective image and turn it into a subjective vehicle for a specific message. In other words, even a "factual" photograph is not necessarily an objective account!

The War in Iraq: Noble Mission or Brutal Evil?

PART 1: THE POSTERS

In order to achieve the full effect of the project, please view the two following images and register your gut reaction to each of them before proceeding to the accompanying text.

IMAGE A:

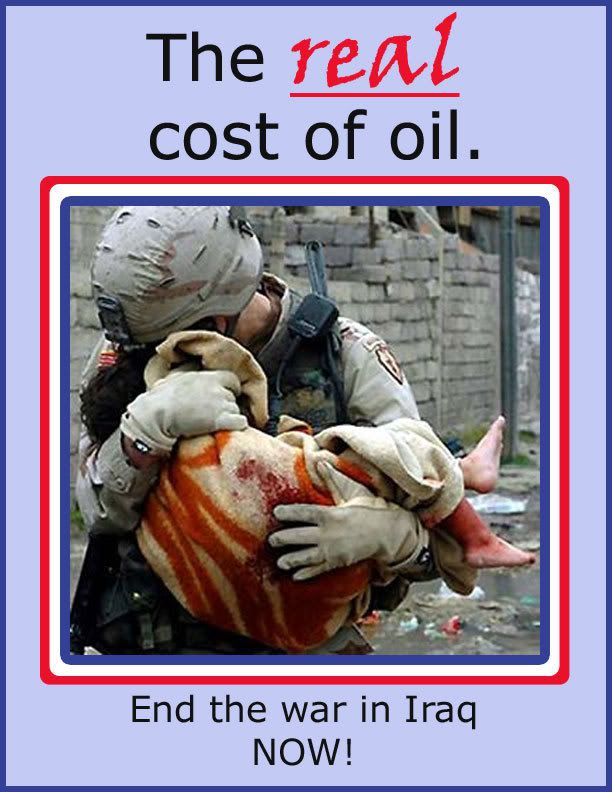

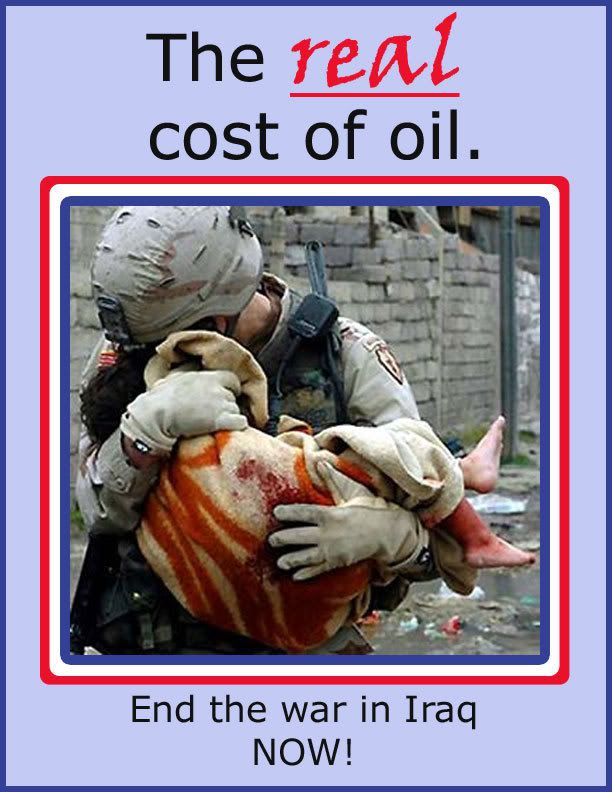

IMAGE B

PART 2: THE TEXT

“Media have tremendous power in setting cultural guidelines and in shaping political discourse.”

How To Detect Bias In the Media

www.fair.org

Thesis Statement

The intent of this essay is to demonstrate the power of the media in portraying events or news. Through subtle differences in imagery, wording, image cropping and graphics, I will use the exact same image and manipulate its publishing to convey two opposite messages: one pro-war, the other anti-war. ( Image found through Google Image search. The name of the photographer was not available, so author cannot be properly credited.)

Introduction

Throughout the entire semester, the Media Literacy course has taught us how to distinguish between cold, hard facts and their interpretation by possibly biased media. During this essay, I’d like to explore the methods used by the media (in this case, visual media) to imbue the objective facts with a subjective value judgment.

In the pages above, you viewed two posters. Before viewing the images, you were asked to register your “gut” reaction to each poster. Please do so without detailed inspection of each one. Simply look at them as you would a billboard when you are driving down the highway. If you haven’t yet done so, please take a moment now to capture your reaction to each poster before continuing.

I’m sure your reaction to each of them was vastly different, as I’m sure it was clear to you which poster was a pro-war sentiment and which was anti-war. Depending on your own views of the war and what feelings you have, one poster probably made you react positively and in agreement, while the other one caused you to react negatively, disagree, and possibly even feel anger. Perhaps, even, if the message was powerful enough and the posters well-executed enough, the ultimate goal of each of one would be reached and your opinion of the subject (the war) would be molded to fit the intention of the poster’s author.

In the body of this essay, titled “Analyzing the Methods Used to Elicit Reaction”, I will explore how a combination of graphics, words and image manipulation were used to convey these two polar opposite views. As you read along the next section, refer to the images often, so that each point is clear. Perhaps there will be subtle yet deliberately chosen elements that you hadn’t noticed at first glance, but which all together add to the subjective viewpoint that was intended to come through each poster.

Analyzing the Methods Used to Elicit Reaction

“Framing (media) is the process by which someone packages a group of facts to create a story.”

Lawrence Wallack, Lori Dorfman, and Makani Themba

Media Advocacy and Public Health: Power for Prevention

In this section, we will explore the verbal and non-verbal methods used to construct the posters, conveying not only an image but also a specific ideology and subjective opinion.

The different elements that were chosen for such a purpose are not only the main photograph, but also graphics, language, and photo manipulation.

1. Graphics

a. Colors

In both posters, the traditional American colors of red, white and blue are used. This is of course not a coincidence or a breezy preference. It’s a calculated attempt to imbue patriotic fervor to the corresponding message, implying that agreeing with the poster’s message is “the patriotic thing to do.”

Image A, the “pro war” poster, uses the colors exclusively, so as to tie in with the general message that supporting the troops equals supporting the war, which in turn is equivalent with being patriotic.

Image B, the “anti war” poster, adds the use of light blue as a background. Light blue was chosen to represent the traditional color for a baby boy, thus tugging at the viewer’s heart strings, a subtle reminder that this child, who appears to be dead or gravely injured, was someone’s cherished baby boy. This hints in a very delicate way at the pain the parents or extended family of the child feel at the untimely loss of the young boy’s life (or physical wellbeing.) The red, white and blue of the border framing the photo itself tries to convey that it’s also patriotic to yearn for peace.

b. Graphic Elements

In Image A, the use of white stars in a banner over the top and the bottom of the poster evoke the stars on the American flag, subliminally adding to the patriotic feel of the message, implying that the “all-American” way to feel is to support the war in Iraq.

Image B uses bands of red, white and blue in the frame around the photograph to evoke the stripes of the American flag, trying to convey a similar, yet less obvious, feeling of patriotism.

c. Text Font

In Image A, the font used is large, bold, in a very attention-getting color (red), and somewhat blocky, evoking, to a certain degree, the old “Uncle Sam Wants You” posters. This is a nod to another historic time of war, World War I, a war in which the U.S. was ultimate victorious, a war that brought about many reportedly positive changes in the world. This font is intended to re-awaken patriotic fervor such as that exhibited during World War I.

In Image B, most of the font is sober, a basic Arial in black. But the word “real” is in a ragged, red, underlined font that is meant to evoke images of slashing, violence, and blood. The fact that the rest of the language is in the basic black Arial makes this one word stand out in tremendous contrast, underlining, quite literally, the violent aspect of the photo, as opposed to the subtler undercurrent of tenderness and heartache (on the soldier’s part). This one word, this carefully selected font, and the color of the word are all pointing at the poster’s message: the casualties of wartime violence are not just soldiers.

2. Language

a. Loaded words

The article How To Detect Bias in The Media, found on www.fair.org, explains, “When media adopt loaded terminology, they help shape public opinion (…) (some) language chosen gives people an inaccurate impression of the issue, program or community.”

In other words, the use of certain words is almost guaranteed to provoke a certain emotion. Image A uses the buzz-word “heroes” (instead of troops) to raise the status of soldiers in a viewer’s mind to one of supreme courage and selflessness. Another loaded word in Image A is in the text below the image. The word is “saving”, denoting that the war is a mission of liberation and noble purpose.

In Image B, the buzz word is “oil.” This poster wants the public to think that the war’s only purpose is to gain control of large oil supplies. The word “oil” brings to mind wealthy, powerful companies that have been known to use dishonest methods to make profits. This poster’s use of the word denotes that the war is nothing but a violent act to support a selfish pursuit of money, riches and power.

b. Writing Style

The writing style in both posters is sensationalist, using words and sentence construction designed to catch the viewer’s eye and provoke an instinctive reaction. It’s not designed to cause the viewer to question values but rather to have a knee-jerk response to the poster.

c. Tone

The tone of both posters is commanding, like an order, with no room for questioning or disagreement.

Image A “instructs” the viewer to “Support Our Heroes”, with no sue of words such as “if” or “when”. Simply “Support” them, just do it, no questions allowed.

Similarly, Image B tells us to “End the war in Iraq NOW”, a clear demand with no room for disagreement.

3. Photo Manipulation

a. Cropping

Image A uses the photo in its totality, including the ruins of a city in the background, to provide context for the boy’s injuries. It shows clearly how the child sustained the harm to his body, laying to rest any conjecture as to who might have hurt him. This additional background also provides an alternative focus for the viewer’s eye, in effect “diluting” the horror of a young child wrapped in a blanket seeped in blood.

In contrast, Image B features a cropped version of the same image. The photograph was not manipulated or edited in any other way than through cropping. In this composition, the lifeless body of the child is the only thing the eye can focus on, a “close up” of his limp feet and the blood stain on the blanket. By removing the background of the photo, not only does the horrific image of the child become “concentrated”, but also, in the absence of context, it leaves the viewer’s imagination open to interpret the circumstances of the child’s death (or injuries). The viewer could potentially conjure up the scenario of soldiers storming into the child’s home and opening fire, or much more horrible alternatives. The cropping is a deliberate manipulation of the focus of the photograph as well as the absence of its context.

Note: Originally, I intended to crop the photograph for this poster to include the soldier’s weapon. This was to underscore the violent nature of the image and to open the viewer’s mind to possibilities of injuries at the direct hands of the soldier and his “big scary gun”. However, the proportions of the photo made me have to choose between including the weapon or including the child’s feet. I chose to feet to evoke a response of tenderness because of their small size, the somewhat chubby roundness that is subliminally associated with babies and toddlers, thus once again causing that “tug of the heart strings” in the viewer, especially if the viewer is a parent and even more so, a parent of a small child.

b. Framing

A simple technique that we might not always be aware of is how the graphic frame of a certain image might add or detract attention to it.

In Image A, the thin red line framing the photograph is not very constrictive or attention-getting, letting the viewer’s eye wander, blending the photograph with its background, the patriotic colors, the stars, the text. This, in effect, also “dilutes” the impact of the violence in the image, letting us have alternative focus when viewing the poster.

In Image B, the photograph is very noticeably framed with the patriotic “stripes” of color. This clearly separates the photograph from its background to direct the focus only to its subject, providing no alternative area for the eye to wander to. The frame also draws our eye to the center, stressing this area to be the very essence of the message the poster is trying to convey.

Conclusion

As has been demonstrated, the different elements used to create each poster all add up to a message, clear and unequivocal, of the author’s opinion. Either poster could be easily used for its corresponding message’s campaign, and there’d be no doubt which is which.

If we were to translate the posters into written media, perhaps a sensationalist blurb on a newspaper or magazine article describing the death of this child in Iraq, I believe we could similarly use words to focus the emphasis of the message in different places.

Image A could just as well be a blurb that would read something like this:

“In the midst of an enemy attack and at the risk of great bodily harm to himself, U.S. Army Sgt. John Smith ran back into the epicenter of the destruction to try and rescue an injured Iraqi child. The soldier reports that he heroically tried to revive the child for hours, until a U.S. Army medic finally pronounced the death. Sgt. Smith expresses great grief for the loss of this child’s life and assures the public that such occurrences are so rare that they still evoke strong feelings. ‘These things happen so rarely,’ he says, ‘But they really get to you.’

However, he admonishes, as tragic as this is, we should not lose sight of the true objective of the mission the troops carry out in the Middle East: the preservation of world freedom and the liberation of Iraqi people from the rule of a ruthless monster: Saddam Hussein.”

This writing is clearly biased, just as Image A is, towards defending the war and its purpose, and focuses emphasis on the humanity and courage of the soldier (fictiously named Sgt. John Smith.)

Image B could correspond to a blurb such as the following:

“Another bomb shattered the peace of a small Iraqi village yesterday, flooding its residents yet again with terror and destruction. One of the many innocent victims was a young boy, seen here carried by Sgt. John Smith. This child’s parents are just the latest addition to a long list of families that have been torn apart by the horrors of a war waged on their territory, a war that they had no say in, a war that has brought them nothing but heartbreak and loss. ‘These things happen,’ Sgt. Smith said in what is surely a much glibber mood than the little boy’s family will feel in years.”

This would place emphasis, as does Image B, on the violence, the loss of human life, the killing of little children. It takes the fictitious Sgt. Smith’s quote and uses only the first part of it, completely changing the perceived meaning of it.

In conclusion, it’s important to say that a piece of news, a portrayal of an event, is seldom exclusively objective. It can often be interpreted in many different ways, recounted with different messages, used for different ulterior ideologies. The media is not always an objective reporter of news. The author of a piece, be it words, still images, or film, can use a myriad subtle tools to subliminally construct a judgment of value in the consumer.

Through competence in media literacy we can learn to read between the lines, to distinguish fact from propaganda, and become more informed and less vulnerable to the “spins” on what we read, see, or hear.

The War in Iraq: Noble Mission or Brutal Evil?

PART 1: THE POSTERS

In order to achieve the full effect of the project, please view the two following images and register your gut reaction to each of them before proceeding to the accompanying text.

IMAGE A:

IMAGE B

PART 2: THE TEXT

“Media have tremendous power in setting cultural guidelines and in shaping political discourse.”

How To Detect Bias In the Media

www.fair.org

Thesis Statement

The intent of this essay is to demonstrate the power of the media in portraying events or news. Through subtle differences in imagery, wording, image cropping and graphics, I will use the exact same image and manipulate its publishing to convey two opposite messages: one pro-war, the other anti-war. ( Image found through Google Image search. The name of the photographer was not available, so author cannot be properly credited.)

Introduction

Throughout the entire semester, the Media Literacy course has taught us how to distinguish between cold, hard facts and their interpretation by possibly biased media. During this essay, I’d like to explore the methods used by the media (in this case, visual media) to imbue the objective facts with a subjective value judgment.

In the pages above, you viewed two posters. Before viewing the images, you were asked to register your “gut” reaction to each poster. Please do so without detailed inspection of each one. Simply look at them as you would a billboard when you are driving down the highway. If you haven’t yet done so, please take a moment now to capture your reaction to each poster before continuing.

I’m sure your reaction to each of them was vastly different, as I’m sure it was clear to you which poster was a pro-war sentiment and which was anti-war. Depending on your own views of the war and what feelings you have, one poster probably made you react positively and in agreement, while the other one caused you to react negatively, disagree, and possibly even feel anger. Perhaps, even, if the message was powerful enough and the posters well-executed enough, the ultimate goal of each of one would be reached and your opinion of the subject (the war) would be molded to fit the intention of the poster’s author.

In the body of this essay, titled “Analyzing the Methods Used to Elicit Reaction”, I will explore how a combination of graphics, words and image manipulation were used to convey these two polar opposite views. As you read along the next section, refer to the images often, so that each point is clear. Perhaps there will be subtle yet deliberately chosen elements that you hadn’t noticed at first glance, but which all together add to the subjective viewpoint that was intended to come through each poster.

Analyzing the Methods Used to Elicit Reaction

“Framing (media) is the process by which someone packages a group of facts to create a story.”

Lawrence Wallack, Lori Dorfman, and Makani Themba

Media Advocacy and Public Health: Power for Prevention

In this section, we will explore the verbal and non-verbal methods used to construct the posters, conveying not only an image but also a specific ideology and subjective opinion.

The different elements that were chosen for such a purpose are not only the main photograph, but also graphics, language, and photo manipulation.

1. Graphics

a. Colors

In both posters, the traditional American colors of red, white and blue are used. This is of course not a coincidence or a breezy preference. It’s a calculated attempt to imbue patriotic fervor to the corresponding message, implying that agreeing with the poster’s message is “the patriotic thing to do.”

Image A, the “pro war” poster, uses the colors exclusively, so as to tie in with the general message that supporting the troops equals supporting the war, which in turn is equivalent with being patriotic.

Image B, the “anti war” poster, adds the use of light blue as a background. Light blue was chosen to represent the traditional color for a baby boy, thus tugging at the viewer’s heart strings, a subtle reminder that this child, who appears to be dead or gravely injured, was someone’s cherished baby boy. This hints in a very delicate way at the pain the parents or extended family of the child feel at the untimely loss of the young boy’s life (or physical wellbeing.) The red, white and blue of the border framing the photo itself tries to convey that it’s also patriotic to yearn for peace.

b. Graphic Elements

In Image A, the use of white stars in a banner over the top and the bottom of the poster evoke the stars on the American flag, subliminally adding to the patriotic feel of the message, implying that the “all-American” way to feel is to support the war in Iraq.

Image B uses bands of red, white and blue in the frame around the photograph to evoke the stripes of the American flag, trying to convey a similar, yet less obvious, feeling of patriotism.

c. Text Font

In Image A, the font used is large, bold, in a very attention-getting color (red), and somewhat blocky, evoking, to a certain degree, the old “Uncle Sam Wants You” posters. This is a nod to another historic time of war, World War I, a war in which the U.S. was ultimate victorious, a war that brought about many reportedly positive changes in the world. This font is intended to re-awaken patriotic fervor such as that exhibited during World War I.

In Image B, most of the font is sober, a basic Arial in black. But the word “real” is in a ragged, red, underlined font that is meant to evoke images of slashing, violence, and blood. The fact that the rest of the language is in the basic black Arial makes this one word stand out in tremendous contrast, underlining, quite literally, the violent aspect of the photo, as opposed to the subtler undercurrent of tenderness and heartache (on the soldier’s part). This one word, this carefully selected font, and the color of the word are all pointing at the poster’s message: the casualties of wartime violence are not just soldiers.

2. Language

a. Loaded words

The article How To Detect Bias in The Media, found on www.fair.org, explains, “When media adopt loaded terminology, they help shape public opinion (…) (some) language chosen gives people an inaccurate impression of the issue, program or community.”

In other words, the use of certain words is almost guaranteed to provoke a certain emotion. Image A uses the buzz-word “heroes” (instead of troops) to raise the status of soldiers in a viewer’s mind to one of supreme courage and selflessness. Another loaded word in Image A is in the text below the image. The word is “saving”, denoting that the war is a mission of liberation and noble purpose.

In Image B, the buzz word is “oil.” This poster wants the public to think that the war’s only purpose is to gain control of large oil supplies. The word “oil” brings to mind wealthy, powerful companies that have been known to use dishonest methods to make profits. This poster’s use of the word denotes that the war is nothing but a violent act to support a selfish pursuit of money, riches and power.

b. Writing Style

The writing style in both posters is sensationalist, using words and sentence construction designed to catch the viewer’s eye and provoke an instinctive reaction. It’s not designed to cause the viewer to question values but rather to have a knee-jerk response to the poster.

c. Tone

The tone of both posters is commanding, like an order, with no room for questioning or disagreement.

Image A “instructs” the viewer to “Support Our Heroes”, with no sue of words such as “if” or “when”. Simply “Support” them, just do it, no questions allowed.

Similarly, Image B tells us to “End the war in Iraq NOW”, a clear demand with no room for disagreement.

3. Photo Manipulation

a. Cropping

Image A uses the photo in its totality, including the ruins of a city in the background, to provide context for the boy’s injuries. It shows clearly how the child sustained the harm to his body, laying to rest any conjecture as to who might have hurt him. This additional background also provides an alternative focus for the viewer’s eye, in effect “diluting” the horror of a young child wrapped in a blanket seeped in blood.

In contrast, Image B features a cropped version of the same image. The photograph was not manipulated or edited in any other way than through cropping. In this composition, the lifeless body of the child is the only thing the eye can focus on, a “close up” of his limp feet and the blood stain on the blanket. By removing the background of the photo, not only does the horrific image of the child become “concentrated”, but also, in the absence of context, it leaves the viewer’s imagination open to interpret the circumstances of the child’s death (or injuries). The viewer could potentially conjure up the scenario of soldiers storming into the child’s home and opening fire, or much more horrible alternatives. The cropping is a deliberate manipulation of the focus of the photograph as well as the absence of its context.

Note: Originally, I intended to crop the photograph for this poster to include the soldier’s weapon. This was to underscore the violent nature of the image and to open the viewer’s mind to possibilities of injuries at the direct hands of the soldier and his “big scary gun”. However, the proportions of the photo made me have to choose between including the weapon or including the child’s feet. I chose to feet to evoke a response of tenderness because of their small size, the somewhat chubby roundness that is subliminally associated with babies and toddlers, thus once again causing that “tug of the heart strings” in the viewer, especially if the viewer is a parent and even more so, a parent of a small child.

b. Framing

A simple technique that we might not always be aware of is how the graphic frame of a certain image might add or detract attention to it.

In Image A, the thin red line framing the photograph is not very constrictive or attention-getting, letting the viewer’s eye wander, blending the photograph with its background, the patriotic colors, the stars, the text. This, in effect, also “dilutes” the impact of the violence in the image, letting us have alternative focus when viewing the poster.

In Image B, the photograph is very noticeably framed with the patriotic “stripes” of color. This clearly separates the photograph from its background to direct the focus only to its subject, providing no alternative area for the eye to wander to. The frame also draws our eye to the center, stressing this area to be the very essence of the message the poster is trying to convey.

Conclusion

As has been demonstrated, the different elements used to create each poster all add up to a message, clear and unequivocal, of the author’s opinion. Either poster could be easily used for its corresponding message’s campaign, and there’d be no doubt which is which.

If we were to translate the posters into written media, perhaps a sensationalist blurb on a newspaper or magazine article describing the death of this child in Iraq, I believe we could similarly use words to focus the emphasis of the message in different places.

Image A could just as well be a blurb that would read something like this:

“In the midst of an enemy attack and at the risk of great bodily harm to himself, U.S. Army Sgt. John Smith ran back into the epicenter of the destruction to try and rescue an injured Iraqi child. The soldier reports that he heroically tried to revive the child for hours, until a U.S. Army medic finally pronounced the death. Sgt. Smith expresses great grief for the loss of this child’s life and assures the public that such occurrences are so rare that they still evoke strong feelings. ‘These things happen so rarely,’ he says, ‘But they really get to you.’

However, he admonishes, as tragic as this is, we should not lose sight of the true objective of the mission the troops carry out in the Middle East: the preservation of world freedom and the liberation of Iraqi people from the rule of a ruthless monster: Saddam Hussein.”

This writing is clearly biased, just as Image A is, towards defending the war and its purpose, and focuses emphasis on the humanity and courage of the soldier (fictiously named Sgt. John Smith.)

Image B could correspond to a blurb such as the following:

“Another bomb shattered the peace of a small Iraqi village yesterday, flooding its residents yet again with terror and destruction. One of the many innocent victims was a young boy, seen here carried by Sgt. John Smith. This child’s parents are just the latest addition to a long list of families that have been torn apart by the horrors of a war waged on their territory, a war that they had no say in, a war that has brought them nothing but heartbreak and loss. ‘These things happen,’ Sgt. Smith said in what is surely a much glibber mood than the little boy’s family will feel in years.”

This would place emphasis, as does Image B, on the violence, the loss of human life, the killing of little children. It takes the fictitious Sgt. Smith’s quote and uses only the first part of it, completely changing the perceived meaning of it.

In conclusion, it’s important to say that a piece of news, a portrayal of an event, is seldom exclusively objective. It can often be interpreted in many different ways, recounted with different messages, used for different ulterior ideologies. The media is not always an objective reporter of news. The author of a piece, be it words, still images, or film, can use a myriad subtle tools to subliminally construct a judgment of value in the consumer.

Through competence in media literacy we can learn to read between the lines, to distinguish fact from propaganda, and become more informed and less vulnerable to the “spins” on what we read, see, or hear.