The Shadow Box

by applegnat

Milano, 1997.

It is the first time in thirteen years that the San Siro makes Paolo feel outright claustrophobic. He’s seen it this full before - he sneaked into the David Bowie concert in ’87 in spite of his father’s forbidding it - but he’s never been at the centre of such a gargantuan wave of attention in his life. It isn’t even directed at him. He huddles in the centre of a crush of teammates and club officials, as the shrieking, stamping largeness of the noise sloughs off the pillars and roars over the podium like it’s never done before, pounding under his feet like a bass line thumping straight up from the core of the earth. From beside him, Franco slips out to take the microphone from the president. Paolo watches him shrink a little as he breathes, away from it, and then square his shoulders, the way he always does once the football is over and the press conferences begin, and raise his head to the greying evening sky, the eighty thousand in the skyscraper seats who have come to bid him farewell. He clears his throat, faintly, over the PA system. The noise hums into a marginal softness.

“Thank you,” Franco says. “It’s time for the captain to say goodbye.”

He then hands the mic back to the president, who hasn’t had time to rearrange his face out of his expectant smile. He swings around once, slowly, hands raised to the crowd, and bows his head.

“What?” Paolo says, in the split second of dead silence. “What?”

Billy turns to answer him, but shuts his mouth as the applause cracks open above their heads, and shrugs.

“I thought you were giving a speech,” Billy says later, in the dressing room.

“I did,” Franco says, rummaging in his locker.

“A real speech,” says Billy. “With more than ten words in it.”

“I had one,” Franco says, smiling and matter-of-fact. He talks quickly, shortly, the way he always does to cover his nervousness at being unable to explain something. “I didn’t trust myself.”

Paolo, retying his shoelaces on a bench, looks up, and then straightens as Franco comes towards him. He actually gives it to him this time, presses it into his hand and closes his fingers over it.

“Before I forget,” Franco says. He looks at the stripes on Paolo’s jersey for a moment, then looks up and smiles.

“I,” Paolo says. “I.”

“Do well,” Franco says, and squeezes his shoulder.

“I will,” Paolo says faintly. He reaches out, impulsively, to hug the other man. Don't go, he thinks.

"Don't worry," he says.

"We should go back out,” Franco says, crushing Paolo's breath out of his ribs for a moment before pulling away. He jogs back out into the grey, smoggy dusk outside. Billy narrows his eyes at Paolo, winks quickly, and then hurries after Franco. Paolo follows him slowly to the entrance, and then looks down at his hands, at the armband twisting in his fingers. He turns back inside, straps it on, and tries to decide how it feels, if it feels. If he’s going to remember this moment for the rest of his life.

But he’s played football for fourteen years now, and he thinks to himself that in another fourteen years it won’t matter to anyone, not even to himself, whether he does or not. So he takes it off, stuffs it into his pocket, and goes out to join the rest of them. Night has fallen, and everything before him sharpens into a blinding brightness as the floodlights come on one by one.

*_*_*_*

Milano, 1985.

Your home away from home, a voice announces in Paolo’s head, when he comes to Milan. Alright, then. School is raucous and unruly, one long lunch-break filled with rising dust and sandwiches and boys shouting at each other on the yellowing field outside his classroom. Pass the ball, pass the ball, the fucking ball - oh, fuck. Give it here. Give! Let’s get out of here.

Home is quiet, held together by routine silences; the corners close in on minute, tacit understandings and conversations substituted perfectly by the clink of cutlery, sneakers or stilletoes tapping on the stairs, piano scales weaving in and out of the sound of murmured multiplication tables and the chief crops of Spain, and the evening news on the television. Milan is quiet, too, quiet like that.

Shit, the announcer in Paolo’s head says, a little irritably, when the thump of his school satchel on the bench and his shoes clattering to the floor are met with no answering voices. Not this. He looks around him, at the boys hanging up their shirts in the closets, the men whipping out the creases in the newspapers, all silent, the way deaf people are silent. He pulls his kit on. It whispers around his head, and he lets it shut the changing room out for a moment, suffocating agreeably in the light. It’s the proper jersey, the first team one with MALDINI on the back, instead of the nameless youth team one. No one on the Primavera dared crack the obvious joke when his father was within hearing distance, and a father like that is never really anywhere else. Another sort of silence, Paolo realises, and pulls the shirt over his head with vicious force.

He glances up, then, to see that someone is looking at him. Damn, Costacurta - Costacurta, like an obnoxious school senior, people (girls) all over him because he’s tall and handsome and talks, full of sarcasm and urbanity and his lucky bastard eighteen year old self. Not that he deigns to talk to Paolo, of course. Paolo looks at him, mouth open, trying to say something that isn’t I want to punch you, and then feels his neck prickle as Costacurta raises an eyebrow - raises an eyebrow - at him. At him. And then nods, and walks away, leaving the undefined, unspoken challenge hanging there, as though it were no more than a perfunctory greeting.

Welcome, then, Maldini, the announcer says. Welcome. Benvenuto a Milan.

His neck prickles again and he turns. The room is emptying now, the kitted-out players filing out like commuters at the subway station. There’s no one there but the captain, who is tying his bootlaces, and not looking at Paolo. He's a small man. Moves neat and alert, like a bird, but is granite when he's still. Paolo knows who he is, of course. Everybody knows il capitano. Juve have been asking ever since they came back up to Serie A, word has it, although you wouldn't know it to look at his face. Paolo is certain everyone in the world would be able to read him like a book if Juve ever called him. Excuse me, am I speaking with Maldini? Yes? Well, Maldini, I don't know if you know, but we've been watching you. We'd like to offer you a place. Yes, we know it's an honour. Yes, you're good enough for Juventus. Yes yes. For your own sake. Yes yes. We'll send a car around next Sunday.

All his life Paolo has listened to his coaches teach him football. They have all been his father’s teammates. Mister Liedholm always calls him ‘Paolo,’ careful to make him a little more than his last name (and maybe a little less). Paolo is so grateful for it that he does everything he is asked to twice over. The mister calls the captain ‘kid,’ although Franco Baresi is twenty-four and looks older than he is. The only thing he says to Paolo on the field that day is, “Trap it with your left before you shoot.”

Paolo is so dazed at the fact that the man talked to him that he does what he is asked, finds exactly the right timing for a pass to Wilkins, and feels, for a moment, like he’s learnt everything there is to know about football.

Before the year ends, Paolo drops out of school. The sum total of his education is now his attempt at unpacking tactics and unlocking attacks in the cool, moist shade of Milanello. He leaves the house before Cesare does and returns home long after Cesare has sat down to dinner. At work they ignore each other, except for when Paolo’s subway pass expires and he needs a ride home. (“You don't carry enough money for a bus ticket?” Cesare asks.) The emptiness ebbs into his afternoons. Milan is quiet, quiet like home. Quiet, in 1985, like the aftermath of a long struggle ending in inevitable failure. Quiet because Liedholm’s voice is soft and warm, threading through the team like the languid, mazy string of a pass. Quiet because Franco Baresi plays every minute on the field with a slow, considered viciousness and snuffs out his opponents’ moves in the second before they think of them, and doesn’t talk while he does this. Paolo stops playing the announcing game in his head and starts to work harder than he’s ever worked in his life before.

But gradually the silences begin to undo themselves, like a forward line whose patience doesn’t match up to your own. It never occurs to Paolo that he imagines things when they fall into place. It’s like a good game plan; you play it for long enough and the meanings suggest themselves to you in time. Example: Franco frowns, he comes to notice, for most things. He frowns when something annoys him, or worries him, or makes him want to smile in spite of himself, or when he wants to say Good game to his teammates but can’t because they’ve dropped points. He frowns when he pays attention to Paolo. When Paolo wants to say How am I doing, am I any good, I’m really not bad, am I?, he frowns back at Franco, who never takes notice. And because Franco leads by example, the rhythm they fall into is this one, where they smile only when they mean it and observe each other quietly, with attention, not needing to be told what to do. That steel core of silence lasts them through match after match, point after dropped point, through the trough of financial crises, of which Paolo reads only the most relevant details in the deepening creases around Franco’s mouth.

The mister throws him into the championship at left-back, one weekend in January. Franco frowns at that. He mutters, “Took you long enough,” when Paolo jogs, slowly, into position.

The first time the quiet is shattered, to Paolo’s ears, is when Berlusconi finally buys them out. Gianni Rivera, who negotiates with officials and players outside Milan and stands at the touchline clutching his hair whenever he’s down at the grounds, goes tearing through the club buildings in a rage. He throws his resignation letter down at the front desk and storms out of the gates.

“This club,” he shouts at the Mister before he leaves. “This club is not for charlatans!”

“You know, I love that boy,” the Mister tells Franco later. “But quite seriously, Franco, do you think he’s alright in the head?”

Franco puts his hand on the Mister’s shoulder and presses down. “I don’t know,” he says tightly. He frowns.

Three months later the new president announces a new coach. Paolo curls up into himself and ducks behind Franco, his fingers clutching involuntarily at Franco's shirt because they are, by then, at a stage where their silence, that mutual cessation of what will almost certainly be hostilities if they escape their throats, is the only thing they have left. He reacts needlessly, he realises. The only thing Franco says to Arrigo Sacchi, nodding once, is “Mister.”

*_*_*_*

Milano, 1986.

Sacchi destroys the quiet, simply by being everywhere, demanding to know everything, talking to everyone, shouting all the time, and shouting so loudly that it takes a while for Paolo to believe him, to believe that this is for real. He is a drill sergeant, bulldozing over them the way the workers reconstruct Milanello around them, making place to accommodate rose gardens and a new medical centre. Paolo has liked to think of himself, so far, as someone with an almost pious lack of animosity for anyone (even Costacurta, with whom, he persuades himself, he’s catching up soon). He hates Sacchi with a passion that hollows him out from the inside. He chivvies and hectors and governs them in a mad, Caesarist way that sets a nervy tension thrumming through the whole team. Only Franco doesn't seem to react. He lingers, as always, in the middle, waiting for his opposition, absorbing everything they throw at him, the way he absorbs the shock of this new everything. He reacts to the loudness, the hand-wringing, the mutinous current that makes even him tiptoe around the hotwired changing room, the castigation and the praise that Sacchi reserves for him, and him alone, on the training ground, by treating them with a stolid familiarity.

It drives Paolo mad. He starts, eventually, to wreak his havoc quietly, not having acquired the talent for rebellion that makes Billy stop and answer back when Sacchi gets short with him, earning himself plenty of harangues and an odd fondness from the coach. Paolo spits out everything he can give on the field and walks away with his head down and his lips trembling with the effort of keeping quiet. He talks himself into being an adult about it. Adults walk away from arguments. Adults have a life of their own, outside of home, outside of work, somewhere with different noises and colours and an honest demand for nothing but his wages and proof of age.

Sacchi finds him there, too.

He talks to Franco these days, in sporadic, convulsive bursts. He knows him better now, he knows how to decode the frowns; and he’s eighteen and desperate.

“So he asks me if I want to be a,” he says, when they’re alone in the little kitchenette (it doesn’t exist anymore) off the dorms, where players staying over the afternoon can go to get tea, toast, glucose biscuits, stuff like that. “A.” Franco is making coffee. It’s one of the things the team has come to rely on him for, for some reason. It is as demonstrative as he will be of his affection for them. Paolo takes a sip out of the cup he pushes towards him, gets his tongue scalded. “A playboy.”

“I see,” Franco says. Franco, to Paolo’s best knowledge, has never been to a nightclub at any point of time in his footballing career.

“He comes to Sardinia, okay,” Paolo says. “He follows me. To ask me that. To ask me that. I don’t even know what to. I mean. How did he know, anyway? How does he know everything? How does he know where I went on vacation when I didn’t tell him?”

“I told him,” Franco says.

Paolo inhales the steam off his espresso in silence at that, for a while.

“Should I not have?” Franco asks.

Paolo sighs, because he wants to slap his palms on the tabletop and say Why? and What on earth do you want from me now? and Do you want me to be like you? Is that what you want? Do you think I’m not already trying hard enough?”

“I don’t know,” he murmurs, and drinks his coffee.

Franco pats him on the back, and Paolo, for the first time, manages to read it with a clarity that is so astounding it almost knocks him forwards. He recollects, with the sort of shock to which adults are supposed to be immured, that it is not only Milan, who are on trial. That good enough for Juventus means also, at some level, good enough for Milan. AC Milan. Maldini’s Milan.

One day, a little later, he comes to the end of an exercise and turns to the touchline, to see Sacchi tensed forward, fist clenched over his mouth, watching him with that familiar mad gleam in his eye.

“My God,” Sacchi says, almost to himself. “Is there anything in this world you can’t do, Maldini?”

Paolo opens and closes his mouth, feels his heels sink into the mulchy grass. Franco passes by him, pushes him forward gently. “No,” he says to Sacchi, and winks at Paolo.

*_*_*_*

Pasadena, 1994.

When the last penalty of the World Cup final flies over the crossbar, Paolo learns, for the first time in his life, what it means to give beyond expectation or capacity and still fail. He knows, intellectually, what it means to lose and be treated unfairly. But this is justice, he tells himself, and is unable to cope with the fact that all their sweat and blood, all those weeks of watching Roby grimace when someone knocks him in training, Bergomi bloody-mindedly refuse to believe that he hasn’t earned himself this tournament, and Franco pull himself out of bed at five in the morning to wear his goddamn injury down by running on it - can bring them no further than this.

He turns himself around dazedly to try and protect them, all of them, even Sacchi, from whatever is starting to beat down on them in the pinpricks of the alien afternoon sunshine. The cameras are flashing across the touchline already. The scrutiny will be glass under their feet, and he wants to sweep it out of the way before someone steps on it.

Then, Franco breaks. It takes a moment for Paolo to register the sight of Sacchi comforting him. He has never seen Sacchi comfort anyone before. He has never seen Franco cry before. He has never seen anyone cry the way Franco cries, on that day, the heaving sobs reducing him to the reality of a smallness and fragility that no one these days believes him to possess.

It eases up the lump in Paolo's own throat a little. He has a practiced brilliance for following orders, so he puts it to use now. It doesn't matter that the orders themselves don't come: he’s done it for so long that he can make them up himself. He pushes everyone back to the dressing room, waits next to Sacchi, whose voice has never sounded more grating, and says things he isn’t thinking to the dictaphones. When he arrives into the showers he’s still checking things off in his head: say the right thing, don't say anything, leave the regret behind, don’t leave the medals, don’t cry, don't look, clean up after yourself, get everyone out.

He flops on the bench in the far corner of the changing room, instead, and lies down and closes his eyes. Then he opens them, hauls himself up and looks at Franco, sitting next to him, eyes dry and face smoothed out with blankness now.

“What?” he says, when he realises Franco is saying something.

“I said it's yours now,” Franco says. He’s holding the captain’s armband out.

No, it isn’t, Paolo wants to say. “Alright,” he says instead, and takes it. “Thanks.”

There is a dim understanding, eight years on, of the way things are with them. Paolo is older now, and he slips out of Franco’s shadow because he knows what he cannot become. He realises one day along the way that he has stopped growing, and that makes him realise that he will always be taller and faster now. His accent will always be different. His name and face will never be associated only with the number on his shirt. Franco’s imperiousness would be stiff-necked bullying in Paolo, his tranquility an act of petulance. Six feet of wax and wicker attempting to behave like a chit of steel; it would be absurd.

He has a hazy memory of going to the San Siro in 1979, for the last match of the season. His father took him because Milan needed a draw to win that scudetto. He doesn’t remember why there was crowd trouble, but there was, and the match got cancelled. Rivera then came on the field with a megaphone and shouted at the stadium, demanding that they behave themselves. The stadium quieted down as one; Milan won the match and the season, the first win in Paolo’s memory. Sometimes, when he imagines himself as captain, he makes himself be like that. It’s too much of a demand on his powers of presumption, though. So he finds the middle ground. He lets go a little. He loosens his limbs and makes himself smile at least as much as he frowns. It comes home, over that year that he wins the Champions’ League and loses the World Cup, that Franco is going to leave, and leave Paolo in his place, so he thinks fast, and begins to tide things over. He starts, in self-defence, to talk. He talks long and often. He talks to the press, he talks to his players, he talks to his coaches, he talks to his opposition. He talks to referees, officials, fans, and sponsors. He talks in Italian, Spanish, French and English. Sometimes he talks to the mirror. Not a club for charlatans, Rivera said when he left. Paolo, who decides to deal in bravado until he learns how to be brave, only allows himself to think that there are far worse fates.

*_*_*_*

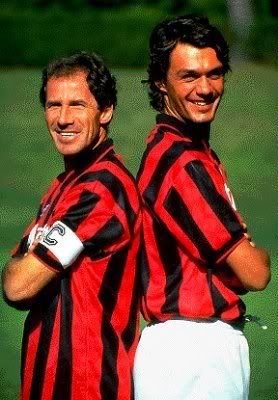

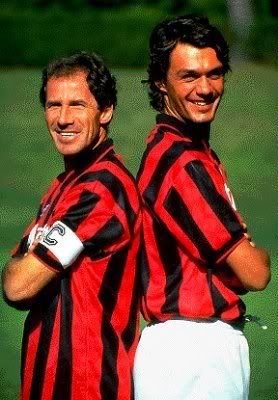

They get a photograph taken, one summer afternoon at Milanello. As friends, now, as partners and equals (or almost, as a matter of time). The photographer recommends their standing close to each other, informal, smiling, jerseys untucked.

“I can’t put my arm around your shoulder,” Franco says, looking up at Paolo. “It’ll look like a chokehold.”

“I can’t put my arm around you,” Paolo says. “It’ll look like I’m trying to crush you.”

In the end they stand with their backs to each other, arms folded, post-firm and pillar-straight. “Great!” the photographer says. “Great shot, capitano! Smile. Smile!”

“He’s talking to you, Mr Supermodel,” Franco says over his shoulder.

“I don’t need to be reminded to smile,” Paolo says, on the verge of laughter. “Of course he isn’t talking to me.”

Franco doesn’t go away, after ‘97. When he walks into Milanello people still call him ‘capitano’ instead of ‘Mister.’ Even the new signings pick it up. Paolo finds it oddly relieving, possibly because, in time, they stop calling him ‘Paolo,’ the way they stopped calling him ‘Paolino’ a decade ago, and start calling him that as well. Everyone at Milan is a creature of habit.

He phones Franco regularly, during the times that they don’t see each other. They go to dinner now and then, where Paolo is still the one who has to persuade him to eat the odd dessert. He gets into the habit of keeping the conversation up. He calls Franco when his son says he wants to play football, and lets him laugh unmercifully at his paranoia. Sometimes, they talk about the old days.

“I really wanted to play for Juventus,” Paolo tells him one night in 2001, from a rooftop overlooking the city. The season is a full month away, which allows for the bottle of wine tipping recklessly over the ice bucket on their table. “When I was a child.”

“Good enough for that?” Franco says.

“I thought so, back then,” Paolo says. It makes him laugh.

“I,” Franco says. “I went for a trial with Inter, before I came to Milan. I failed it, though.”

Paolo covers his face with a hand and laughs more, à propos of nothing. One or two people turn around to look at them. Franco smiles, and kicks him under the table to make him behave himself.

*_*_*_*

Milano, 2007.

They let him alone while they troop in and out of the showers after the derby. He sprawls on the bench, dawdling, trying to make himself forget just how angry he is. He watches them as he’s watched them for years now, coming up against cocoons that he knows so well that he can almost see them - Ricky’s trembling anger, Andrea lingering on the field in his head, still directing a pass, Rino sulking, Ambro cleaning up after them, picking up bags and ties and complaints and pleas for reassurance and putting them in their places, neat and soft-voiced. The scene is so familiar that when Franco appears in the doorway he almost doesn’t notice.

They haven’t seen each other very often in the last five years, ever since Franco returned from Fulham in 2002 (“How is London?” Paolo had asked him over the phone. “I think you’d like it better than I do,” Franco had replied, not a little dryly). He looks at him now, greying hair, training shirt, same old unobtrusiveness, and wonders, not for the first time, if that is what it will be like for him. A coaching position, a chance to fade into the wallpaper.

It seems to have been easy for Franco; he smiles more often these days. Growing old sits well on him. He walks in, nodding here, shrugging there. Billy drops something and almost bounds across the room before Gila stops him with a question. Sandro walks right into him as he stalks out of the changing room, then chokes and tries to sink through the floor in a regressive fit of embarrassment when Franco says, “Good job,” and passes him by. He stops to talk with Mauro and Carlo as everyone filters out, one by one, and then lets Billy chew his ear off a little as he lingers a while.

“You look like you want to cry,” Billy says, finally looking at Paolo, because he won’t say Fuck and this is fucked up and what the fuck is this, Paolo. Paolo draws a leg up and starts to massage his ankle. He says, “I’ll call tomorrow,” to Billy, because he doesn’t want to say Fuck off and leave me alone.

“Cry?” Franco mutters, wandering into the room as Billy sweeps out. Someone has left a pile of loose sheaves of paper scattered on the floor, diagram after useless diagram (sketched out to stave off boredom, more than anything else) doodled and discarded. He sits down on the bench next to Paolo, begins to pick them up and leaf through them, putting them in order, one by one. He doesn’t say that was rubbish and you can’t make a headed clearance properly after all this time? and you can’t play football anymore? and you’re just back from a long trip to Japan, you’ve done well, it’s been a good year and it’s one match, Paolino, you think it matters? You think anyone’s going to remember in ten years?”

“Well, cry, if you want to,” he says instead. “You have things to cry about.”

And Paolo, Paolo doesn’t cry, because he doesn’t want to say I don’t want to do this and I don’t want to give this up and I should have given it up three years ago and I’m terrified and I’m tired. He slumps over himself, then stretches out and lies down flat along the bench. The movement disorients him briefly, as he looks up at Franco, frowning into his face. It feels like twenty years ago, just after someone has cracked into his nineteen year old ankles, just before Franco helps him up and glares him back into the game. It is the sort of love Paolo has learnt to give, over the years, although never that simply and that solidly.

It's time for the captain to say goodbye, the announcer rings in his ears, clear and resonant as the voice over the PA system ten years ago. Thank you.

"You're welcome," Franco says. "Let's go home now."

He waits for Paolo to shower and change. The groundsmen start turning the lights off as they leave, slicing the San Siro into darkness.

Notes:

1. This story is based on Milan’s recent history, but knocks an occasional fact over into fictionalization where convenient, mostly in the matter of timelines [Sacchi’s following Maldini to Sardinia, for example, happened before they started training]. Apologies for the liberties. This seems like a good time to disclaim the entire story as pure and complete fiction written for love rather than profit. It is. Read more about shadow boxes here. The title in no way correlates the fic with the play of the same name.

2. Three things whose incontrovertibility seems worth mentioning: Gianni Rivera captained Milan for ten years and retired into the club vice-presidency in 1980, only to leave when Berlusconi took over the club. Baresi became captain three seasons after Rivera’s retirement, in 1982. Maldini took over from Baresi in 1997. Billy Costacurta has never, in spite of his quick tongue and professorial brain, come in between them. Rivera is now a parliamentarian in the left-wing coalition currently governing Italy. Baresi, voted Milan’s Player of the Century, coaches the club’s U-19 team, a job he took up after a six-month stint as Fulham’s director of football in 2002. Maldini is due to retire from the team in 2008.

3. Thanks to Vy, Risa, Neko & Curry for their help with vintage Milan photographs. This is for them, and for Sofie and her continued good advice. All mistakes are my own. Thank you for reading.

Milano, 1997.

It is the first time in thirteen years that the San Siro makes Paolo feel outright claustrophobic. He’s seen it this full before - he sneaked into the David Bowie concert in ’87 in spite of his father’s forbidding it - but he’s never been at the centre of such a gargantuan wave of attention in his life. It isn’t even directed at him. He huddles in the centre of a crush of teammates and club officials, as the shrieking, stamping largeness of the noise sloughs off the pillars and roars over the podium like it’s never done before, pounding under his feet like a bass line thumping straight up from the core of the earth. From beside him, Franco slips out to take the microphone from the president. Paolo watches him shrink a little as he breathes, away from it, and then square his shoulders, the way he always does once the football is over and the press conferences begin, and raise his head to the greying evening sky, the eighty thousand in the skyscraper seats who have come to bid him farewell. He clears his throat, faintly, over the PA system. The noise hums into a marginal softness.

“Thank you,” Franco says. “It’s time for the captain to say goodbye.”

He then hands the mic back to the president, who hasn’t had time to rearrange his face out of his expectant smile. He swings around once, slowly, hands raised to the crowd, and bows his head.

“What?” Paolo says, in the split second of dead silence. “What?”

Billy turns to answer him, but shuts his mouth as the applause cracks open above their heads, and shrugs.

“I thought you were giving a speech,” Billy says later, in the dressing room.

“I did,” Franco says, rummaging in his locker.

“A real speech,” says Billy. “With more than ten words in it.”

“I had one,” Franco says, smiling and matter-of-fact. He talks quickly, shortly, the way he always does to cover his nervousness at being unable to explain something. “I didn’t trust myself.”

Paolo, retying his shoelaces on a bench, looks up, and then straightens as Franco comes towards him. He actually gives it to him this time, presses it into his hand and closes his fingers over it.

“Before I forget,” Franco says. He looks at the stripes on Paolo’s jersey for a moment, then looks up and smiles.

“I,” Paolo says. “I.”

“Do well,” Franco says, and squeezes his shoulder.

“I will,” Paolo says faintly. He reaches out, impulsively, to hug the other man. Don't go, he thinks.

"Don't worry," he says.

"We should go back out,” Franco says, crushing Paolo's breath out of his ribs for a moment before pulling away. He jogs back out into the grey, smoggy dusk outside. Billy narrows his eyes at Paolo, winks quickly, and then hurries after Franco. Paolo follows him slowly to the entrance, and then looks down at his hands, at the armband twisting in his fingers. He turns back inside, straps it on, and tries to decide how it feels, if it feels. If he’s going to remember this moment for the rest of his life.

But he’s played football for fourteen years now, and he thinks to himself that in another fourteen years it won’t matter to anyone, not even to himself, whether he does or not. So he takes it off, stuffs it into his pocket, and goes out to join the rest of them. Night has fallen, and everything before him sharpens into a blinding brightness as the floodlights come on one by one.

*_*_*_*

Milano, 1985.

Your home away from home, a voice announces in Paolo’s head, when he comes to Milan. Alright, then. School is raucous and unruly, one long lunch-break filled with rising dust and sandwiches and boys shouting at each other on the yellowing field outside his classroom. Pass the ball, pass the ball, the fucking ball - oh, fuck. Give it here. Give! Let’s get out of here.

Home is quiet, held together by routine silences; the corners close in on minute, tacit understandings and conversations substituted perfectly by the clink of cutlery, sneakers or stilletoes tapping on the stairs, piano scales weaving in and out of the sound of murmured multiplication tables and the chief crops of Spain, and the evening news on the television. Milan is quiet, too, quiet like that.

Shit, the announcer in Paolo’s head says, a little irritably, when the thump of his school satchel on the bench and his shoes clattering to the floor are met with no answering voices. Not this. He looks around him, at the boys hanging up their shirts in the closets, the men whipping out the creases in the newspapers, all silent, the way deaf people are silent. He pulls his kit on. It whispers around his head, and he lets it shut the changing room out for a moment, suffocating agreeably in the light. It’s the proper jersey, the first team one with MALDINI on the back, instead of the nameless youth team one. No one on the Primavera dared crack the obvious joke when his father was within hearing distance, and a father like that is never really anywhere else. Another sort of silence, Paolo realises, and pulls the shirt over his head with vicious force.

He glances up, then, to see that someone is looking at him. Damn, Costacurta - Costacurta, like an obnoxious school senior, people (girls) all over him because he’s tall and handsome and talks, full of sarcasm and urbanity and his lucky bastard eighteen year old self. Not that he deigns to talk to Paolo, of course. Paolo looks at him, mouth open, trying to say something that isn’t I want to punch you, and then feels his neck prickle as Costacurta raises an eyebrow - raises an eyebrow - at him. At him. And then nods, and walks away, leaving the undefined, unspoken challenge hanging there, as though it were no more than a perfunctory greeting.

Welcome, then, Maldini, the announcer says. Welcome. Benvenuto a Milan.

His neck prickles again and he turns. The room is emptying now, the kitted-out players filing out like commuters at the subway station. There’s no one there but the captain, who is tying his bootlaces, and not looking at Paolo. He's a small man. Moves neat and alert, like a bird, but is granite when he's still. Paolo knows who he is, of course. Everybody knows il capitano. Juve have been asking ever since they came back up to Serie A, word has it, although you wouldn't know it to look at his face. Paolo is certain everyone in the world would be able to read him like a book if Juve ever called him. Excuse me, am I speaking with Maldini? Yes? Well, Maldini, I don't know if you know, but we've been watching you. We'd like to offer you a place. Yes, we know it's an honour. Yes, you're good enough for Juventus. Yes yes. For your own sake. Yes yes. We'll send a car around next Sunday.

All his life Paolo has listened to his coaches teach him football. They have all been his father’s teammates. Mister Liedholm always calls him ‘Paolo,’ careful to make him a little more than his last name (and maybe a little less). Paolo is so grateful for it that he does everything he is asked to twice over. The mister calls the captain ‘kid,’ although Franco Baresi is twenty-four and looks older than he is. The only thing he says to Paolo on the field that day is, “Trap it with your left before you shoot.”

Paolo is so dazed at the fact that the man talked to him that he does what he is asked, finds exactly the right timing for a pass to Wilkins, and feels, for a moment, like he’s learnt everything there is to know about football.

Before the year ends, Paolo drops out of school. The sum total of his education is now his attempt at unpacking tactics and unlocking attacks in the cool, moist shade of Milanello. He leaves the house before Cesare does and returns home long after Cesare has sat down to dinner. At work they ignore each other, except for when Paolo’s subway pass expires and he needs a ride home. (“You don't carry enough money for a bus ticket?” Cesare asks.) The emptiness ebbs into his afternoons. Milan is quiet, quiet like home. Quiet, in 1985, like the aftermath of a long struggle ending in inevitable failure. Quiet because Liedholm’s voice is soft and warm, threading through the team like the languid, mazy string of a pass. Quiet because Franco Baresi plays every minute on the field with a slow, considered viciousness and snuffs out his opponents’ moves in the second before they think of them, and doesn’t talk while he does this. Paolo stops playing the announcing game in his head and starts to work harder than he’s ever worked in his life before.

But gradually the silences begin to undo themselves, like a forward line whose patience doesn’t match up to your own. It never occurs to Paolo that he imagines things when they fall into place. It’s like a good game plan; you play it for long enough and the meanings suggest themselves to you in time. Example: Franco frowns, he comes to notice, for most things. He frowns when something annoys him, or worries him, or makes him want to smile in spite of himself, or when he wants to say Good game to his teammates but can’t because they’ve dropped points. He frowns when he pays attention to Paolo. When Paolo wants to say How am I doing, am I any good, I’m really not bad, am I?, he frowns back at Franco, who never takes notice. And because Franco leads by example, the rhythm they fall into is this one, where they smile only when they mean it and observe each other quietly, with attention, not needing to be told what to do. That steel core of silence lasts them through match after match, point after dropped point, through the trough of financial crises, of which Paolo reads only the most relevant details in the deepening creases around Franco’s mouth.

The mister throws him into the championship at left-back, one weekend in January. Franco frowns at that. He mutters, “Took you long enough,” when Paolo jogs, slowly, into position.

The first time the quiet is shattered, to Paolo’s ears, is when Berlusconi finally buys them out. Gianni Rivera, who negotiates with officials and players outside Milan and stands at the touchline clutching his hair whenever he’s down at the grounds, goes tearing through the club buildings in a rage. He throws his resignation letter down at the front desk and storms out of the gates.

“This club,” he shouts at the Mister before he leaves. “This club is not for charlatans!”

“You know, I love that boy,” the Mister tells Franco later. “But quite seriously, Franco, do you think he’s alright in the head?”

Franco puts his hand on the Mister’s shoulder and presses down. “I don’t know,” he says tightly. He frowns.

Three months later the new president announces a new coach. Paolo curls up into himself and ducks behind Franco, his fingers clutching involuntarily at Franco's shirt because they are, by then, at a stage where their silence, that mutual cessation of what will almost certainly be hostilities if they escape their throats, is the only thing they have left. He reacts needlessly, he realises. The only thing Franco says to Arrigo Sacchi, nodding once, is “Mister.”

*_*_*_*

Milano, 1986.

Sacchi destroys the quiet, simply by being everywhere, demanding to know everything, talking to everyone, shouting all the time, and shouting so loudly that it takes a while for Paolo to believe him, to believe that this is for real. He is a drill sergeant, bulldozing over them the way the workers reconstruct Milanello around them, making place to accommodate rose gardens and a new medical centre. Paolo has liked to think of himself, so far, as someone with an almost pious lack of animosity for anyone (even Costacurta, with whom, he persuades himself, he’s catching up soon). He hates Sacchi with a passion that hollows him out from the inside. He chivvies and hectors and governs them in a mad, Caesarist way that sets a nervy tension thrumming through the whole team. Only Franco doesn't seem to react. He lingers, as always, in the middle, waiting for his opposition, absorbing everything they throw at him, the way he absorbs the shock of this new everything. He reacts to the loudness, the hand-wringing, the mutinous current that makes even him tiptoe around the hotwired changing room, the castigation and the praise that Sacchi reserves for him, and him alone, on the training ground, by treating them with a stolid familiarity.

It drives Paolo mad. He starts, eventually, to wreak his havoc quietly, not having acquired the talent for rebellion that makes Billy stop and answer back when Sacchi gets short with him, earning himself plenty of harangues and an odd fondness from the coach. Paolo spits out everything he can give on the field and walks away with his head down and his lips trembling with the effort of keeping quiet. He talks himself into being an adult about it. Adults walk away from arguments. Adults have a life of their own, outside of home, outside of work, somewhere with different noises and colours and an honest demand for nothing but his wages and proof of age.

Sacchi finds him there, too.

He talks to Franco these days, in sporadic, convulsive bursts. He knows him better now, he knows how to decode the frowns; and he’s eighteen and desperate.

“So he asks me if I want to be a,” he says, when they’re alone in the little kitchenette (it doesn’t exist anymore) off the dorms, where players staying over the afternoon can go to get tea, toast, glucose biscuits, stuff like that. “A.” Franco is making coffee. It’s one of the things the team has come to rely on him for, for some reason. It is as demonstrative as he will be of his affection for them. Paolo takes a sip out of the cup he pushes towards him, gets his tongue scalded. “A playboy.”

“I see,” Franco says. Franco, to Paolo’s best knowledge, has never been to a nightclub at any point of time in his footballing career.

“He comes to Sardinia, okay,” Paolo says. “He follows me. To ask me that. To ask me that. I don’t even know what to. I mean. How did he know, anyway? How does he know everything? How does he know where I went on vacation when I didn’t tell him?”

“I told him,” Franco says.

Paolo inhales the steam off his espresso in silence at that, for a while.

“Should I not have?” Franco asks.

Paolo sighs, because he wants to slap his palms on the tabletop and say Why? and What on earth do you want from me now? and Do you want me to be like you? Is that what you want? Do you think I’m not already trying hard enough?”

“I don’t know,” he murmurs, and drinks his coffee.

Franco pats him on the back, and Paolo, for the first time, manages to read it with a clarity that is so astounding it almost knocks him forwards. He recollects, with the sort of shock to which adults are supposed to be immured, that it is not only Milan, who are on trial. That good enough for Juventus means also, at some level, good enough for Milan. AC Milan. Maldini’s Milan.

One day, a little later, he comes to the end of an exercise and turns to the touchline, to see Sacchi tensed forward, fist clenched over his mouth, watching him with that familiar mad gleam in his eye.

“My God,” Sacchi says, almost to himself. “Is there anything in this world you can’t do, Maldini?”

Paolo opens and closes his mouth, feels his heels sink into the mulchy grass. Franco passes by him, pushes him forward gently. “No,” he says to Sacchi, and winks at Paolo.

*_*_*_*

Pasadena, 1994.

When the last penalty of the World Cup final flies over the crossbar, Paolo learns, for the first time in his life, what it means to give beyond expectation or capacity and still fail. He knows, intellectually, what it means to lose and be treated unfairly. But this is justice, he tells himself, and is unable to cope with the fact that all their sweat and blood, all those weeks of watching Roby grimace when someone knocks him in training, Bergomi bloody-mindedly refuse to believe that he hasn’t earned himself this tournament, and Franco pull himself out of bed at five in the morning to wear his goddamn injury down by running on it - can bring them no further than this.

He turns himself around dazedly to try and protect them, all of them, even Sacchi, from whatever is starting to beat down on them in the pinpricks of the alien afternoon sunshine. The cameras are flashing across the touchline already. The scrutiny will be glass under their feet, and he wants to sweep it out of the way before someone steps on it.

Then, Franco breaks. It takes a moment for Paolo to register the sight of Sacchi comforting him. He has never seen Sacchi comfort anyone before. He has never seen Franco cry before. He has never seen anyone cry the way Franco cries, on that day, the heaving sobs reducing him to the reality of a smallness and fragility that no one these days believes him to possess.

It eases up the lump in Paolo's own throat a little. He has a practiced brilliance for following orders, so he puts it to use now. It doesn't matter that the orders themselves don't come: he’s done it for so long that he can make them up himself. He pushes everyone back to the dressing room, waits next to Sacchi, whose voice has never sounded more grating, and says things he isn’t thinking to the dictaphones. When he arrives into the showers he’s still checking things off in his head: say the right thing, don't say anything, leave the regret behind, don’t leave the medals, don’t cry, don't look, clean up after yourself, get everyone out.

He flops on the bench in the far corner of the changing room, instead, and lies down and closes his eyes. Then he opens them, hauls himself up and looks at Franco, sitting next to him, eyes dry and face smoothed out with blankness now.

“What?” he says, when he realises Franco is saying something.

“I said it's yours now,” Franco says. He’s holding the captain’s armband out.

No, it isn’t, Paolo wants to say. “Alright,” he says instead, and takes it. “Thanks.”

There is a dim understanding, eight years on, of the way things are with them. Paolo is older now, and he slips out of Franco’s shadow because he knows what he cannot become. He realises one day along the way that he has stopped growing, and that makes him realise that he will always be taller and faster now. His accent will always be different. His name and face will never be associated only with the number on his shirt. Franco’s imperiousness would be stiff-necked bullying in Paolo, his tranquility an act of petulance. Six feet of wax and wicker attempting to behave like a chit of steel; it would be absurd.

He has a hazy memory of going to the San Siro in 1979, for the last match of the season. His father took him because Milan needed a draw to win that scudetto. He doesn’t remember why there was crowd trouble, but there was, and the match got cancelled. Rivera then came on the field with a megaphone and shouted at the stadium, demanding that they behave themselves. The stadium quieted down as one; Milan won the match and the season, the first win in Paolo’s memory. Sometimes, when he imagines himself as captain, he makes himself be like that. It’s too much of a demand on his powers of presumption, though. So he finds the middle ground. He lets go a little. He loosens his limbs and makes himself smile at least as much as he frowns. It comes home, over that year that he wins the Champions’ League and loses the World Cup, that Franco is going to leave, and leave Paolo in his place, so he thinks fast, and begins to tide things over. He starts, in self-defence, to talk. He talks long and often. He talks to the press, he talks to his players, he talks to his coaches, he talks to his opposition. He talks to referees, officials, fans, and sponsors. He talks in Italian, Spanish, French and English. Sometimes he talks to the mirror. Not a club for charlatans, Rivera said when he left. Paolo, who decides to deal in bravado until he learns how to be brave, only allows himself to think that there are far worse fates.

*_*_*_*

They get a photograph taken, one summer afternoon at Milanello. As friends, now, as partners and equals (or almost, as a matter of time). The photographer recommends their standing close to each other, informal, smiling, jerseys untucked.

“I can’t put my arm around your shoulder,” Franco says, looking up at Paolo. “It’ll look like a chokehold.”

“I can’t put my arm around you,” Paolo says. “It’ll look like I’m trying to crush you.”

In the end they stand with their backs to each other, arms folded, post-firm and pillar-straight. “Great!” the photographer says. “Great shot, capitano! Smile. Smile!”

“He’s talking to you, Mr Supermodel,” Franco says over his shoulder.

“I don’t need to be reminded to smile,” Paolo says, on the verge of laughter. “Of course he isn’t talking to me.”

Franco doesn’t go away, after ‘97. When he walks into Milanello people still call him ‘capitano’ instead of ‘Mister.’ Even the new signings pick it up. Paolo finds it oddly relieving, possibly because, in time, they stop calling him ‘Paolo,’ the way they stopped calling him ‘Paolino’ a decade ago, and start calling him that as well. Everyone at Milan is a creature of habit.

He phones Franco regularly, during the times that they don’t see each other. They go to dinner now and then, where Paolo is still the one who has to persuade him to eat the odd dessert. He gets into the habit of keeping the conversation up. He calls Franco when his son says he wants to play football, and lets him laugh unmercifully at his paranoia. Sometimes, they talk about the old days.

“I really wanted to play for Juventus,” Paolo tells him one night in 2001, from a rooftop overlooking the city. The season is a full month away, which allows for the bottle of wine tipping recklessly over the ice bucket on their table. “When I was a child.”

“Good enough for that?” Franco says.

“I thought so, back then,” Paolo says. It makes him laugh.

“I,” Franco says. “I went for a trial with Inter, before I came to Milan. I failed it, though.”

Paolo covers his face with a hand and laughs more, à propos of nothing. One or two people turn around to look at them. Franco smiles, and kicks him under the table to make him behave himself.

*_*_*_*

Milano, 2007.

They let him alone while they troop in and out of the showers after the derby. He sprawls on the bench, dawdling, trying to make himself forget just how angry he is. He watches them as he’s watched them for years now, coming up against cocoons that he knows so well that he can almost see them - Ricky’s trembling anger, Andrea lingering on the field in his head, still directing a pass, Rino sulking, Ambro cleaning up after them, picking up bags and ties and complaints and pleas for reassurance and putting them in their places, neat and soft-voiced. The scene is so familiar that when Franco appears in the doorway he almost doesn’t notice.

They haven’t seen each other very often in the last five years, ever since Franco returned from Fulham in 2002 (“How is London?” Paolo had asked him over the phone. “I think you’d like it better than I do,” Franco had replied, not a little dryly). He looks at him now, greying hair, training shirt, same old unobtrusiveness, and wonders, not for the first time, if that is what it will be like for him. A coaching position, a chance to fade into the wallpaper.

It seems to have been easy for Franco; he smiles more often these days. Growing old sits well on him. He walks in, nodding here, shrugging there. Billy drops something and almost bounds across the room before Gila stops him with a question. Sandro walks right into him as he stalks out of the changing room, then chokes and tries to sink through the floor in a regressive fit of embarrassment when Franco says, “Good job,” and passes him by. He stops to talk with Mauro and Carlo as everyone filters out, one by one, and then lets Billy chew his ear off a little as he lingers a while.

“You look like you want to cry,” Billy says, finally looking at Paolo, because he won’t say Fuck and this is fucked up and what the fuck is this, Paolo. Paolo draws a leg up and starts to massage his ankle. He says, “I’ll call tomorrow,” to Billy, because he doesn’t want to say Fuck off and leave me alone.

“Cry?” Franco mutters, wandering into the room as Billy sweeps out. Someone has left a pile of loose sheaves of paper scattered on the floor, diagram after useless diagram (sketched out to stave off boredom, more than anything else) doodled and discarded. He sits down on the bench next to Paolo, begins to pick them up and leaf through them, putting them in order, one by one. He doesn’t say that was rubbish and you can’t make a headed clearance properly after all this time? and you can’t play football anymore? and you’re just back from a long trip to Japan, you’ve done well, it’s been a good year and it’s one match, Paolino, you think it matters? You think anyone’s going to remember in ten years?”

“Well, cry, if you want to,” he says instead. “You have things to cry about.”

And Paolo, Paolo doesn’t cry, because he doesn’t want to say I don’t want to do this and I don’t want to give this up and I should have given it up three years ago and I’m terrified and I’m tired. He slumps over himself, then stretches out and lies down flat along the bench. The movement disorients him briefly, as he looks up at Franco, frowning into his face. It feels like twenty years ago, just after someone has cracked into his nineteen year old ankles, just before Franco helps him up and glares him back into the game. It is the sort of love Paolo has learnt to give, over the years, although never that simply and that solidly.

It's time for the captain to say goodbye, the announcer rings in his ears, clear and resonant as the voice over the PA system ten years ago. Thank you.

"You're welcome," Franco says. "Let's go home now."

He waits for Paolo to shower and change. The groundsmen start turning the lights off as they leave, slicing the San Siro into darkness.

Notes:

1. This story is based on Milan’s recent history, but knocks an occasional fact over into fictionalization where convenient, mostly in the matter of timelines [Sacchi’s following Maldini to Sardinia, for example, happened before they started training]. Apologies for the liberties. This seems like a good time to disclaim the entire story as pure and complete fiction written for love rather than profit. It is. Read more about shadow boxes here. The title in no way correlates the fic with the play of the same name.

2. Three things whose incontrovertibility seems worth mentioning: Gianni Rivera captained Milan for ten years and retired into the club vice-presidency in 1980, only to leave when Berlusconi took over the club. Baresi became captain three seasons after Rivera’s retirement, in 1982. Maldini took over from Baresi in 1997. Billy Costacurta has never, in spite of his quick tongue and professorial brain, come in between them. Rivera is now a parliamentarian in the left-wing coalition currently governing Italy. Baresi, voted Milan’s Player of the Century, coaches the club’s U-19 team, a job he took up after a six-month stint as Fulham’s director of football in 2002. Maldini is due to retire from the team in 2008.

3. Thanks to Vy, Risa, Neko & Curry for their help with vintage Milan photographs. This is for them, and for Sofie and her continued good advice. All mistakes are my own. Thank you for reading.