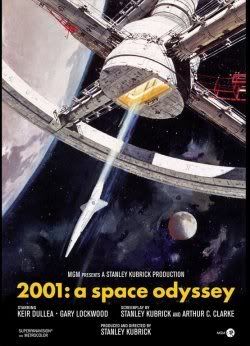

A Writer's Odyssey: Beyond 2001

Arthur C. Clarke died today, at the age of 90.

It’s a bad week for film buffs. Just a few days ago Anthony Minghella died.

I took out my new DVD of 2001: A Space Odyssey and watched it again.

It’s a digitally remastered copy. Clear and clean, with great sound. I don’t really ever remember watching it this clearly. I’ve seen it on TV many times in edited and technically terrible condition. This new 2-disc special edition I got a month ago is about as clear as it’s ever going to be, I guess. It’s wonderful. I’m sure Mr. Clarke had a copy of this before he died, and maybe marveled at the digital remastering himself.

No scratches, no jumps. Complete, restored, perfect video in Super Panavision. And the sound, in Dolby Digital, was as crisp as the day it was recorded. Johann Strauss’ The Blue Danube never sounded so beautiful. And the labored breathing of Dave Bowman in his spacesuit as he took apart HAL’s memory circuits spoke volumes without using a single word.

It was a slow movie, and it took its time. The first three minutes is just music, no video, as is the end of the film. Today’s viewers with next-to-no attention spans would go apeshit and jeer and hoot at the projectionist to fix the glitch. There’s even a five-minute intermission in the middle, it’s that old-fashioned. The first 30 minutes of the 148-minute film is practically a silent movie, and the much of the movie is unexplained, with odd cuts and dissolves, title cards and muted acting. On the other side of the coin, the special effects were ground-breaking, even by today’s standards. It’s an odd movie, one of the oddest.

The storyline was oddly thin: an alien slab is found on the moon, and a secret mission is sent to investigate the signal it sends to Jupiter. The exposition came in big odd chunks, almost four separate short films: The Caveman Ooga-Booga sequence with The Bone. The Blue Danube/Heywood Floyd Goes to The Moon sequence. The HAL Goes Bonkers sequence. Then finally, Dave Bowman’s Light-Show Trip. If you’ve seen it before, you can just skip to the chunks you liked (which for me was the HAL Goes Bonkers part) and the film still works.

For the movie-centric fan, it was a Stanley Kubrick piece. For the book-centric ones, like me, it was more an Arthur C. Clarke piece. But for both men, 2001: A Space Odyssey looms large in their legacy, the biggest spike in either man’s creative timeline.

I remember watching it when I was seven or eight years old, when it first came out sometime in the late sixties, in an actual Cinerama-equipped movie theater. (Yes, I’m that old.)

It was Nation Theater in Cubao, near the old C.O.D. Department Store where we used to watch the animated Christmas display every year. Nation Theater was one of two Cinerama-equipped theaters in the city. The other was Cinerama Theater itself, on the corner of Avenida Rizal and Quezon Boulevard, just before Plaza Miranda. It was the moviehouse that was on the corner right above the underpass, and is now a mall. Where Nation was is now literally a large hole in the ground in Cubao.

Cinerama is a special movie projection system that uses three screens for an extra large format. Three separate projectors in sync are required to project the film. Even more interesting is that the three screen-wide projection area isn’t flat. It’s curved, concave from left to right; it’s like you’re watching from inside a can and the movie is being projected on the inside wall of the can, half-surrounding the viewer. Today, without the curved screen, it was just Super Panavision.

It’s cool, but mainly a gimmick. Saw a few more movies in the format - a western, some war movies. War and Peace. After a few years it died a natural death, but Nation kept showing regular movies in Cinerama mode. I saw Close Encounters of the Third Kind there on that big, curved screen, and even if it wasn’t made for the format, it added a certain epic look; imagine the Devil’s Tower sequences on that gigantic screen.

2001 was made for Cinerama, and I was fortunate enough to experience it the way Clarke and director Stanley Kubrick composed the film and meant for it to be seen. Watching it now on a large TV from a digitally remastered format, the movie stands well without the Cinerama gimmick.

But I do remember how marvelous that gimmick was, especially to a seven year old. That scene where Gary Lockwood jogs and exercises in the spinning circular room that uses centrifugal force to create artificial gravity looked fantastic in Cinerama. Kubrick’s camera angles and composition was made for the Cinerama format and it burned into the mind of the kid that was me. Seeing it again brought back strong memories. Like seeing that breathtaking, totally unexpected three-million year jump-cut from the twirling femur to the gliding spaceship with the Strauss music.

It was what got me into science fiction in the first place, and a kid could do no better than being tag-teamed by Clarke and Kubrick. I had just learned to read books, and was starting a classic education - Jules Verne, H.G. Wells and the like, when I got to see 2001. That movie jump-started my love and appreciation for the genre, and fast-fowarded my education light-years ahead in the space of a little over two hours. A bit like Dave Bowman’s light-show trip near the end of the film.

That seven-year-old didn’t understand that movie on the bigger than big screen. And to some point today, at 46, I still don’t. I don’t mind, I’m in good company. An added feature on the DVD, some documentaries, had people like Steven Spielberg admitting they still didn’t get a lot of it, but sensed the power and structure behind the cryptic images, and the implications of the concepts. To some extent, the kid did too, which is why he would be caught up by the siren song of sci-fi for the rest of his life.

The movie is called Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, but Arthur C. Clarke should be credited as much, if not more, for the movie. Stanley created the visuals, but the ideas, Clarke’s, stayed with me longer. Kubrick didn’t even like science fiction. Later in life I’d cut my teeth on Clarke’s books. Rendezvous With Rama, for example, boggled my mind and had me thinking for weeks.

Let’s be fair. Beside today’s firebrands and stupendously imaginative, creative and talented sci-fi writers, Clarke is a dinosaur. A slow, often pedantic style of writing, an old-fashioned manner, he’d be a bit unremarkable beside today’s household names with their stream-of-consciousness narratives, their wild, improbable concepts and action set pieces that went like gangbusters. But these household names are what they are because Clarke helped put them there. Serious, thoughtful, intelligent fiction, abstract ideas made concrete, forward thinking - Clarke was there first, and everyone sought to catch up.

He’s one of those folk you’d expect to always be there, a constant presence, coming out steadily with books with mature, thought-through ideas, explained and told rationally and with authority, year after year. Something science-fictiony happens in the news and they all try to get a Clarke soundbite from Sri Lanka, where he relocated, to see what he thinks. But no more. He’s gone now.

Arthur C. Clarke died forty years after the release of 2001, and seven years after their movie stopped becoming forward-looking and became quaintly retro, at least title-wise. While a lot of the tech didn’t come true as he had envisioned, his ideas, on the whole, are still relevant and current, not just for his movie with Kubrick, but for his other stories and novels.

I learned of his death today from a friend, another sci-fi nut, who texted me what at first I thought was just a joke:

Arthur C. Clarke went to heaven. There was a sign at the gates that said “No writers or directors allowed.” St. Peter said, “Sorry, man, but no way.” Suddenly a scruffy-looking bearded man passed him and was let through quickly. Arthur said “Hey! That’s Stanley Kubrick! Why’d you let him in?” St. Peter said “Nope. That wasn’t Kubrick, that was God. He only THINKS he’s Kubrick.” R.I.P. Arthur C. Clarke. March 19, 2008.

It was irreverent, it was disrespectful, but it was apt.

Arthur C. Clarke would have loved it.